Serifos

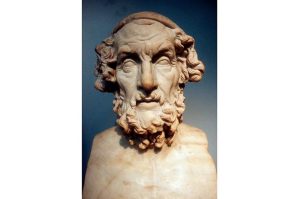

There’s no high life here, only family life, so I’ve been hitting the books about great Greeks of the past, and they sure make today’s bunch look puny. Philosophers, playwrights, statesmen, artists, poets, orators, sculptors; the ancients had them all. After 2,500 years, they’ve never been equalled. I was once walking around the Greek wing at the New York Met and I ran into Henry Kissinger, whom I knew slightly. He asked me what the population of ancient Athens was. ‘About 20 to 30,000 citizens,’ I answered. He shook his head in amazement. ‘And they produced all this,’ he said.

When I first began learning about the Greeks — my great-uncle was the foremost intellectual of his time and a brilliant pedagogue — I was mystified by the collapse of Athens and Sparta. Athens under Pericles reached its cultural peak: Western man was born. In Sparta, the martial state came into being. No state before or after has even come close to matching the martial readiness and spirit of my grandmother’s birthplace. Just imagine what those two, Athens and Sparta, could have accomplished together. But it was yet another Greek who managed it — to conquer the known world, that is.

The Greeks invented modern warfare, a collision of soldiers on an open plain where courage, skill and physical prowess were paramount. They also invented honor and fair play on the battlefield, and even the protection of non-combatants. Archers and javelin throwers, who launched from afar, were not held in the same esteem as those who fought at great risk to themselves. (I wonder what they’d think of the Saudis dropping ordnance on women and children in Yemen.) Sword and spear were manly and heroic, the rest was looked upon with suspicion.

In the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, the Athenians showed their mettle by fielding citizens, both old and young, from the age of 18 to 60, led by aristocrats. They used a phalanx, eight rows deep. Socrates fought his last battle at Delium aged 46. The Greek hoplite was most likely a farmer, middle class and youngish. He did not fight for booty or plunder but for the defense of his home and the right to vote. I shall never forget the first time an account of the Battle of Marathon was read to me — hearing about the moment when the citizen soldiers of Athens saw the cumbersomely laden Persians getting slowly off their boats and, under Miltiades’s cry to attack, sprinted into the sea and chopped them to pieces. That glorious sprint still thrills me the way it did back then.

Ten years later the Persians returned for another round, this time in Salamis, where Themistocles was waiting for them. Their heavy boats oared by slaves were no match for citizen sailors rowing for military glory and our triremes sunk them by ramming them into oblivion. Weeks earlier King Leonidas and his 300 Spartans had given the Greeks time to plan and execute and Xerxes fled never to return. Alexander the Great finished them off but showed the barbarians — which all non-Greeks were considered to be — what it is to be civilized by sparring Darius and marrying his daughter.

[special_offer]

The Peloponnesian War signaled the end of the two great powers. It was a war of attrition, a foreign concept to citizen-hoplites. One fought for one’s farm and family; only mercenaries fight unending wars. My friend, the wonderful historian Roger McGrath, has written wistfully about citizen-soldiers, comparing the glory days of Athens against the barbarians with those of the United States of America, fighting for freedom and justice, not oil rights: ‘I suspect that historians one day will look back and conclude that America’s great victory in World War Two led to empire-building, power, and glory but also marked the beginning of the end of the United States, and ultimately of Western Civilization. Our reach now exceeds our grasp, and long ago we stopped fighting to defend our land and people.’ Truer words have never been spoken.

McGrath is a nostalgic writer, evoking the time when Greek leaders led from the front or like Henry V, disguised among his troops at Agincourt in order to gauge their resolve. Just imagine Tony Blair leading a column and soiling his trousers, and you’ll get McGrath’s point. But also imagine a world that required those who declared war to fight it. Churchill would have done it, as would Hitler, I’m not sure about Stalin. (He was more of an assassin than a soldier.) Boris I’m certain about. In fact, I can see him charging up a hill waving a sword or a bazooka. Don’t bring up Trump because he has not started anything; in fact, he’s bent over backwards not to shoot. (Except for one Iranian.) Putin would fight from the front, as would Viktor Orbán and any Polish leader, but that is all. (EU leaders would surrender before an enemy even threatened war.)

Any way you look at it, we are now in a situation whereby the worst people on Earth set the agenda — woke activists, celebrities, free speech interdictors, left-wing academics and media people. An allegation is the new guilty, and film, TV and the internet are in pursuit of an ever more fickle and idiotic audience. I think about this while waiting for a chopper to take me back to Athens. Then I’m off to Switzerland, still dreaming of those monumental events I’ve been reading about all week that the youth of today are barely aware of.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.