Wimbledon is here at last, after its absence in 2020. What struck me watching the French Open on television a couple of weeks before was just how much rubbish I had to listen to if I kept the sound on. There are now too many matches broadcast, which means more and more commentators spouting off about the game in the middle of rallies. I don’t know why viewers don’t raise hell with the networks about these non-stop blabbermouths who interrupt our viewing. We’ve become a nation of sheep, accepting everything so-called experts throw at us.

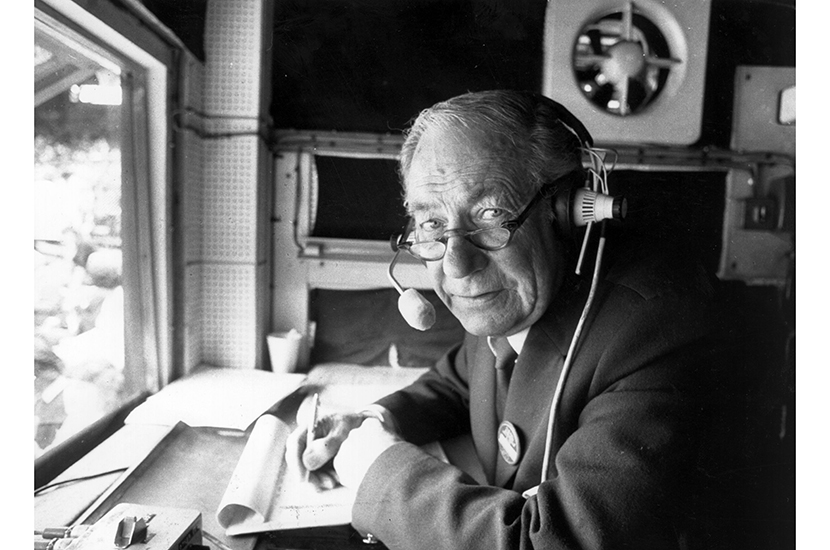

Televised sport needs commentators only before and after the event. Although the Wimbledon lot spout off a lot less than the French Open blabbermouths, I think back fondly to the impeccable Dan Maskell, whose ‘Oh my word’ was as far as he went after witnessing an extraordinary shot. After Maskell came the great South African doubles expert Frew McMillan, who handles the mic as deftly as he handled his racket while winning the Wimbledon doubles title numerous times. Frew was a buddy of mine during our playing days and he’s one of the few today who allow the viewer to enjoy the action without being told non-stop what they are watching.

So why do viewers put up with it? Sport, after all, is a spectacle that needs the minimum of information as the action takes place in full view of the audience. As the great Groucho Marx once told the viewers in Horse Feathers: ‘I’ve got to stay here, but there’s no reason why you folks shouldn’t go out into the lobby until this thing blows over.’ Those highly paid blabbermouths should be forced to give a similar preamble before each broadcast. But I’m just whistling Dixie, as they used to say about lost causes.

The televised sporting event that allows the viewer to make up their mind no longer exists. There is an epidemic of excess on the part of the speakers, sorry, commentators, that is just a way of giving themselves a bit more gravitas. They explain the obvious — that is to say what we have just seen, and then some. Television’s primary mission seems to be to show us something, then to verbalize what we’ve just seen to death. Never mind, perhaps it’s only me who likes to watch tennis without someone explaining to me what I’m watching.

My nerves were tried and fried by watching the French Open, where the rallies can be very long, and the blabbermouths very wordy. The latter are mostly adulatory towards the players, as it’s normal for them to be. But when Serena or Djokovic are on court they really surpass themselves. After losing an important point during a match in Paris, the Serb bounced the ball 23 times before serving. Usually, he bounces it 13 times. If that’s not gamesmanship my name is Coco Chanel. Again, perhaps it’s only me, but American female commentators’ voices, some high-pitched and shrill, particularly get on my nerves. Not Chrissie Evert’s, however. Chrissie was beautifully behaved on court and always looked pretty and feminine while winning. She and McEnroe should be the only Americans employed by European TV networks though Mac is no longer what he was. He was very good when he started broadcasting, and told it like it was. But now he’s joined the rest in being more of a cheerleader than a critic.

One of those American females commenting in Paris remarked how empowering it was to watch a woman taking control of her body. What was that again? If we’re going to have this kind of psychobabble while commenting on a tennis match, I think I’ll start watching wrestling, the pro-kind that involves masked bad guys and screaming women in the audience. If we follow the American way we’ll soon be using the F-word to express sincerity and enthusiasm, not to mention conviction. But let’s get back to the game of tennis.

The reason tennis was once referred to as an elite game (played only by country club types) is easy to explain. Wooden rackets and animal-gut strings made it among the most difficult games to master, if not the most difficult. If one failed to make contact with the ball in the racket’s sweet spot — a diameter of about eight inches — the ball flew out or didn’t go anywhere. If one didn’t step into the ball’s path and take it on the rise, the return just died. If one didn’t meet the ball sideways, ditto.

All of the above are now no-nos. Strings grip and slingshot the ball; graphite, titanium and all sorts of rocket material-made rackets have turned everyone into a champ. Open-stance forehands, swing volleys, and from-the-baseline drop-shot attempts are now obligatory.

I remember an article about the fastest server in the game, Pancho Gonzales, serving close to 113 mph. Today a 15-year-old’s second serve tops that speed. See what I mean about tennis being a different sport than the one I grew up competing in? Touch and guile were equal to power, so don’t compare the greats of today with those of yesteryear. Rod Laver, Lew Hoad and Roy Emerson were as good if not better than today’s great troika, and they didn’t have the entourages: no dermatologists, cosmetologists, electrolysists, masseurs, coaches, trainers, dieticians, strategists and cheerleaders.

Enjoy Wimbledon with or without sound, and take it from Taki: tennis is a totally different game.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.