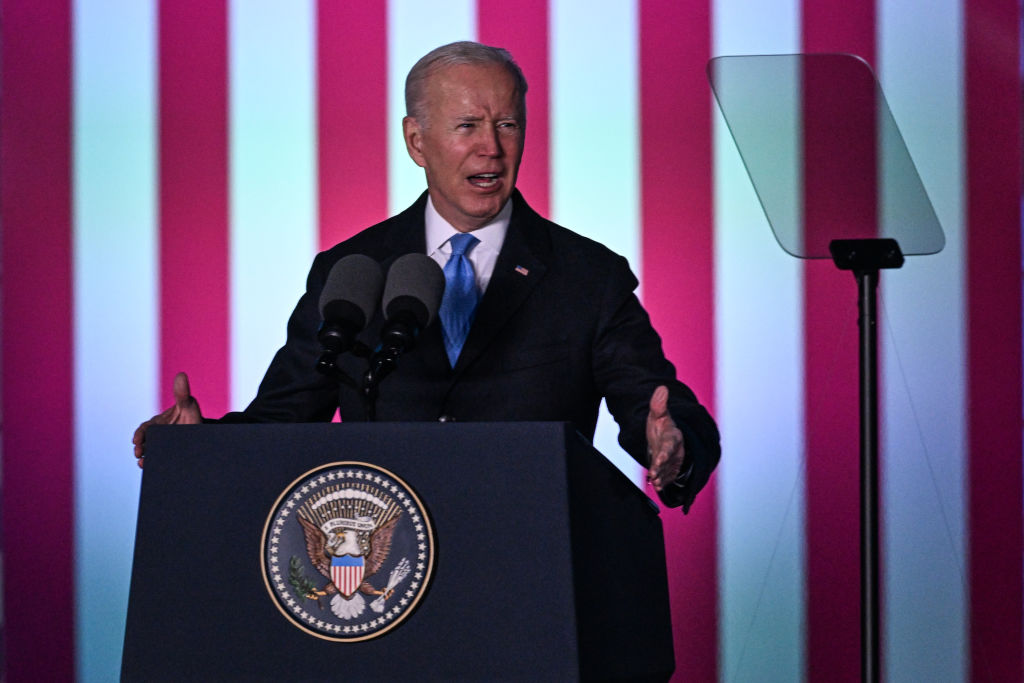

Joe Biden, by his own admission, is a man who sometimes goes off script. Whereas some presidents seek to bottle up their emotions and remain reserved for the cameras, Biden wears his emotions on his sleeves. The president proved that yet again during his visit to Poland over the weekend, where he let loose on Russian president Vladimir Putin at the conclusion of a speech: “For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power.”

Many in the West would privately agree with Biden’s assessment. If Putin was a cold, brutal and calculating autocrat before he launched a war of choice against Ukraine last month, he is now commonly depicted as a megalomaniac who has no compunction about invading a smaller neighbor, destroying cities with artillery and air strikes and killing a whole bunch of civilians in the process. For the tens of millions of Ukrainians who have been forced to flee their homes and the thousands of others who have experienced the death of family or close friends in the Russian bombardment, Biden’s words were a refreshing display of candor.

Unfortunately, those nine words were also a highly undisciplined — you could go as far as to say reckless — slip of the tongue that handed the Kremlin a meaty piece of propaganda to use at home as it continues to douse the Russian public with state-sponsored “alternative facts.”

Even more regrettable, however, is that Biden’s loose lips have the potential to reinforce the worst instincts of Putin, someone already liable to believing the US is sponsoring protest movements in Russia’s sphere-of-influence to weaken Moscow and perhaps convince the Russian public to push out Russia’s ruling class.

Americans and Europeans would scoff at this notion as another example of the Russian government’s extreme paranoia. Our opinions, though, are largely immaterial — what’s most important is if the Kremlin believes this line. Biden’s remarks have the potential to make a dire situation even more hopeless. Even Richard Haass, the so-called dean of the US foreign policy establishment, thinks so.

While the Biden administration won’t say so in public, it clearly believes the boss’s ad-lib about Putin was a mistake. Otherwise, the White House press office wouldn’t have released a clarification shortly after the president’s speech. Senior US officials spent Sunday on television trying to walk-back Biden’s comments. “Let me be clear and just state right off the the bat that the US does not have a policy of regime change toward Russia,” US ambassador to NATO Julianne Smith said on Fox News Sunday. Smith’s boss, secretary of state Antony Blinken, told reporters flat-out that “we [the US] do not have a strategy of regime change in Russia or anywhere else, for that matter.”

Some of Washington’s allies weren’t especially pleased with the rhetoric either. French president Emmanuel Macron, the only leader in the West who has kept an open-line of communication with Putin during the war, found it counterproductive. “I wouldn’t use this type of wording because I continue to hold discussions with President Putin,” Macron said on French television over the weekend. “We want to stop the war that Russia has launched in Ukraine without escalation — that’s the objective.”

Macron’s point is well taken. Ending the war in Ukraine as soon as possible is, or at least should be, the primary objective of the US and its European allies. The reason for this is straightforward: the longer the war churns on, the more likely Ukraine’s military (which has put up a stellar defense against a numerically superior Russian military) will begin to wear down. Russia’s problems on the battlefield notwithstanding, the country can opt for a war of attrition given the massive pool of reserves at its disposal. Ukraine doesn’t have the luxury of implementing a strategy of attrition. Indeed, despite all of the reports about Russia’s colossally large casualties (as many as 15,000, if NATO assessments are to be believed), Ukraine’s army is also experiencing losses in personnel and equipment, even if those losses aren’t reported on as extensively.

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky appears to recognize the asymmetry of military power on the ground. He remains adamant that NATO needs to send the Ukrainian military big-ticket weapons systems like tanks and combat aircraft, and he is delivering the message in barbed-laced interviews with major publications. Yet at the same time, Zelensky is increasingly open to the prospect of an end-of-war negotiation with Russia that could actually progress beyond the “here are my demands” stage. Before the war, the idea of Ukraine giving up on aspirations to join NATO was political kryptonite for a Ukrainian politician. Today, however, Zelensky is increasingly open to it as a means to ending the war and binding Moscow into a troop withdrawal from Ukrainian territory. Ukrainian and Russian officials are meeting in-person for the first time in weeks.

It’s too soon to say whether the talks result in anything substantive. If you were to place a bet, the safe call would be gambling against success. During his speech in Poland last week, Biden seemed to indicate that the war could drag on for months.

But this is all the more reason for Washington to support whatever opportunity for diplomacy happens to pop up, no matter how negligible the diplomacy may be. The US should be avoiding any rhetoric or policy action that makes a diplomatic breakthrough between Moscow and Kyiv less likely. This includes shooting off at the mouth, dreaming in public about what a post-Putin Russia would look like, or even hinting that regime change in Moscow is (or could be) a feasible US policy.

There are times when presidents are encouraged to speak their minds. But there are other times when it’s best for presidents to restrain themselves from openly saying what they are thinking. This was one of those times.