In September 1890 a Frenchman called Louis Le Prince left his brother in Dijon and boarded a train to Paris, with the intention of connecting to London and then to Leeds, before finally joining his wife Lizzie and family in New York. But the weeks turned into months, and to his wife’s astonishment and dismay he never arrived or saw his family again. He had disappeared.

A mere eight months later Thomas Edison would unveil the “Kinetograph” to the world, claiming his apparatus to be the birth of the moving image, featuring “pure motion recorded and reproduced” for the first time. Recognizing the device as a version of one invented by her missing husband, Lizzie became convinced that Edison was behind Louis’s disappearance. She spent seven years trying to sue Edison (a legal technicality declared Le Prince “missing” and not officially deceased), but eventually Le Prince was to receive widespread public recognition as the real inventor.

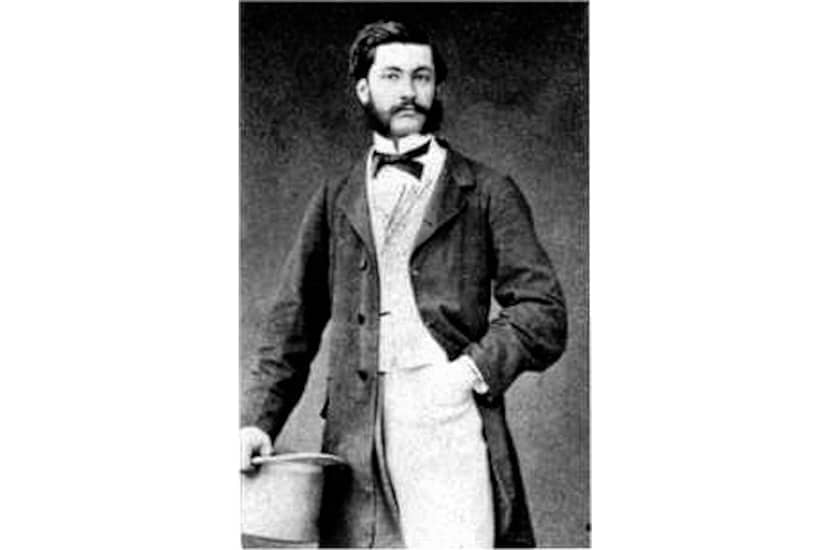

He was a bilingual, middle-class war veteran, an art critic and painter and a man who has affected more institutions in Leeds (where he made his breakthrough) than the River Aire. Paul Fischer adds vivid color as he chronicles his subject’s obsession with bringing the world’s first motion picture camera to market, and sketches the revolutionary backdrop to this story of transatlantic treachery.

We are reminded that this was a time of hitherto unparalleled technical and industrial innovation:

Louis and his brother were members of the first truly modern generation. Photography, telegraph, the steam engine and anesthesia all came into public use before they reached adulthood. The very concepts of labour, trade and leisure were transformed by new possibilities.

Fischer pinpoints key moments he believes were the impetus for Le Prince’s creation, such as meeting Louis Daguerre as a child or experiencing the Franco-Prussian war. Le Prince’s method of dealing with the effect of war on his psyche was, he suggests, the creation of his camera. The story contains light as well as shade. A spry humor is present in his account of how Le Prince once got arrested as a Prussian revolutionary on the grounds that he was holding a bouquet of red, white and blue flowers in the wrong crowd.

Woven in are stories of others who shared the goal of capturing life and eventually motion on film, and created innovations in still photography: Henri Desire Mont, who patented a twelve frames-per-second camera; Louis Ducos du Hauron, the pioneer of color photography; George Eastman, the inventor of photo negative film; and Eadweard Muybridge, the inventor of the camera shutter. All these men had slowly and often unknowingly been working towards the developments that Le Prince would bring together to create the world’s first motion picture camera — or “deliverer” as he called it. Fischer also gives his narrative the flavor of a whodunit, with chapters entitled “The Crime” and “A Gun that Kills Nothing.” This “true tale of obsession, murder and the movies” is an illuminating and thrilling read.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.