Do you worship Dennis Hopper? Do you get your kicks from sagas dedicated to the lives of the rich and famous? And do you eat up rehashed accounts of the far-out West Coast zeitgeist in the 1960s? If so, Mark Rozzo’s Everybody Thought We Were Crazy is the book you’ve been waiting for.

Rozzo starts in medias res: it’s November 1961, and Bel Air is burning. As the firestorm approaches, Hopper and his unlikely wife, blue-blooded poor-little-rich-girl Brooke Hayward, grab her kids and abandon their house — but not before Hopper grabs a Milton Avery painting and throws it in the back of the car. This high drama is followed by a teaser of things to come, sketching the scene that arose around the couple’s next home, the legendary 1712 North Crescent Heights, which Rozzo says “became the era’s unofficial living room.”

Early chapters furnish the couple’s origin stories. Hayward is the precocious but unhappy daughter of Hollywood royalty. Her father was a top agent, her mother was the “utterly insane” film star Margaret Sullavan, and her best friend was Jane Fonda. After her parents’ divorce, she was accepted at the Actors Studio in 1958, appeared on the cover of Vogue in 1959, married, had children, got divorced and embarked on an acting career, where she met Hopper. He had appeared in Rebel Without a Cause, had become a disciple of James Dean and keeper of the sacred flame and been blackballed by Hollywood for his impossible Method antics before falling in love with Hayward.

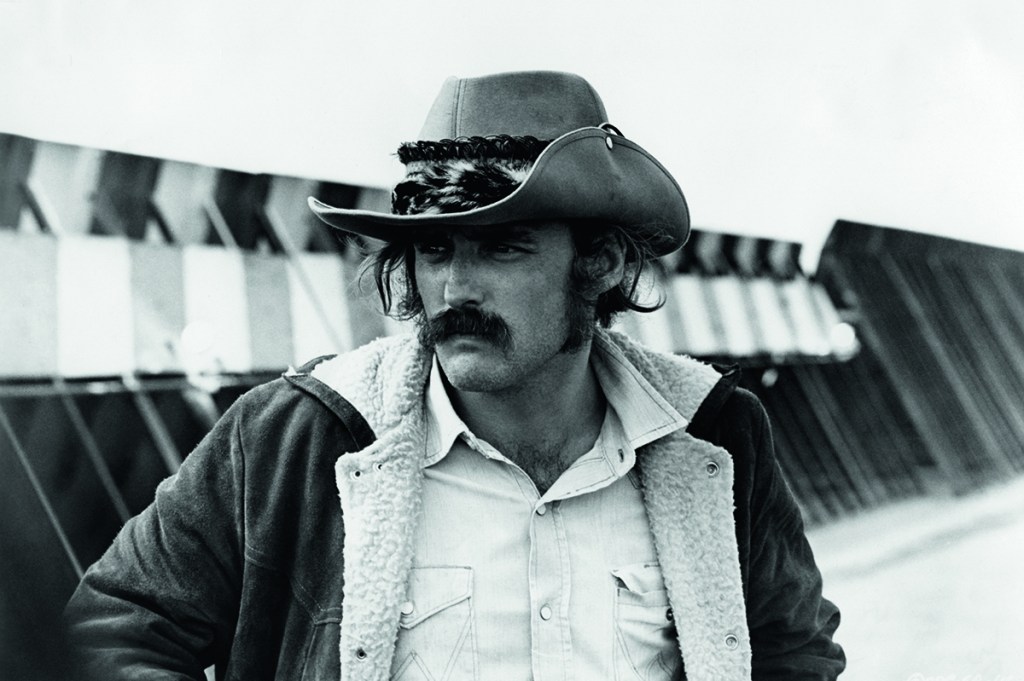

The book focuses on the life Hopper and Hayward made together, as they became embedded in LA’s burgeoning art scene and as Hopper began extensively documenting the SoCal cultural ferment and its denizens with his Nikon. (Arguably it’s his photography that’s his true legacy rather than the seven films he directed or his hundred-plus mainly terrible movie performances.) Bridging the divide between bohemia and old-school Hollywood, they were a power couple of sorts and became art collectors. While Hayward is laid up after giving birth to their daughter, Hopper announces he’s bought a work “by a New York painter named Andy Warhol.” Rizzo is happy to print the legend: “For all intents and purposes it was the first Warhol soup can painting ever sold.” Bought with Hayward’s money, naturally.

Hayward set about filling their new home with artfully curated antiques and bric-a-brac, turning it into a “design laboratory.” Her collection of objets existed in “kaleidoscopic equilibrium with the futuristic art pieces. It was old and new, high and low, and utterly at odds with the prevailing mid-century-modern appeal to minimalism and order.” But then came the drugs. By 1965 the explosion of Los Angeles’s rock and counterculture scene provided Hopper with a new world to document and in which to immerse himself. With his frustrated ambitions to make a film that would blow everybody’s minds and bury old Hollywood, Hopper’s megalomania grew exponentially, fueled by nonstop drinking and drug use. Hayward stood by while Black Panthers and Hell’s Angels crashed in their living room and Hopper descended into near-psychosis, at one point threatening their kids with a loaded gun. When he broke her nose, the end was in sight — almost.

In 1968 Hopper and Peter Fonda made Easy Rider — an influential rather than distinguished film — and after Hayward told her husband she “didn’t believe he and Peter were on a path to cinematic glory,” they agreed to divorce. Hopper comes off as a Zelig figure if we’re to believe this book. He was there when Lenny Bruce was arrested in the middle of his act. He was there on the frontlines at the march from Selma to Montgomery. He was there for the opening of Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable. He photographed the Watts and Sunset Strip riots, the Monterey Pop Festival and the Gathering of the Tribes in San Francisco. He was there in 1965, stoned out of his head, at Jane Fonda’s legendary July Fourth Malibu beach party.

Having died in 2010, Hopper isn’t available to pile on the self-aggrandizement — but no problem, Rozzo has it covered. He recounts, for instance, the story of how Hopper persuaded Marcel Duchamp to sign a stolen hotel sign, “thereby creating — or co-creating — one of his final works.” And Rozzo reports Hopper’s claims that when he met Charles Manson in prison, Manson told him his fake insanity stratagem was inspired by Hopper’s role in a 1963 episode of The Defenders.

It’s unclear if Rozzo ever met Hopper; the author falls back on reams of extant interview material and books. Rozzo had ample access to Hayward, however, and she inevitably gets the last word. If this story of a couple is one-sided, it’s Hopper who provides all the color. Fatally, Rozzo shows almost no critical distance from his subjects. He refers to them by their first names throughout, as if he thinks of them as personal friends.

Everybody Thought We Were Crazy reads like a book-length Vanity Fair piece — no great surprise given that Rozzo’s one of the magazine’s contributing editors. What passes for writing here is mainly the stringing together of an endless succession of quotations from other people’s work and anecdotes from those that were actually there. Rozzo should have gone all the way and written an oral history à la Jean Stein and George Plimpton’s Edie. As it is, this admittedly thoroughly researched book is as insubstantial as it is exhaustive.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.