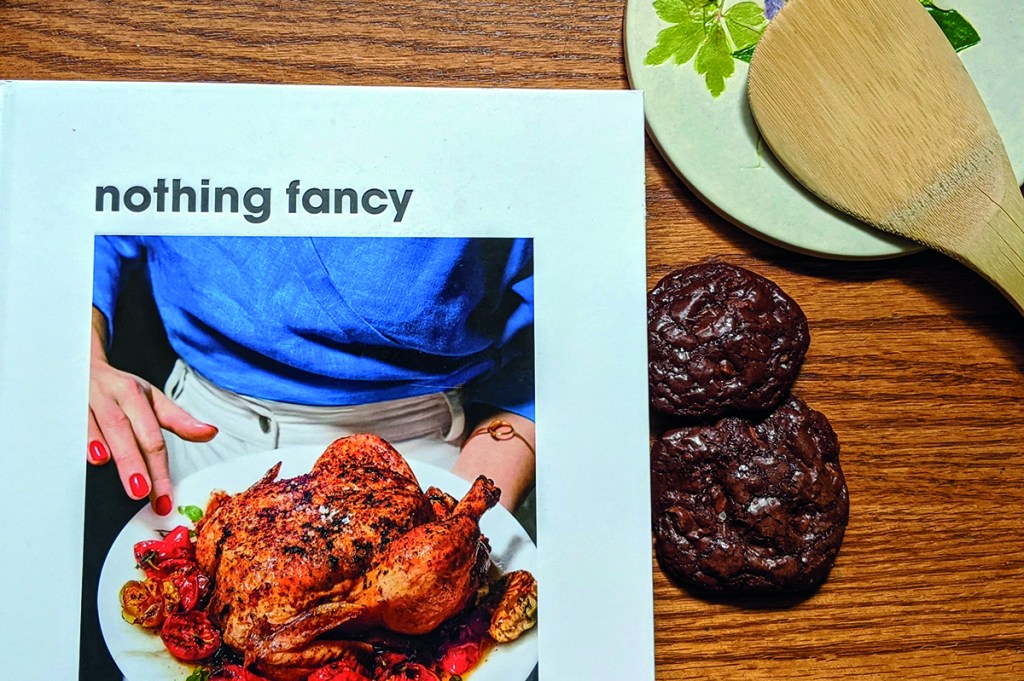

I fled New York City in March for my hometown in Pennsylvania. I brought with me one suitcase, a good chunk of it filled by my favorite book: the bestselling Nothing Fancy by Alison Roman of the New York Times.

I’m now facing weeks here with three shirts and an impractical selection of underwear, but I regret nothing about my packing. As my father drove up the turnpike to evacuate me, I had decided in a burst of wartime can-do spirit that my contribution to the household would consist in cooking for the family, and damn if I wasn’t going to make a go of it.

There was more than a little self-interest in this idea. Like all middle children, I long for a chance to shine in front of my family. Unlike any of my seven siblings, I’ve never been a member of a sports team, brought home a partner anyone liked, or worked for a legitimate employer, like a hospital or the Marine Corps. But I am a very good cook.

I should mention the central challenge involved with cooking for my family, the reason I’ve never tried before and why my current quest is so ambitious. His name is Dad.

As a child I believed my father’s culinary tastes were simply grown-up tastes, and that to be a grown-up was not only to like gross things, but to be extremely particular about the gross things you liked. He brought home inedible candy: Mary Janes, Necco Wafers, off-brand Airheads in flavors like ‘banana caramel’. He’d return from the store with tinned Vienna sausages, canned beets, Spam. When he learned to pickle, he pickled hardboiled eggs. He will not eat fruit. His favorite dessert is something called junket, which Wikipedia describes as ‘milk heated to body temperature’.

Cooking dinner for my father subjects me to rules that combine arbitrariness and inflexibility in a way usually reserved for game shows. He requires meat with every meal. No fish, no lamb, no veal. Pasta rarely, chicken only once a week, and then no dark meat. He would eat venison if I bagged the deer myself. When I enterprisingly produced a pound of chorizo for enchiladas my father told me ‘I prefer linguiça.’

‘Oh, I’ll make do with just about anything,’ my father will say, before refusing to touch a platter of braised chicken thighs. In short, my father’s taste in food is a performance art-level troll on the scale of the man’s entire life. My mother reacted sensibly: with a 35-year-long defensive crouch in the trenches of the kitchen. She responded to his bizarre inclinations by ignoring them entirely and feeding us with inoffensive combinations of ground beef, onions, rice and kidney beans. If Dad doesn’t like something, well, that’s what the hot sauce is for.

Alison Roman’s tastes are like my father’s: particular, strident and requiring a capacious definition of the word ‘unfussy’. She has memed my entire generation into liking anchovies — impressive, considering that my father has never persuaded me to try a pickled peach. Assured by her confidence, I turned to Nothing Fancy on my first day home.

My debut Roman meal for my quarantined household (me, my parents and my 16- and 22-year-old brothers) was Harissa-Rubbed Pork Shoulder with White Beans and Chard. I had used precious suitcase space for a jar of harissa: the local grocery stores stock marinara in the international aisle. My father gamely went to three different panic-stricken supermarkets to find the other ingredients for this meal I’d promised him. Expectations were high.

He watched curiously as I rubbed down six pounds of pork shoulder with a pungent harissa-and-vinegar marinade, waited patiently as the shoulder roasted for four hours, eyed skeptically while I chopped cilantro and bok choy. On pins and needles, I watched him take the first bite in his seat at the head of our dining room table. ‘These beans,’ he said slowly, ‘are kickin’.’

Success! My God, it was good. I basked in the respect and admiration glowing from my family’s eyes as I served them all seconds from the enormous hunk of meat. They couldn’t have been happier if I’d turned up with a real live man.

I’ve followed up almost every night. Sometimes I make decadent Roman recipes like spicy meatballs in tomatoes, or sticky chili chicken with pineapple, with blackberry cornmeal cake for dessert. Sometimes I stick to more workaday, pantry-staple one-pot-type dinners, often accompanied by, yes, fresh-baked bread.

My copy of Middlemarch lies untouched on the floor of my childhood bedroom. Nothing Fancy gets smudged, splattered and dog-eared as I cook and cook and cook. Like many people, I’ve discovered that the most comforting thing about comfort food can be making it: having something to give the loved ones who take care of us, in all their idiosyncrasies. That I have acceptable meals to offer my picky father pales in comparison with what he has to offer me: a safe haven, a family, a home and, some days, just something to do.

If you hear of anyone on earth who has any extra sourdough starter, would you let me know?