The University of St Andrews has been keen on American imports for some time. Americans make up 16 percent of undergraduates, by far a larger proportion than any other British higher education institution. The university, hungry for foreign money (international students pay £25,100 ($34,000) a year, compared to £9,250 ($12,500) a year for English, Welsh and Northern Irish students) sends recruiters to high schools in the States to woo potential students.

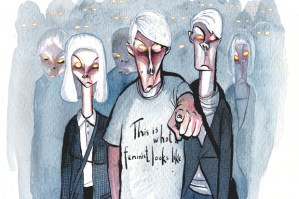

When I was at St Andrews a decade ago, I knew more Americans than Scots. Mostly, the university’s connections with the US have been good. Yet there is one American import St Andrews could do without: campus culture wars.

Saturday’s Times of London reports that St Andrews is no longer allowing students to matriculate unless they pass modules on sustainability, diversity, consent and good academic practice.

‘Does equality mean treating everyone the same?’ asks one question from the course. The answer the university is looking for is ‘no’, apparently. Those who respond ‘yes’ are told that, ‘in fact equality may mean treating people differently and in a way that is appropriate to their needs so that they have fair outcomes and equal opportunity.’

This kind of managerial, Human Resources gloop is very popular in America. First and second year students at MIT, for example, are required to take a Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Course (‘MIT is committed to providing you with an MIT experience that reflects the institutional commitment to provide a supportive community that allows our students to be their true selves’). And now the gloop has made it to northeast Fife.

A spokesman for St Andrews University told the Daily Mail that the Times story was inaccurate. The compulsory modules are not new, they have been ‘in place at St Andrews for several years’.

‘All of these modules were introduced at St Andrews in response to clearly expressed student demand. Our students pushed for the mandatory consent module, wrote the sustainability module, and were central members of the EDI (equality, diversity and inclusion) group which brought in the mandatory diversity module. The modules were developed to align with St Andrews’ strategic priorities (diversity, inclusion, social responsibility, good academic practice, and zero tolerance for GBV [gender-based violence]) and help develop skills and awareness valuable to life at university, and beyond.’

Whether these modules have been around for several years or not, they weren’t a feature when I was there. We called St Andrews ‘The Bubble’, and for good reason. The political and social trends of the outside world didn’t seem to matter much. I remember St Andrews as open-minded, intellectually inquisitive, and welcoming. Inclusive, in other words, and without the need for ‘strategic tactics’.

Campus controversies and culture warfare used to be rare. One year after I graduated, I remember hearing about an attempt to get Robin Thicke’s song ‘Blurred Lines’ banned from playlists in the students’ union because of its controversial lyrics. I also remember a student who managed to annoy animals’ rights types after he got drunk and ripped the head off a pigeon. That was about it.

It’s sad to see my alma mater fall into a managerial mindset. A university’s job should be to teach students how to think rather than what to think. What’s perhaps sadder is that the university’s spokesman is probably correct to say that these modules do, in one sense, prepare students for life beyond university.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.