All across the north the ritual bulls have already been slaughtered. I am waiting for the invitation from our Samburu neighbors to set off on a walk into the forested hills with my boy Rider to visit the great thorn enclosures where thousands of youths are to be circumcised. Drought in the low country may delay the ceremonies, but with any luck some clans will go ahead as planned with this great rite of passage that happens every 15 years or so. It is an immensely exciting cycle of events to observe an entire generation become initiated into the warrior age set, a process that is esoteric to us, yet makes complete sense in the passage of a man’s life in this modern world. Around the time that boys become warriors — who roam with cattle, defend the clan’s honor, gorge on meat and adorn themselves like peacocks — the next age set enters elderhood, at around 30 or so, when men at last are permitted to marry and acquire cattle wealth.

When I was around Rider’s age, I made friends with a Samburu youth up north. His name was Damayon and we were best friends. We climbed trees, threw rocks and hurled spears, swam in river pools and trekked long distances. In our tests of strength, our aim was never to give in to pain or fear. My friend’s talk rarely strayed far from his love of cattle, the wild creatures, his rugged mountains, the pastures and the singing wells. I was an English teenager in glasses, with feet in shoes. I so envied Damayon the cicatrix patterns on his cheeks and upper body, his beaded adornments, his agility and ascetic toughness, his weapons, the way he saw his universe and the life ahead of him. He wanted nothing from my world, and he was unfazed by it all, though gently respectful when he came to stay with my family and sat at the table cracking jokes to amuse my mother, or answered my father’s endless, earnest questions. I had no illusion I was anything other than a boy from a separate world, but for me knowledge of Samburu things gave me joy, as did my growing collection of knives in rawhide scabbards, spears and beaded bracelets. Folded in my rucksack wherever I went, I had a good map of Kenya on which I marked each safari, camping spot, points of interest and valued experience, until it was completely scribbled over.

With Damayon I first saw a Samburu dance, when youths swayed in snaking lines, each warrior joining the rhythmic chorus, his jaw crushing down into his throat to emit the grunt of a lion, stretching his chin skywards to roar like a bull, every dancer in turn separating from the line suddenly to leap high into the air on rigid legs, landing on the dry earth with a stamp in a cloud of dust before the line absorbed him and another dancer came forward. I was a spectator watching this chorus of growls and roars, this leaping which reached a pitch of energy when dancers began to shiver in a state of trance. Sometimes a youth fell out of the line, convulsing like an epileptic, his eyes white in their sockets, foaming at the lips, cradled by his fellows.

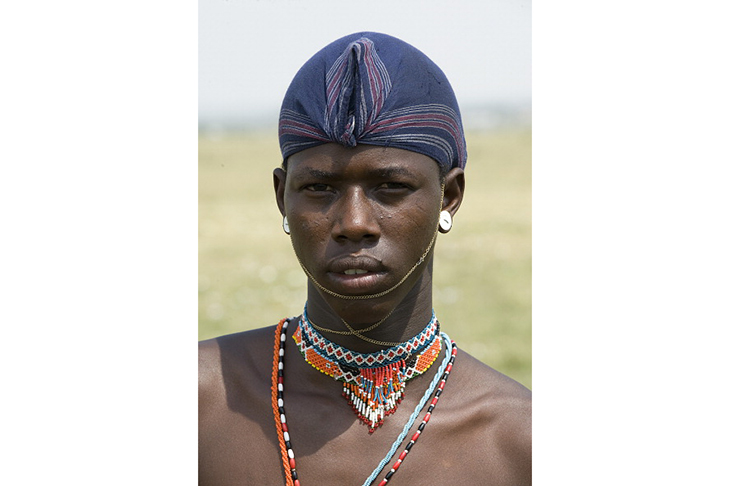

The day arrived when Damayon and I said goodbye to each other. His scalp was shaved, leaving a top knot from which hung strings of blue beads tasseled with copper-colored insect wings. He was dressed in a goatskin cloak stained black with charcoal, ready to vanish into the secluded places in the mountains with his age-set mates, where nearer to god — Nkai — they would chant their plangent songs. The last time I ever saw Damayon, he was marching off with the other initiates singing the circumcision song, which to me sounded like a dirge for lost childhood.

I thought about all the ordeals the two of us had set ourselves. For me they were just games, but for my young Samburu friend they were preparations for the day he would bleed under the circumciser’s knife and he must not flinch, must show a calm face against pain to avoid the everlasting shame of being a coward. After being cut they trekked off into the wilderness until their injuries healed, wearing mantillas of black ostrich plumes and the bird pelts of robin-chats and francolins, their ebony faces daubed with white ochre.

I never saw my friend again. I hope he is still up there in the north, living a good life as an elder now. I went off to face challenges of a different type but I never forgot my time as a boy in Samburu’s beautiful country among such magnificent people. It was one reason why we came back up here to ranch cattle in Laikipia, living close to Damayon’s people. Rider has grown up here and it is wonderful that soon he might witness the great dances I saw as a boy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.