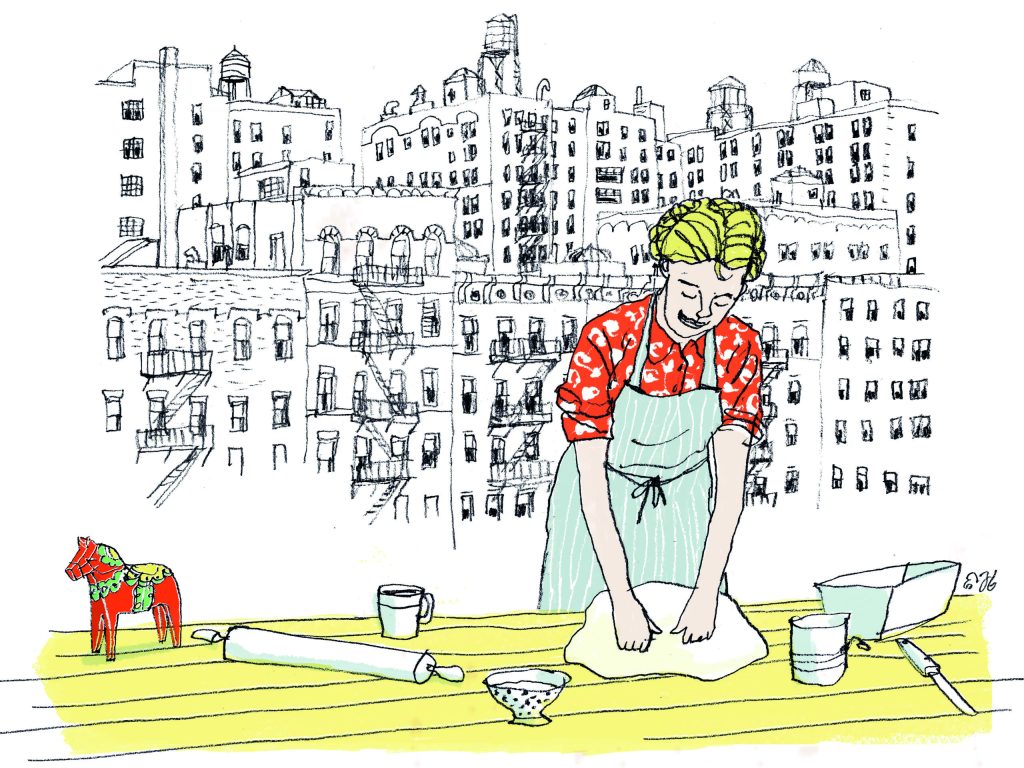

I don’t remember my grandmother, Anna Olson Nelson (Nelsie to her grandchildren), ever measuring out anything for her divine Swedish bread. The recipes must have been kept under the thick, blonde braid that she piled expertly on top of her head. What I do recall, as if it were yesterday, is helping Nelsie bake fläta and limpa every other Sunday in her small kitchen. The heavenly smells of cardamom and fennel wafted throughout her apartment while she tried to improve my Swedish.

My mother, Mimi, often spoke Swedish to me and my sister, Chris, when we were babies and my father was with the Office of War Information as a correspondent in China, Burma and India during World War Two. Nelsie was our ‘Swedish nanny’. Now, I wish the family’s version of Berlitz had continued after my father came home in 1945. Swenglish was the unsatisfactory result — at 77, I still speak baby Swedish. But I am fluent when I communicate the joys and need for baking Nelsie’s Swedish breads.

Nelsie emigrated from Helsingborg, at the age of 16, with her older brothers, Otto and Gus. The siblings sailed to America in the early 1900s along with many other northern Europeans, to seek, and even make, their fortunes. They established themselves in ‘Swedentown’, in the upper 90s on Manhattan’s Second Avenue.

My great-grandfather was the head gardener at the King of Sweden’s summer palace, Sofiero, known for its spectacular rhododendrons. Nelsie once told me that she was often homesick when she was in her twenties. She could have stayed in Sweden and baked for the royal family, she said. I never asked why she didn’t.

Why her brothers left was also a mystery; maybe the brothers just had Norse adventure in their Viking blood. Nelsie found a job as a cook with a wealthy Upper East Side family. Her brothers opened a candy shop on Second Avenue and made their fortunes before eventually retiring to Florida.

When my husband Richard and I lived in Lausanne, Switzerland, I baked fläta and limpa for our annual glögg party, celebrating Christmas the Swedish way: loaves of fläta as gifts for friends, to toast and dip into coffee over the holidays; loaves of limpa, served with gravadlax, tiny all spice-laced meatballs, five types of herring and cumin cheese washed down by icy aquavit, served on a Swiss version of a groaning board.

When we moved to Brussels, I carried on the Swedish tradition. It looked like the smörgåsbord might end, however, when Richard quit his job mid-career to tempt fate. We moved to our summer house on Cape Cod, Richard sent out his résumé, and our teenage children, Keith, Annabelle and Lucy, who were OK with horrid American bread during summers growing up, suddenly were shocked that they couldn’t have baguettes, croissants and pains au chocolat. They begged their unemployed father to bake, at least, baguettes. Richard’s attempt was an utter failure, which any amateur baker who has tried to make a decent baguette with an ordinary oven can appreciate.

Mimi came to the rescue, reminding Richard of Anna’s fläta and limpa and about the jars of fennel and cardamom that were tucked away. It didn’t take long for Richard to start baking. Nor did it take long for George Nolin, our delightful summer neighbor, to get a whiff of the cardamom and fennel and implore Richard to teach him to bake Nelsie’s bread. George, a soon-to-be-retired DC lawyer with a knack for sniffing out business ventures, even suggested that they go into the baking biz. ‘Beats becoming commercial fishermen,’ he told Richard over bottles of beer on the Mill Pond one hot August afternoon.

The bakery never became more than an excuse for a cold afternoon beer. Richard was called to Manhattan; George saw an opportunity to invest in short-term storage. From time to time, Richard would bring out his stash of cardamom and fennel seeds from the souks of Beirut, Bahrain and beyond, and bake Anna’s bread.

Our daughter Annabelle, now a mother of two in Burgundy, is keeping up the tradition. I can almost hear Anna complimenting her great-granddaughter: ‘Dessa är underbara, Annabelle!’ I’ve also taken up baking Nelsie’s breads again as we wait out the challenges of 2021. There’s something cathartic about needing to knead bread.

Fläta (Braided Swedish Sweet Bread)

For four loaves, baked at 375 degrees for 25 to 30 mins

Four 9-inch lightly greased non-stick loaf pans

4 packages active dry yeast

½ cup warm water

1 cup butter

1 ½ cups milk

1 tsp salt

1 cup sugar

2 eggs

1 cup raisins

10 tsp freshly ground cardamom seeds

7 cups flour (bread & pastry flour or all-purpose flour. Most of the seven cups get mixed in, leaving a little for kneading)

For baking: 1 egg, beaten;

Swedish pearl sugar or granulated sugar

Dissolve the yeast in ½ cup warm water. Melt the butter in a saucepan and add the milk. Pour both into a large mixing bowl. Stir in the salt, sugar, eggs, cardamom and raisins. Mix with the flour until the dough is smooth and elastic, adding more flour gradually.

Turn out the dough onto a lightly floured working surface; knead and form into a ball. Sprinkle the ball of dough with a small amount of flour and put back into clean, greased bowl, turning to be sure all sides are greased.

Rise 1: Cover the bowl with a damp clean tea towel and let rise in a warm place until doubled in bulk, approximately one hour. (A slightly warmed-up oven is a good place.)

Punch down dough and turn onto lightly floured baking board. Knead until smooth, adding more flour as necessary. Divide dough into four parts to make four braids. Cut each portion into three equal parts. Roll and shape each of the parts into strands 12 inches long. Braid. (If braiding dough is new to you, directions for braiding fläta are easily found online.) Place each of the four braided loaves in lightly greased nine-inch non-stick baking tins.

Rise 2: Cover and let rise until doubled in bulk, about 45 minutes.

Brush with beaten egg. Sprinkle with sugar. Bake in a 375°F oven for 25 to 30 minutes. Turn out and let cool on a rack.

Limpa (Sweet Rye Bread)

For four loaves, baked at 350°F for 35 to 40 mins

Four 9-inch lightly greased non-stick loaf pans

3 cups beer

4 tbsp freshly ground fennel seeds

2 tbsp white vinegar

½ cup molasses

½ cup dark corn syrup

4 tsp salt

4 packages dry yeast

4 tbsp softened butter

8 cups fine sifted rye flour

3 ½ to 4 cups sifted all-purpose flour

Heat beer to lukewarm.

Combine in large bowl with fennel seeds, vinegar, molasses, corn syrup and salt. Sprinkle yeast into lukewarm liquid and stir until dissolved. Beat in butter. Stir in rye flour and three cups all-purpose flour a little at a time; mix well. Use some of the remaining all-purpose flour to sprinkle on working surface. Turn dough onto working surface and knead with floured hands until smooth and elastic and no longer sticky. Place dough in a greased bowl and turn to grease on all sides. Cover and let rise in warm place until doubled in bulk, about 1 ¾ to two hours. Punch down, pull edges toward center and turn dough in bowl. Let rise again until almost doubled in bulk, about 45 minutes.

Turn dough out onto floured work-ing surface and divide into four portions. Knead for two minutes and shape each portion of dough into a loaf. Place in greased baking dishes and let rise again until doubled in bulk, about 50 minutes. Bake in a 350°F oven for about 35 to 40 minutes.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.