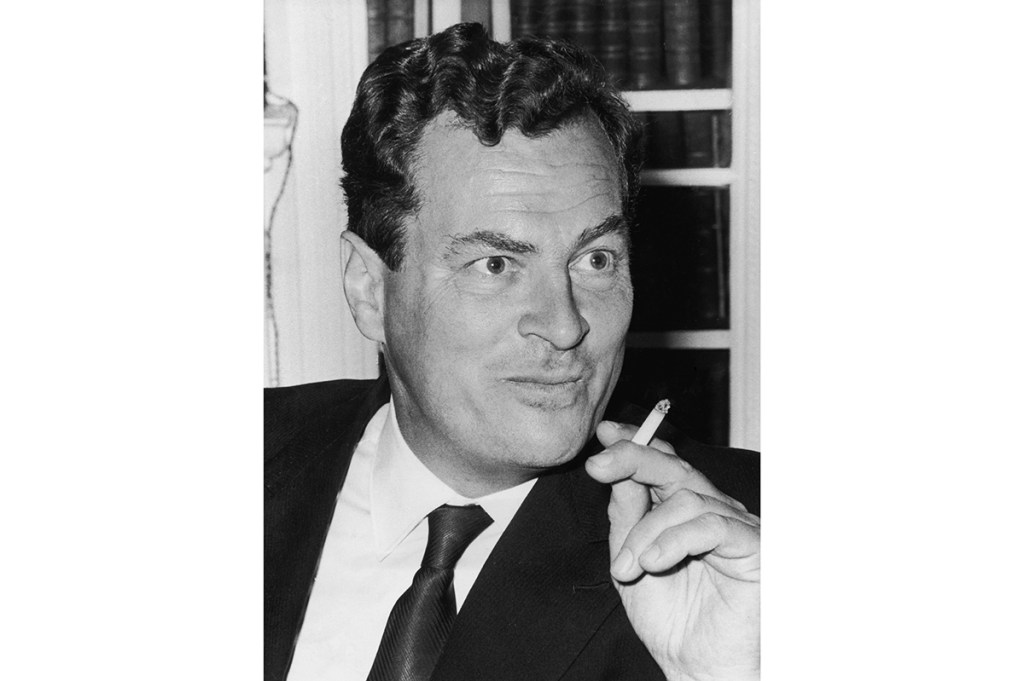

Before he was a celebrated travel writer, Patrick Leigh Fermor (who died in 2011 at 96) was a celebrated special operations soldier. In February 1944 he commanded a raid to kidnap General Heinrich Kreipe, the newly installed German commander of Crete, and take him to Egypt. Leigh Fermor, his fellow officer William Stanley Moss and three members of the Cretan resistance commandeered the general in his car and made a daring trek across the island pursued by the German occupiers.

They spent one chilly night on the slopes of Mount Ida. At dawn, with the sunlight splashing against the face of the mountain, Fermor overheard his captive reciting the beginning of Horace’s Ode 1:9, ‘Vides ut alta stet nive candidum Soracte…’: ‘Do you see how gleaming Soracte stands there swaddled in deep snow…’ Leigh Fermor knew the poem and picked up where the General stopped, reciting the rest of ode in Latin. ‘For a long moment,” he recalled later, ‘the war had ceased to exist. We had both drunk at the same fountains long before; and things were different between us for the rest of our time together.’

As autumn deepens and winter is nigh, I often think of that story and the poem it features. I have always thought it a lovely Christmas dinner poem, for after, invoking the majesty of the mountain in winter, Horace goes on to urge us to pile logs upon the fire in the hearth and ‘benignius deprome quadrimum Sabina… merum diota’: ‘pour out more lavishly the four-year-old wine from its two-handled Sabine jug’.

What do you suppose that unwatered wine (merum) was like? Between us, it probably couldn’t hold a candle to the wines available today. But I like to imagine that it was like some expansive Cabernet or sumptuously elegant Pinot Noir, something that could stand up well to and complement the tenderloin or Beef Wellington you are planning for Christmas dinner.

Let me suggest a Pinot Noir from Joe Wagner, who owns four vineyards along the California coast. He calls his wines Belle Glos (pronounced ‘Bell Gloss’) after his grandmother, a co-founder of the famous Caymus Vineyards in Napa.

Caymus makes one of the premier Cabs in California — maybe try one on New Year’s Eve, before the Champagne — and Joe Wagner grew up as a sort of vine rat, helping to tend the vineyard. He ventured out on his own in 2001. His most recent vineyard, on the site of an old dairy farm in Sonoma, is called Dairyman.

It nestles in the cool, foggy Russian River Valley and produces a luscious Pinot Noir that lists for $55, but which you can probably snag from an understanding vendor for $48-$49.

Nietzsche famously remarked that ‘What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.’ Like many things the old philologist said, that is not true, at least not of people. It sounds good, though, and it does have a certain truth when applied to vines. To a certain point, the more they are stressed, the more concentrated the flavor of the grapes. This is why poor soil tends to make for good-tasting wine. ‘In Dairyman,’ Wagner’s literature notes, ‘each vine has been trained up on a vertical shoot position (VSP) trellis, which both limits the growth and opens up the typically congested fruit zone. The combination of low-vigor rootstock and alluvial soil stress the vines, while the cool, coastal climate creates a long growing season that brings about small, concentrated, and flavorful berries.’

Wagner seals his bottles with a distinctive scarf of burgundy-colored, wax-like plastic over the cork and partway down one side of the bottle. A small knob attached to a sturdy string protrudes from underneath the lip and one removes the top of the seal by pulling — hard — on the knob.

The 2018 vintage, aged nine months in French oak, was released in 2019. It was a warm growing season with an average temperature of 77.6°, which probably helps account for the wine’s friendly fruit forwardness. Wagner describes the 2018 Dairyman as a ‘tremendously complex and broad-shouldered wine [that] finishes with grace’. This is true. Oenophiles are always discovering (when they are not simply imputing) all manner of strange tastes and scents in wine. But Dairyman really is reminiscent of some old standbys in the vocabulary of wine speak: there are hints of pipe-tobacco, fresh leather and vanilla in the finish.

Try it and you will see, or taste, for yourself. The wine is full and lingering in the mouth, beautifully structured and somehow confidential. At a robust 14.5 percent alcohol, it is also hearty: just right for that beef you prepared and are planning to enjoy in front of the fire while reciting Horace among friends, with or without a kidnapped German general.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2020 US edition.