This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

Batavia, New York

Shrouded in legend, Black Mountain College was an experimental school outside Asheville, North Carolina. For almost a quarter century (1933-57) it incubated, nurtured and disgorged the holy fools, ragged prophets and pretentious frauds of the American avant-garde and the (in some cases reactionary) counterculture: John Cage, Paul Goodman, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning and Buckminster Fuller, to name a few.

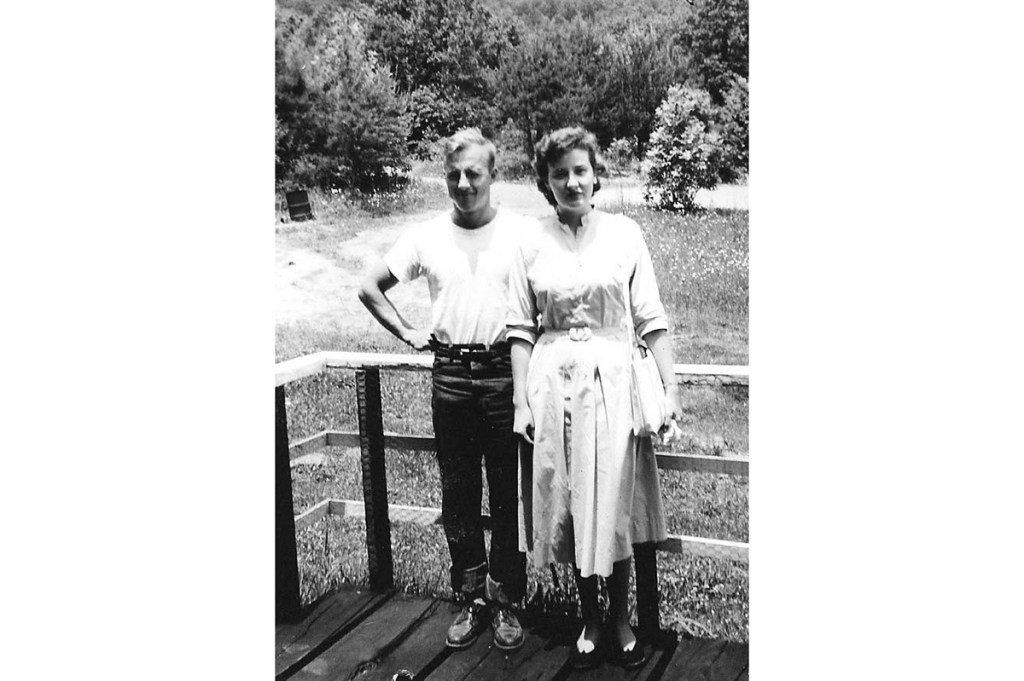

Yet for my money, the most remarkable couple to pass through Black Mountain were Bill and Martha (Rittenhouse) Treichler, two farm kids, the former an Iowan, the latter a daughter of Maryland, who met and fell in love at Black Mountain during the 1948-49 school year.

You wanna talk Americana? Bill’s mother had attended fifth grade with the ‘American Gothic’ painter Grant Wood. Martha was a 4-H all-star who designed and sewed her own clothes. For the six decades after they left Black Mountain until Bill’s death in 2008, they built their own homes from salvaged bricks and native lumber, grew their own food, milled their own flour, raised their own livestock and brought up five children, whom they read to sleep at night from the works of Walter Scott and Trollope. They also published the Crooked Lake Review, a fine journal of Upstate New York culture.

Mildred Loomis, the ‘grandmother of the counterculture’, praised the Treichlers as the compleat homesteading family in her 1982 volume Alternative Americas. In 2006 they even gave me one of the few satisfying voting-booth experiences of my life when I cast a ballot for the Treichlers’ daughter Rachel, the Green candidate for attorney general of New York.

The anarchist spirit of Black Mountain was accompanied by a certain untidiness: Bill Treichler, upon arriving, was ‘dismayed by the unkempt campus overgrown with high grass and weeds’, recalls Martha. When Bill complained to his parents, they sensibly suggested ‘that he stay and cut the grass’. He did. (John Cage sure wasn’t going to do it. Nor was Bob Rauschenberg, though he did lend Martha his sewing machine.)

The place left a deep mark on the Treichlers, who combined poetical imaginations with hoe-and-axe practicality to a Wendell Berryan degree. It also gave Martha a mentor and even collaborator: the whalelike 6ft 8in poet Charles Olson, best known for harpooning Herman Melville.

The one sour note in Martha’s reminiscences — which we shall sweeten — concerns Edward Dahlberg, the novelist and critic who taught briefly at Black Mountain before decamping just weeks into his stay because the city boy found the students ‘insolent’ and the Carolina foliage ‘homicidal’, citing its ‘savage, serpentine trees and leaves’. Dahlberg had been a member of the Communist Party USA, so he was no stranger to mendacity, and one fib he told of his miserable sojourn at Black Mountain slighted Martha. Happily, it’s not too late to set the record straight.

In Martin Duberman’s history Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (1972), we read: ‘A girl named Martha Rittenhouse said she’d read Proust over the summer. “What Proust?” Dahlberg demanded. “All of it,” Martha answered. “Why?” Dahlberg asked. “Because it was there,” said mountain-minded Martha.’

Not true, says Martha today: ‘I did not say what Dahlberg attributed to me. I had read some of Proust in a French literature course at my previous college, Bridgewater College, and thought him interesting. I was working as a live-in babysitter and nanny for some rich folks, to save money for college, and after my charges were in bed, I had hours to fill. I read Proust. At Black Mountain I felt Dahlberg was making fun of me for reading the seven novels of Proust in nine months. I resented this.’

Duberman continues: ‘Dahlberg later got even with her; when she gave a disapproving oral report on Madame Bovary, regretting in passing that Emma had married “for reasons of carnal lust”, Dahlberg, ignoring the garbled literary interpretation, shot back at her, “My dear Miss Rittenhouse, for what reasons do you intend to marry?”’

Another lie. Says Martha: ‘As we discussed the book in class, I commented that I did not think Flaubert treated his character, Dr Bovary, fairly. He gives him a club foot, and, I thought at the time, was unjustifiably demeaning to this character. I did not complain that Emma married “for reasons of carnal lust” and I do not remember Dahlberg’s saying, “My dear Miss Rittenhouse, for what reasons do you intend to marry?” In my opinion, Dahlberg did not treat his students with respect, and as I remember it, I was not the only one who felt this way.’

OK, record corrected.

Martha, who turned 91 in February, is still writing, giving readings, canning tomatoes, corn, green beans and cabbage, and making cider. In 2020, the Beat-flavored FootHills Publishing will bring out Hanging on a Limb, her seventh volume of poetry in the past decade. The title piece goes:

‘Year by year

the limb sags a little;

‘year by year

my hands slip a little;

‘year by year

my arms tire;

‘but the view is spectacular.’

This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.