New York

I received a letter from a long-time Spectator reader, James Hackett, enquiring about books I am reading. It is not often that I get letters that delight me, as this one did. It is a far cry from the readers’ letters you see in newspapers and magazines in the United States. Lots of them seem sanctimonious, holier than thou; others, I suspect, are written by the glossy magazines themselves promoting their own celebrity culture worship.

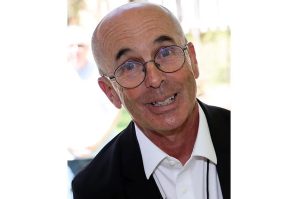

James Hackett is an American gent whom I’ve never met, and I hope I don’t disappoint with my choices. The last time I read novels was literally some 50 years ago. I stopped reading them after I’d made my way through the Russians, all of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, O’Hara, Shaw, Jones, Mailer, Maugham, Greene, Orwell and Waugh, among others of the period. Why did I not continue reading fiction? That’s an easy one. Because authors began to write very, very, very long books containing millions of words that didn’t exactly ever get to the point, instead describing weird objects in improbable situations. The style was even worse than magic realism. To someone like me, used to clear and precise prose, this defeated the purpose of reading. What I like is beautiful, descriptive prose about interesting people. Modernity was gimmicky. I remember Truman Capote’s description of On the Road: ‘That’s not writing, that’s typing.’ But I liked Kerouac, just as I liked the writing of the truly horrible man that was Capote. (The maligned Answered Prayers is a gem.)

So, Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon, Martin Amis and Salman Rushdie are not for me, and I am rather proud to say that I’ve never read more than a chapter of any of their books before giving up. It might not make sense, but I don’t believe a word they write, because fiction has to be believable. I trusted Dick Diver and Nicole, Jake Barnes and Brett Ashley, and Stephen Rojack and Winston Smith, not to mention Raskolnikov, Prince Andrei and Larry Darrell. And what about Christian Diestl in The Young Lions, the perfect soldier until disillusionment sets in. From what I’ve read about him, Evelyn Waugh was a horror — snobbish and a bully — yet reading his books, even at their satirical heights, I believe every word because I have met English people just like those he describes in Vile Bodies.

I met Vladimir Nabokov in Gstaad towards the end of his life, and even if he had never written another word I would have bowed low to him for the description of a young woman in one of his short stories. The author notices a drop of sweat slowly running down the beautiful girl’s leg. Old Vlad was a lepidopterist and detail was his forte, but my taste runs to mood, Fitzgerald’s forte.

Once the novel became unreadable for me, I turned to biography and history and they have served me well. I’ll get to that in a moment, but first, here’s how I rediscovered fiction. It was a couple of years ago and I was in the Cotswolds for a ball Prince and Princess Pavlos of Greece were giving on their Oxfordshire estate. A friend had asked Lord Bamford, whose house Daylesford is among the most beautiful in England, if he could put the poor little Greek boy up for a night.

As it happened, I returned at around 6 a.m. and my host was up saying goodbye to the Queen of the Netherlands who was also staying. For reasons that I will not go into, I felt awfully chatty and engaged my host — who happens to be among the nicest and most polite people — in a one-sided conversation about the Wehrmacht. His answer to my rudeness was to send me two books by Philip Kerr, Prussian Blue and Metropolis. Bernie Gunther, the hero, is different from the private eyes created by other greats such as Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. Not as hardboiled, I suppose. The only fiction I’ve read recently has been Philip Kerr thrillers. And the only thing to say is thank you, Anthony, and sorry about the soliloquy.

[special_offer]

As we live in a time where books are out of style and ghastly contraptions are all the rage, what keeps one sane is reading history and biography. I enjoyed Our Man, which is about the horror that was Richard Holbrooke; his terrible personal habits and self-promotion, his treacherous nature but undeniable talents in seeing through the fog of disastrous American foreign policies. The biography of Anthony Powell by Hilary Spurling has also kept me happy during lock-up. Left Bank and Lost Girls of Paris were two books that got me all riled up and reminded me of my youth in Paris and London, and of course the two-volume biography of Clare Boothe Luce by Sylvia Morris was unputdownable. (I had withdrawal symptoms after I’d finished it.)

And when I got bored, I turned to war books. James Holland’s The War in the West is magnificent, as is film man Sam Fuller’s A Third Face. I spent four days in the company of James Holland in Normandy a couple of years ago, thanks to my friend Peter Livanos’s invitation to visit the battlefields and learn all there is to know. From the allied side, that is. I had too much respect for James to argue, but had the opposition enjoyed the total air cover the allies did, they would still be fishing them out of the water today.

Keep reading and throw away the machines. And imagine how wonderful the world would be without the internet, Twitter, Google and the rest of the garbage.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.