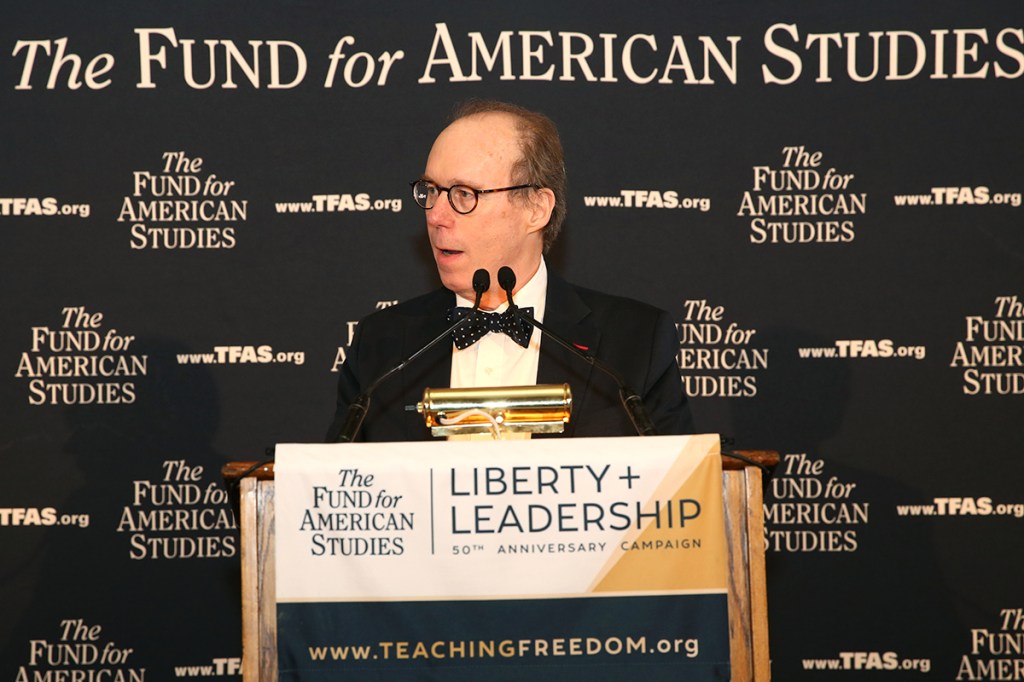

Roger Kimball,

Spectator contributing editor, publisher of Encounter Books and editor of The New Criterion, was presented with the Thomas L. Phillips award at the TFAS Journalism Awards Dinner in Manhattan last week. Below is his acceptance speech.

I am grateful to the Fund for American Studies for the singular honor of bestowing upon me the venerable Thomas L. Phillips Award. You will find a list of previous honorees in your program. To say that it is an impressive list would be to dally with frivolous litotes. It makes me blush to be among such company.

Had the fates been more generous, one name that I feel sure would occupy a place on that escutcheon is that of Joseph Rago. Joe, who died at the shocking age of 34, was known to the world at large as a brilliant editorial writer for The Wall Street Journal. His labors there won him a Pulitzer Prize when he was still in his twenties.

For more than a decade, he was known to the readers of my magazine The New Criterion as a contributor and, towards the end of his life, as our fiction critic, a post from which he ably lived up to the poet Horace’s injunction to delight as well as instruct. I am happy to note that Joe’s parents, Nancy and Paul Rago, are with us tonight. I wish that he could be as well.

It what was perhaps his last piece for The New Criterion, Joe cast an amused though gimlet eye over the eructations of impotent puerile fury that greeted the election of Donald Trump among the literati. ‘This ages-nine-and-up coping mechanism,’ Joe wrote, ‘does capture something significant about political and literary culture, circa 2017. Too much of politics, and of human experience,’ Joe went on, ‘is being fitted into neat good-bad binaries that appeal to feelings and status, not to the accurate representation of the world.’

‘The accurate representation of the world.’ How quaint that phrase sounds in an era of fake news and the wanton trampling of truth, not least by those entrusted with its dissemination: journalists, yes, but also many educators and other unworthy custodians of the achievements of our culture.

The institution that became the Fund for American Studies was founded in 1967, a period of hysterical narcissism and malignant dissimulation not unlike our own. Indeed, a comparison between the two periods, though beyond what we can discuss tonight, would be illuminating, both in the similarities and the differences of the pathologies at play. Among the founders of the Fund was my friend the late William F. Buckley, Jr., a man who with graceful wit, at once decorous and deadly, also dedicated his life to ‘the accurate representation of the world.’

It is interesting to ask what Bill, who died in 2008, would make of the contemporary cultural and political scene. He’d witnessed similar follies throughout the 1960s and 1970s. And after all the Sage of Ecclesiastes was right: there is nothing new under the sun, though many of our most prominent cultural figures seem to believe that they occupy a unique perch at the very apogee of virtue and moral rectitude and are therefore entitled, O how entitled, to discard the achievements and admonitions of the past as so many false starts and dead ends on the way to true enlightenment, which is to say to whatever they happen to believe at the moment.

It is important to remember how general was the assault on our civilization in the Sixties. It wasn’t just protests against the Vietnam War, the sexual revolution, the new hedonism. What was aimed at was nothing less than what Nietzsche called the transvaluation of all values. Among other things, it represented a categorical repudiation of the American consensus, not just its engines of prosperity and individual liberty but also the basic tenets of our self-understanding, tenets that went back through English liberalism and the Scottish Enlightenment to the political meditations of the Greeks and the Romans.

We see something similar today in a different modality. In some ways, indeed, the assault on the fundamental values of our civilization is more thoroughgoing today than it was in the 1960s. This is partly because those conducting the assault are not launching their fusillades from outside the establishment but are themselves well integrated into and often highly-placed members of the establishment. They are, in a word, the Elite. It is also partly because the assault is no longer undertaken in the name of freedom and truth, however spurious, but, strange though it sounds, against both.

George Orwell was right when he observed that the first indispensable step towards freedom is the willingness to call things by their real names. We — which is to say, our masters in the media and cultural establishment — have lost that fortitude. The triumph of political correctness has encouraged an epidemic allergy to candor. The hope is that the embrace of euphemism will alter not only our language but also the reality that our language names.

And to a large extent, it is working. Unfreedom does not become freedom by calling it free. Reality continues to check the fantasies of our narratives. But the misprision can help spread and reinforce the fog of self-deceit.

There is a sense in which the triumph of political correctness erodes free speech chiefly by negative means. It promulgates speech codes, rules against ‘hate speech,’ and the like, but I suspect that its gravest damage is done by instilling a timidity of spirit among its charges.

A reluctance to speak the truth instills an unwillingness or even inability to see the truth. Thus it is that the reign of political correctness quietly aids and abets habits of complacency and unfreedom.

This atmosphere of supine anesthesia is an invitation to tyranny. It took several centuries and much blood and toil to wrest freedom from the recalcitrant forces of arbitrary power. It is a melancholy fact that what took ages to achieve can be undone in the twinkling of an eye.

I do not think it is properly appreciated just how bizarre it is that socialism appears to be making a serious comeback, not just as a common-room amusement among ignorant students who have no idea what socialism is, but also among presidential candidates and members of Congress, some of whom, anyway, know only too well what that murderous ideology entails.

Winston Churchill was too kind when he said that socialism was ‘the philosophy of failure, the creed of ignorance, and the gospel of envy.’ All that is correct. But beyond that, socialism rests upon two fundamental goals, the abolition of private property and the equalization of wealth. A corollary to the achievement of those goals, as socialist totalitarians the world over have instantly realized, is terror and a police state. And yet here we are with serious proposals to institute socialism in the United States.

It seems to me that we are at a crossroads where our complacency colludes dangerously with the blunt opportunism of events. Courage, Aristotle once observed, is the most important virtue because without courage we are unable to practice the other virtues. The life of freedom requires the courage to recognize and to name the realities that impinge upon us. Day is Night. Peace is War. Love is Hate. Out of such linguistic capitulations, as Orwell showed in Nineteen Eighty-Four, totalitarian tyranny is born. We’ve all read the book. But have we learned that hard lesson?

Free speech, it turns out, is like other freedoms: its victory is never permanent. It is a melancholy truth that the right of free speech, like other civilizational achievements, must constantly be renewed to survive. That was one of Edmund Burke’s central insights. It is also, incidentally, one of the founding insights of the Fund for American Studies. But it is an insight that is regularly forgotten — until reality intrudes upon our reverie to remind us. Every generation finds that it must work anew to win or at least to maintain the freedoms bequeathed to it by earlier generations. What was argued for and won yesterday is today once again up for grabs. Which moves patience and perseverance to the head of the queue of political virtues. You already made the argument. But it always turns out that you must make it again.

During the Japanese bombardment of Shanghai in 1932, the Austrian essayist Karl Kraus was anguishing over the placement of commas in a column. It might seem futile at such a moment, he told a friend, but concluded. that ‘if those who are obliged to look after commas had always made sure they were in the right place, then Shanghai would not be burning.’

Was that hyperbolic? Perhaps. But the general point holds: language matters. Achieving ‘the accurate representation of the world’ is not only a linguistic desideratum, it is also a political imperative. Much of our culture has colluded against the accurate representation of the world. We owe the Fund for American Studies a great debt for understanding what is at stake in the seemingly pedestrian activity of telling the truth. Long may it prosper.