The climate change summit in Glasgow will have one important part of the discussion missing: the role of nuclear power. It seems the British government is in no mood for a discussion with the nuclear industry — every one of its applications to exhibit at the COP26 summit has been rejected. That’s a shame, because there are plenty of myths to be addressed.

We could discuss the lessons from the plant at Fukushima, seriously harmed by a tsunami in March 2011. Sometime later, two of the reactors overheated, burst and released a small quantity of radioactive material into the environment.

At the time of this event, my wife Sandy and I were at our home in St Louis, Missouri. Our daily paper, the Wall Street Journal, had a detailed account of the tsunami. It also carried an editorial expressing the hope that the world’s press would not go overboard and falsely imply that 20,000 people had been killed because of the nuclear accident rather than the tsunami. The editor’s wisdom was ignored. Instead, there remains a deep-rooted fear concerning the safety of nuclear power.

Such power has been with us long enough to prove its safety. A study was recently done by the Journal of Cleaner Production: nuclear power is shown to be safer even than renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. The comparison is measured in terms of deaths and injuries per terawatt hour of power produced. (In the UK, we have produced at least 3,030 terawatt hours of power since nuclear installations were introduced in 1956.) The death rate is at least five times smaller than in the coal and oil industries for comparable power production.

In France, nuclear energy has been used on an even larger scale, generating more than 70 percent of the country’s electricity compared with our 18 percent. France is neither penniless nor dangerously radioactive. It is also more economically resilient to disruptions in the energy market than the UK. As the country is Europe’s largest energy exporter, Emmanuel Macron can threaten (as he recently did) to cut the UK off from the 10,000 GWh of French nuclear-generated electricity which is needed to power some one million homes.

Sandy and I had the privilege of being shown around two nuclear installations in France: the nuclear reprocessing plant at La Hague and the factory near Avignon where fuel rods were enriched with plutonium. I had with me a personal radiation monitor which let me see for myself that these places were safe to work in.

At La Hague I remember seeing a pond, the size of a large swimming pool, in which nuclear fuel from the reactors was placed to cool off. The uranium rods were highly radioactive and looking into the water I could see the bright glow of Cherenkov radiation shining from them. They looked deadly. I asked our guide: “What would happen if someone swam in the pool?”

“Nothing bad,” he replied. “The radiation level at the top of the pool is negligible. Check it with your monitor.”

This I did. The surface water would provide a warm, safe and enjoyable swim — although the glowing area near the fuel rods would be lethal.

We were also taken to an underground chamber beneath which 25 years of nuclear waste had been stored as glass in stainless steel containers. Again, it was safely buried, and my monitor showed an entirely safe radiation level.

To continue our present civilization, we need a steady supply of energy. We could easily have had it by now from safely controlled nuclear fission. I think fear has stopped us. And I mean fear of many kinds, ranging from the fear of looking foolish about our ignorance of nuclear physics, to the fear of nuclear war. Then there is the fear of losing wealth. If we go for nuclear as our source of power, what happens to the money we invested in coal and oil?

I lived and worked in London during World War Two. I saw and felt the consequences of living in a war zone. But when I visited Hiroshima, I shuddered when I saw pictures of those unfortunate humans in that city who were burnt to death in the glare of that first atomic bomb.

It is difficult to talk about fear without being personal. This introspective expression of my thoughts occurs because during World War One, my mother was a clerk at Middlesex town hall in London. Among her tasks was recording tribunals which judged the sincerity of conscientious objectors. She noted that few were given exemption from national service, but that frequently those exempted were Quakers. She decided when and if she had a son, he would become a Quaker.

So when my family moved to Brixton in 1926, I was enrolled aged six in the Quaker Sunday school. To my surprise and delight, the superintendent of the school was far more interested in cosmogony than in religion and his teachings fitted my emerging love of science. Best of all, he saw God as the still small voice within. That concept has been my touchstone ever since.

I was summoned to appear before a tribunal in early 1940. I was not then a Quaker, but became one soon after. I explained the reason for my pacifism and the three judges conferred to assess my honesty. After some discussion among themselves, they gave me an unconditional exemption from military service. I was fortunate to gain employment as a member of the scientific staff of the Medical Research Council at its institute in Hampstead.

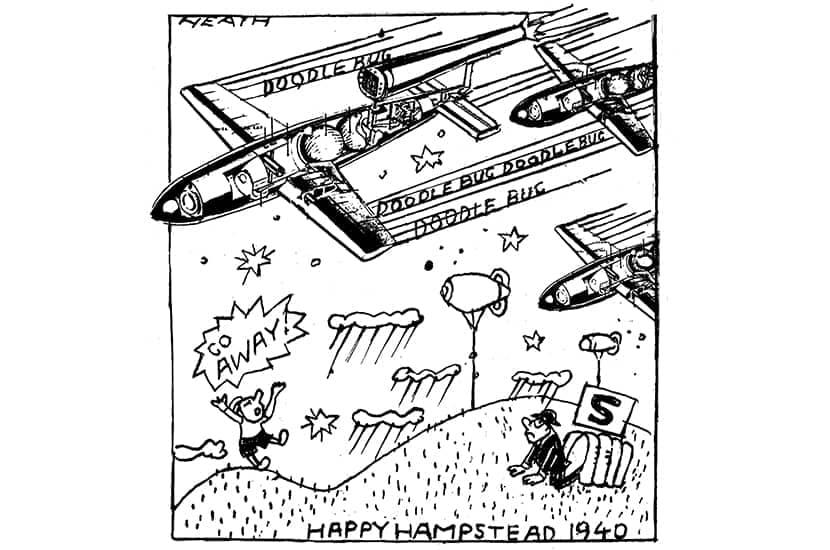

Not counting the Blitz, one of the worst periods of that war in terms of loss of British civilian life was during the attacks by the V-1 flying bomb. I can remember being woken up by the sound of rifle fire as well as bombs. It continued and we thought it must be an invasion. When the postman came, he said it was flying bombs, and there was nothing you could do about it. At this, my aunt Betty, who mistakenly thought that only planes with pilots could hurt her, cried out: ‘Thank God there is no one up there to drop the bombs on me!’ We all laughed, and the spell of fear was broken.

Today we need something like this to break the spell of nuclear fears. Just when V-1s were killing more of us Londoners in 1944 than any other weapon, a strange familiarity dispelled the fear. So it is with nuclear power. Every day, a huge nuclear reactor a million miles across swims across our sky. It will kill us all eventually, but for now we welcome the sunlight.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.