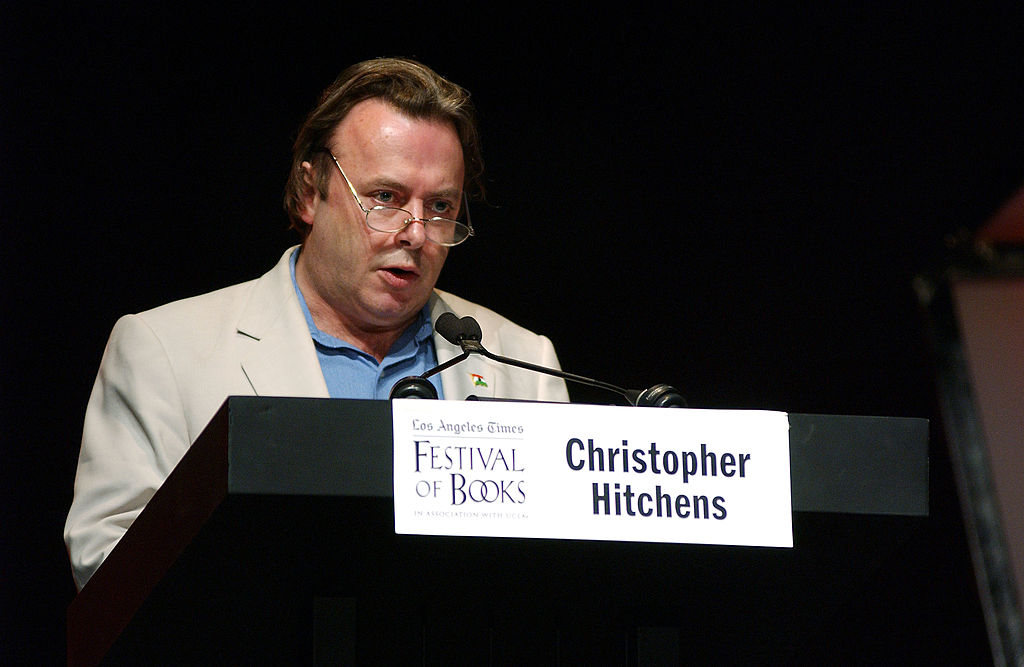

Today marks ten years since the death of the writer Christopher Hitchens, one of the most distinctive voices in twentieth and early twenty-first century journalism. He probably would have been amused by the way virtually every sector of political and social thought has subsequently claimed him as their own in his posthumous form. Whether you’re a right-wing demagogue, a left-wing woke activist or a hand-writing neocon, you can surely find the perfect Hitchens quote to suit your purposes.

Hitchens died far too young at 62, but then he had already lived the kind of full-throated bacchanal existence that his peers could only look upon in envy. He wrote over thirty books, which alternated between the profound and the provocative, and millions of words of journalism. His drinking and smoking were the stuff of legend, and no doubt contributed to his premature death from esophageal cancer. Writers who were sent to profile him were often to be found, aghast, in the gutter after an all-night session on the wine and whisky, while a cheery Hitch would head off to write his copy, apparently unscathed by his alcoholic adventures.

It is easier to define what Hitchens didn’t stand for than what he did. He was opposed to cant and hypocrisy in all its forms, and his 2005 debate with George Galloway represented a particularly heartfelt battle royale for him. His opponent may have memorably ridiculed him as “a drink-sodden former Trotskyist popinjay,” but Hitchens was able to win the last laugh when he remarked that he was “depressed by the ease with which a cheap point can get applause in the mouth of a really unscrupulous person. When I turned my head — which I tried not to do — it was like looking straight into the piggy eyes of fascism.”

He reveled in apparent contradictions. He was a staunch man of the left who became an equally staunch supporter of the Iraq war. He was Gore Vidal’s anointed “dauphin” who savagely attacked his mentor as “Vidal Loco” in 2010, calling him a “crackpot” who had embraced 9/11 conspiracy theories. He was the expatriate Englishman par excellence, entirely at home in the finest salons and restaurants of Washington, who nevertheless retained the exile’s near-desperate love of his former land, particularly its literature. When asked who his favorite writers were, he unhesitatingly listed Kingsley Amis, Evelyn Waugh and PG Wodehouse, none of whom shared his politics or worldview, as well as the more predictable figure of George Orwell.

Orwell wrote of Dickens that he was “generously angry,” and it is that generosity in rage that defines much of Hitchens’ prose. He was perpetually surprised by the hypocrisy and venality of the contemporary world, and tore into it with spirit, vigor and rare wit. But he was not a sneering and superior fellow, unlike so many of his fellow columnists. Instead, he extolled the virtues of plain (if self-consciously ornate) speaking, original ideas and having something interesting to say. Not for him the endless, empty pieces and books that seemed to have been put together in an afternoon. His writing always felt as if it had the virtue of lived experience, even if that experience had been obtained through the bottom of a bottle of 20-year-old whisky.

There has been much debate over what Christopher Hitchens would have been today. Would he have been an ardent social media zealot, forever starting flame wars on Twitter, or would he have stylishly eschewed it? Would he have loathed wokery and cancel culture, or defended their right to exist? What would he have made of Covid, of Trump’s presidency, of Biden ‘n’ Kamala, of the Kardashians? We shall never know, and it is fruitless to attempt to construct elaborate counterfactuals. But what we can be certain of is that anyone who stands against puffed-up pomposity and grating grandiosity undeniably owes a debt to Hitchens, who, in spirit, remains on their side.

As the man himself said, “Whenever I hear some bigmouth in Washington or the Christian heartland banging on about the evils of sodomy or whatever, I mentally enter his name in my notebook and contentedly set my watch. Sooner rather than later, he will be discovered down on his weary and well-worn old knees in some dreary motel or latrine, with an expired Visa card, having tried to pay well over the odds to be peed upon by some Apache transvestite.”

Seldom was a truer, and funnier, statement written. Its author continues to be an inspiration to those who applaud wit and freedom in all their literary forms.