In the Point, Agnes Callard explains that she frequently assigns novels and poems in her philosophy classes. Why? Not because they provide her students with “personal ethical guidance,” and not because they help her students become more empathetic. She assigns them because they do what no other kind of text can do. They teach her students about evil:

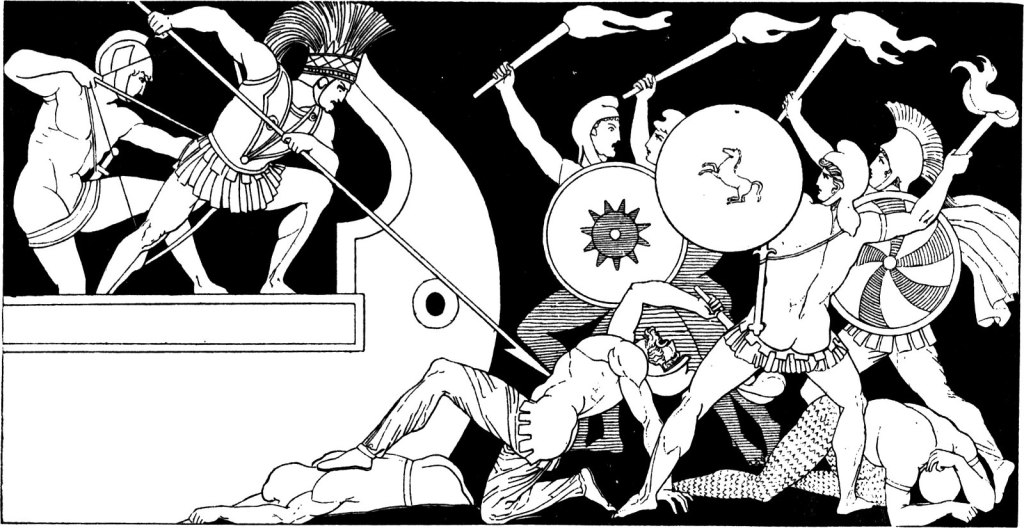

There are many complex theories about the nature and function of art; I am going to propose a very simple one. My simple theory is also broad: it applies to narrative fiction broadly conceived, from epic poems to Greek tragedies to Shakespearean comedies to short stories to movies. It also applies to most pop songs, many lyric poems and some—though far from most—paintings, photographs and sculptures. My theory is that art is for seeing evil.

I am using the word “evil” to encompass the whole range of negative human experience, from being wronged, to doing wrong, to sheer bad luck. “Evil” in this sense includes: hunger, fear, injury, pain, anxiety, injustice, loss, catastrophe, misunderstanding, failure, betrayal, cruelty, boredom, frustration, loneliness, despair, downfall, annihilation. This list of evils is also a list of the essential ingredients of narrative fiction.

I can name many works of fiction in which barely anything good happens (Alasdair Gray’s Lanark, José Saramago’s Blindness, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Jon Fosse’s Melancholy are recent reads that spring to mind), but I can’t imagine a novel in which barely anything bad happens. Even children’s stories tend to be structured around mishaps and troubles. What we laugh at, in comedy, is usually some form of misfortune. Few movies hold a viewer on the edge of their seat in the way that thrillers and horror movies do: fear and anxiety evidently have their appeal. Greek and Shakespearean tragedy would rank high on any list of great works of literature, which is consonant with the fact that what is meaningful and memorable in a novel tends to be a moment of great loss, suffering or humiliation.

She goes on to explain why art is the medium for representing evil, but she also responds to the objection that art is only about representing evil. After all, what about the many scenes of moral goodness in Pride and Prejudice? What about William Wordsworth’s pastoral “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”? What about John Constable’s The Hay Wain?

Callard doesn’t deny that works like these contains positive scenes or characters. But she does argue, in a brief discussion of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, that those positive scenes or characters are secondary to the work as a whole:

The positive has a secondary and derivative place in fiction, just as the negative has a secondary and derivative place in life. In life, we are looking for all the various ways to make our marriages succeed; in fiction, we are fascinated to observe all the possible ways a marriage could fail. That is the insight behind Tolstoy’s opening sentence: it is true of fiction, even if it is not true of life.

Callard is on to something, but her case would have been helped if she picked a work like Pride and Prejudice where the evil in the novel seems to be very much there to illustrate the good, not the other way around, which is what Callard seems to be saying.

In other news

Speaking of stories, Timothy Farrington reviews a new translation of Aristotle’s Poetics by Philip Freeman. The translation, written for “the civilian raconteur,” is given the contemporary title How to Tell a Story: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Storytelling for Writers and Readers. Freeman’s translation laudably tries to lighten Aristotle’s heavy prose, but he isn’t always successful:

Aristotle’s intriguing claim that using metaphor well “is a sign of genius” (euphuias semeion), for example, is redundantly rendered as “It is quite simply a natural talent for those who have it.” This “if you got it, you got it” shrug is hardly a minor point, because Aristotle also holds that the most important element of style is to “be good at metaphor.” One stimulating way to think about the Poetics, then, is as not only a book of rules but an early entry in an age-old argument: Can writing be taught at all?

Are imaginary numbers real? Yes, Karmela Padavic-Callaghan argues in Aeon, because they are necessary:

In their simplest mathematical formulation, imaginary numbers are square roots of negative numbers. This definition immediately leads to questioning their physical relevance: if it takes us an extra step to work out what negative numbers mean in the real world, how could we possibly visualise something that stays negative when multiplied by itself? Consider, for example, the number +4. It can be obtained by squaring either 2 or its negative counterpart -2. How could -4 ever be a square when 2 and -2 were both already determined to produce 4 when squared? Imaginary numbers offer a resolution by introducing the so-called imaginary unit i, which is the square root of -1. Now, -4 is the square of 2i or -2i, emulating the properties of +4. In this way, imaginary numbers are like a mirror image of real numbers: attaching i to any real number allows it to produce a square exactly the opposite of the one it was generating before.

Rafael Schächter, a conductor imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp, taught 150 fellow prisoners to perform the Verdi Requiem by rote. Jacob Heilbrunn didn’t believe it when he heard of it, but it turns out it’s true.

James Matthew Wilson reviews W.H. Auden’s Complete Poems:

In his poetry above all, Auden reckoned with the great historical forces of his age and struggled — genuinely — to arrive at an accurate understanding of and a moral response to them. These new volumes make that struggle visible to us in a way that it has not been since the days of Auden’s first readers. The Collected Poems published during Auden’s lifetime included only the poems that he wished to preserve, often in revised form and in roughly chronological order; this minimized and concealed the growth of and debate within the poet’s mind. In these new volumes, Mendelson has reconstituted the original collections of poems in, more or less, their earliest published forms. We see the moral debate play out, volume by volume.

And Thomas Jones reviews the seventh volume of the Complete Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley, which “is both a comprehensive scholarly variorum edition and a handsome and accessible reading text” of the poems:

As well as The Triumph of Life, its discarded openings, rejected passages and lyric fragments from the manuscript, Crook’s volume contains what’s left of Posthumous Poems once “the poems that PBS had released during his lifetim” and translations have been excluded: these appear (or will appear) in other volumes. “Julian and Maddalo”, “The Witch of Atlas”, “Letter to Maria Gisborne” and “Mont Blanc” are out; “An Unfinished Drama”, “Charles the First” and around half the shorter lyrics are in. But the main event is The Triumph of Life.

Scott Yenor reviews Brian Patrick Mitchell’s Origen’s Revenge: The Greek and Hebrew Roots of Christian Thinking on Male and Female:

Mitchell shows how the Christian tradition supports multiple views of what it means to be male and female. The Greek view, informed through gnostic teachings, as Mitchell presents them, conceives of sex as an accident to be worn away through a perfected or sanctified life, while the Hebrew view finds human life sexed to its core. After establishing that, Origen’s Revenge stages a battle of the books among early church theologians to show how the Hebrew-Christian view captures Christian truth more than the Greek view does.

In the Washington Examiner, I write about the art of climate activism:

Environmental activism used to take real work. Joseph Beuys, for example, planted 7,000 oak trees over five years (he finished in 1982) in Kassel, Germany, to advocate greener cities across Germany. The Hungarian-American artist Agnes Denes planted two acres of wheat by hand in a landfill in New York City in the early 1980s to “call attention to our misplaced priorities and deteriorating human values” — that is, America’s preoccupation with making money rather than focusing on “world hunger and ecological concerns.” Even Andrea Polli’s 2010 installation Particle Falls, which projected a waterfall of light on the side of a building to represent pollution in real time visually, required her and her team to connect the measurements of an air monitor to lasers. Now, all you need is a phone and spurious moral reasoning.