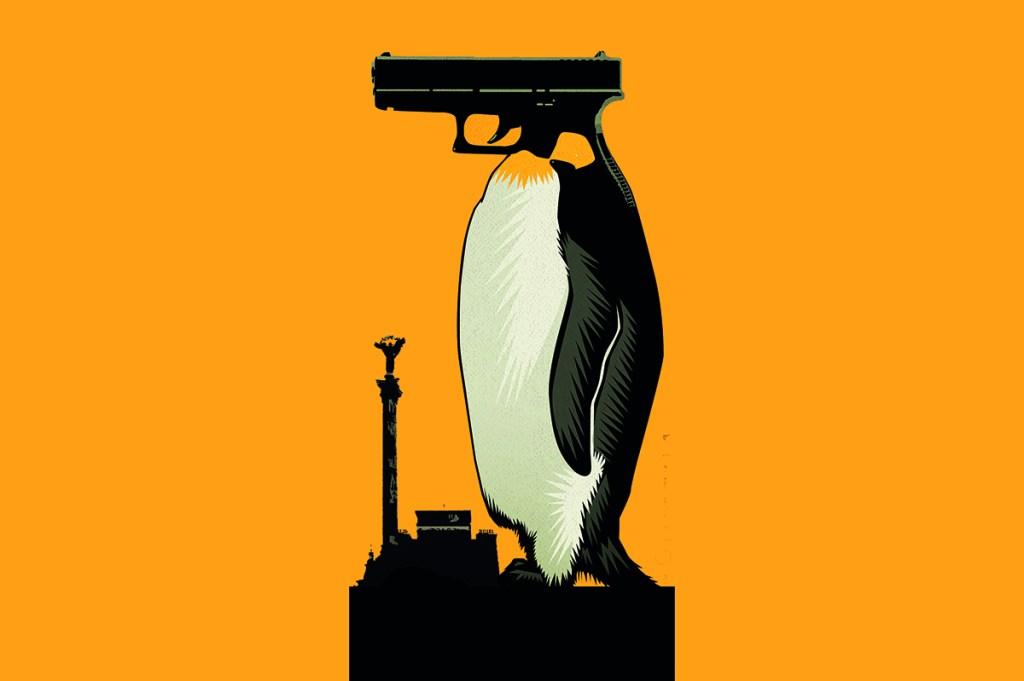

“They don’t treat people nowadays, let alone penguins.” When Americans ask what went wrong after the fall of the Berlin Wall, this wry comment on the state of Ukrainian healthcare in the 1990s isn’t a bad place to start. It’s also typical of the darkly funny Death and the Penguin, an account of a young writer in Kiev and his pet penguin, Misha, formerly of the city zoo.

Did I say Kiev? Of course I meant Kyiv. It has lately become unfashionable to mention the commonalities between Ukraine and Russia, lest you give aid and succor to Vladimir Putin. But Putin’s propaganda resonates because it contains a grain of truth. Despite war and ethnic conflict, Russia and Ukraine have a great deal of shared history.

Death and the Penguin, published in 1996 and one of the first modern Ukrainian novels to gain attention in the West, was written in Russian. Throughout the book, Kyiv and Kharkiv are rendered as Kiev and Kharkov, Russian names that were once commonplace on American maps and atlases. Andrey Kurkov, the book’s author, was born in St Petersburg and describes himself as an ethnic Russian.

Other commonalities appear throughout the novel. A policeman casually mentions the possibility of transferring to Moscow the same way an American might discuss moving from Denver to New York. In December, children wait expectantly for “Grandfather Frost,” a secular Santa figure from the Communist era who lives on in post-Soviet Ukraine and Russia. On New Year’s Eve, the policeman notes “they’re already clinking glasses in Moscow” before sitting down to watch The Diamond Arm, a 1960s Russian crime caper.

Some of these commonalities are a result of Soviet rule; others stem from deeper linguistic, historical and cultural ties. Recently, Kurkov has suggested that Ukrainian writers will no longer write in Russian. War is changing Ukrainian identity into something more distinct and less permeable.

Death and the Penguin follows Viktor, an obituarist who wants to write short stories, and his unwitting entanglement with the Ukrainian mob. Viktor’s underworld encounters are sometimes funny and often terrifying. Thanks to Hollywood blockbusters, Americans are dimly aware of the dominance of organized crime and the black-market economy in many corners of the post-Soviet world. The details are quietly astonishing.

Lithuania, a member in good standing of the European Union and NATO, is a post-Soviet success story. Lithuanian President Rolandas Paksas was forced out of office in 2003 for ties to the Russian mob. Further east, the “informal economy,” often dominated by criminal elements, matches or even exceeds legitimate activity. In 1998, the Russian government estimated that 40 percent of private businesses and 60 percent of state-owned companies were controlled by the mob. In 2021, according to one estimate, the black-market economy made up 44 percent of Ukraine’s GDP.

The Ukrainian mafia lurks menacingly in the background of Death and the Penguin. Viktor’s editor, the mysterious “Chief,” has sent his wife and son to Italy because “it’s quieter there.” Viktor’s obituaries for powerful figures who die under mysterious circumstances make oblique reference to financial chicanery and suspiciously large money transfers to Western banks. Viktor realizes the extent of his involvement with the Ukrainian underworld just as the Chief has to leave town suddenly. Naturally, the boss needs to borrow some American currency before the flight.

Crime and disorder are symptomatic of broader social and economic breakdown. How does an underemployed writer come to own a pet penguin? The city zoo could no longer afford to keep it. Once the zoo got rid of the penguins, it also got rid of its penguinologist, whom Viktor finds alone and sick in his apartment. After he is hospitalized, the penguinologist tells Viktor he has been offered “American injections” if he signs over his apartment to the attending physician.

Then there is the drinking, another sad commonality between Ukraine and Russia. Death and the Penguin doesn’t dwell on its characters’ prodigious consumption of vodka, wine, beer, cherry brandy and cognac; it’s simply part of everyday life, like ice and snow in the winter. The extent of alcohol abuse in post-Soviet Russia and Ukraine, and the accompanying decline in life expectancy, are telling indicators of societies on the verge of collapse.

The characters in Death and the Penguin often make wry references to this miserable state of affairs. On New Year’s Eve, Viktor and a friend toast “to not being worse off.” Westerners sometimes speak of an enduring streak of Russian fatalism. A similar Ukrainian tendency is evident throughout the book.

The political situation has changed dramatically since Death and the Penguin was first published. After the hopeful 1990s, relations between Russia and the West have reached a post-Cold War nadir. Ukrainian and Russian teenagers are now killing each other over the Donbas. A Cold War victory that promised peace, prosperity and the gradual assimilation of the former USSR into the West’s orbit has turned sour.

Where did it all go wrong? Death and the Penguin suggests an obvious if uncomfortable answer. While many Central and Eastern European countries have thrived since the fall of communism, Russia and Ukraine suffered disorder, misgovernment and social breakdown. Until recently, the West could afford to ignore this uncomfortable reality. But as the United States ships billions of dollars in arms to Ukraine and Europe braces for a winter without Russian gas, the failures of the 1990s have come back to haunt us.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2022 World edition.