I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the last pages of Naked Lunch at dawn looking for an angry fix of good literature, angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection between plot and prose, who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up reading Kaddish, who bared their brains to the delights of On the Road in the pursuit of just a fraction of the “angels staggering on tenement roofs illuminated.”

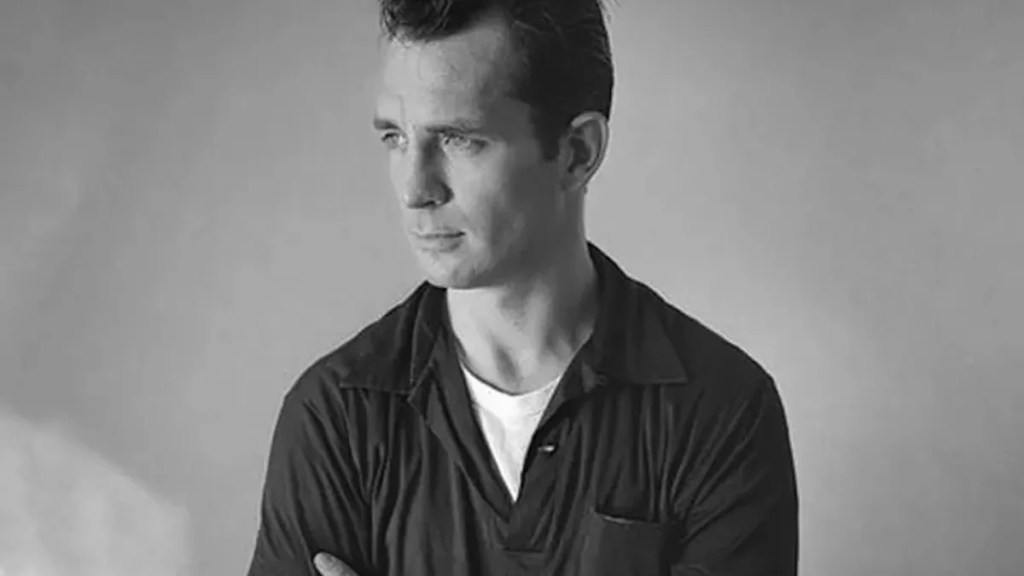

Everyone knows the Beats: from Jack Kerouac to William Burroughs to Allen Ginsberg, their influence has been undeniable, if not always delightful. And on March 12, their lodestar, Jack Kerouac would have been 100 years old.

Kerouac became famous after the initial success of On the Road (1957), but his position as the apostle of beatnikery was not an easy one. He died aged forty-seven in 1969, after a lifetime of heavy drinking and a later-life of rebelling against his early countercultural fame. In the years before his death, he reaffirmed his near-Republican Catholicism, and had no time for the radical politics that had so consumed the movement.

If Kerouac was able to distance himself from the Beats, the rest of us have not been quite so lucky. On the Road regularly makes the lists of best American novels, while quotations from its scurrilous pages litter Tinder profiles and Instagram bios. The type of man who talks nothing but The Dharma Bums at a house party has become something of a meme in his invidious ubiquity. “It just really spoke to me, yah. I would give you my copy but my lousy ex-girlfriend has it.”

But if the premise of The Dharma Bums is a search for a Buddhist, spiritual meaning to life, On the Road lacks such a motive. Sex, drugs, more sex — but endless bop and jazz instead of rock ‘n’ roll.

It is well known that Kerouac’s fictional stand-in, Sal Paradise, does not treat the women he meets on his highway journeys especially well. He leaves Terry behind after a slim few pages, and very little mention is made of her reaction to this abandonment. Dean Moriarty, the fictional stand-in for Neal Cassady, leaves one wife behind with a newborn child, hits an interim girlfriend for sleeping with other women — and complains about injuring his hand in the process — and then marries another woman he’s knocked up, only to leave her for a former flame a few pages later.

If I wanted to hear about the callous treatment of women at the hands of mediocre, faux-intellectual, self-indulgent whingeing men, I’d just spend more time around boys my own age, rather than hours wading through impenetrable prose.

This casual attitude to sex, relationships, and abuse was not limited to fiction. Kerouac’s girlfriend of two years, Joyce Johnson — now a successful author in her own right — admits that he treated her awfully. This, of course, did not stop her from describing him as the love of her life, nor from writing his biography in 2012.

And this is the eternal problem of the Beats: we know they were awful people (as a case in point, there were no fewer than two homicides in the wider group) and even the most besotted readers would admit that their writings are quite hard to get through. Yet they are still deified unironically as the “angels” and “saints” they proclaim themselves to be.

There is, of course, an argument to be made that their descriptions of a freewheeling, sexually liberated, drug-taking group of young people was what America needed to shake her out of her 1950s stupor. Ginsberg’s Howl was embroiled in a 1957 obscenity trial — three years before Britain was rocked by a similar legal battle over D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover — and was eventually cleared of all charges, as it was lauded as a work of “redeeming social importance.”

But the heights of sexual freedom are not matched by the prose used to describe them. In Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, bisexuality, personified strap-ons, and the filthiest of group sex are all presented with the erotic allure of a shopping list. “His face disintegrates as if melted from within… Johnny scream like a mandrake, black out as his sperm spurt, slump against Mark’s body an angel on the nod.” Benzedrine does not a pretty sentence make.

There was, evidently, some good to come out of the Beats. I would be lying if I said a part of me didn’t adore Ginsberg’s paean to Walt Whitman, “A Supermarket in California,” and the folk-rock legend himself, Bob Dylan, was influenced by the group. But while Dylan’s autobiographical Chronicles Vol.1 (2004) made for brilliant reading, his impenetrable poetry volume Tarantula (1971) is yet another stream of consciousness that never should have been put down on paper.

One hundred years on from Kerouac’s birth, it is clear that his influence is not going to end any time soon — the much-hyped Fuccboi, published this year, has more than a hint of the Beats about it. But while we must be grateful for a literary culture that has no problems with shifting sexualities, experimental prose, and soul-baring frankness, surely it’s time to hit the road, Jack.