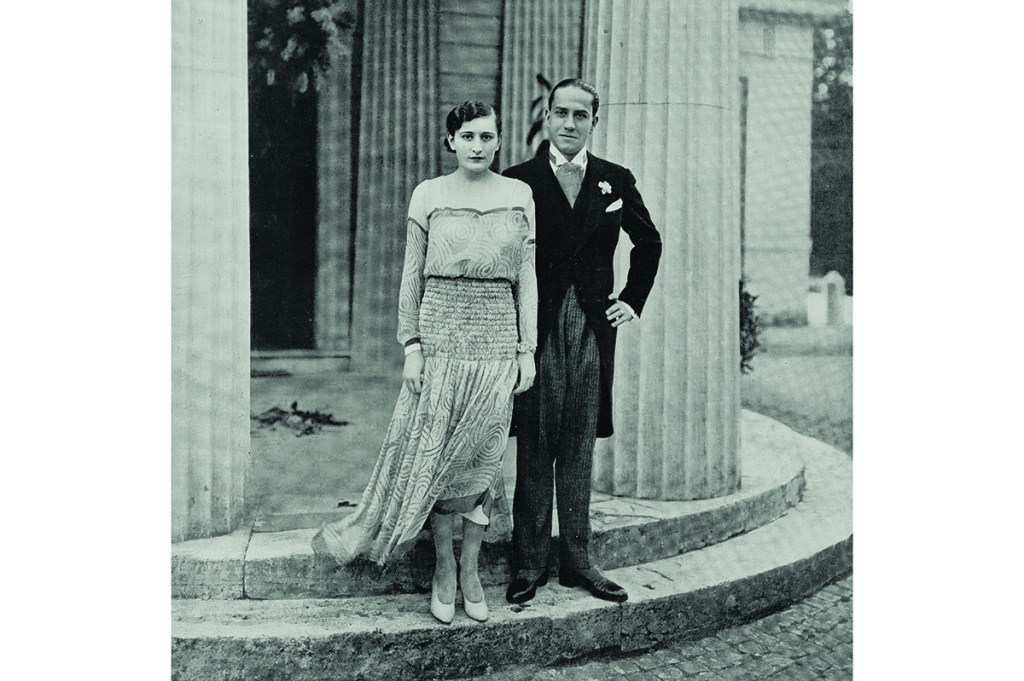

In April 1930, the nineteen-year-old Edda Mussolini married Count Galeazzo Ciano, aged twenty-seven, after a brief courtship in which love appears to have played little part. Her father, Il Duce, wanted the magnificent occasion to be not merely the wedding of the century but a grand, almost royal, demonstration of fascist might and a celebration of fecundity. Edda, his beloved firstborn, was to stand for everything that was best about fascist womanhood, while the groom was to carve out the path of “the new Italian man.” These were the glory years, and thousands of schoolchildren sent poems and cards with angels in advance of the occasion, which the Papal Nuncio attended with a present from the Pope.

But, as three cars set off for the honeymoon to Edda’s beloved Capri — one for the bridal couple, a second for Edda’s maids and luggage and a third for the bodyguards — she noticed a fourth. In it were her parents, Benito and Rachele. When Edda pulled over, she asked her father what on earth he was playing at; a sheepish Mussolini apparently insisted that he intended only to accompany his daughter some of the way and was just about to turn back. True or not, the action was, according to Caroline Moorehead in this riveting biography, indicative of how dependent on his daughter Mussolini had become, a mere five years into his role as Duce. He told his lover Angela Curti soon after this episode that Edda was definitely his favorite child (he had at least four more children) and that he considered his new son-in-law intelligent and a man who would go a long away on his own merits.

How this intense father-daughter love, as well as the eventual relationship between Edda and her husband Count Ciano, played out in the following fifteen years, against the backdrop of World War Two and the rise and fall of Italian fascism, makes for a compelling story which is much more than simply a biography of Edda. It is also a biography of her family, especially her father, whose intense admiration and need for his daughter’s approval never wavered. Mussolini felt closer to Edda as a confidante than he did to anyone else — not even his long-suffering wife, Rachele, or his many mistresses.

When, in December 1943, his protégé Ciano was in prison awaiting trial and likely execution, having turned against his father-in-law, Mussolini was concerned that Edda should understand that he was impotent to intervene. He knew that Ciano was by then hated by both Italian fascists and German occupiers, and that for reasons of state such plotters had to be killed if the Nazis were to be convinced of Mussolini’s own good faith.

Yet as Edda told her father during one of their stormy encounters at this time, it would take just two determined men to free her husband, words that were carried back by spies to Berlin. Even Hitler believed that Mussolini would never allow the father of his beloved grandchildren to be executed. Ciano wrote to his mother from prison that he never would have believed that Edda would have done so much for him. She had, in thirteen years of marriage, proved “an exceptional wife, an exceptional woman,” he wrote. Yet her efforts were to no avail. Ciano and four others were shot by firing squad on January 11, 1944, and the gruesome event was filmed by German officers.

Mussolini himself had effectively killed the husband of the child he loved, and Edda never forgave her father, whom she called Pontius Pilate in one of their final meetings.

In between these dramatic events, the wedding and the execution, Moorehead paints a vivid picture of an unusually complicated woman. Edda was “a delightful mixture of childishness, love of beauty, laziness, a dreamer” one minute and a poor mother and a rebellious adolescent the next. She was not beautiful but had an angular elegance and style that came close. According to a psychiatrist who had to write a report about her once she had escaped to Switzerland after her husband’s death, she was charming, thoughtful, considerate and kind. It was in a Swiss clinic that she learned of her father’s violent death, shot by partisans along with his mistress Claretta Petacci on April 28, 1945.

Despite now hating her father, she remained profoundly attached to him and affected by his death. She said later that on hearing of his death over the radio she had been unable to move and turned to stone. Doctors sedated her and put her to bed, and she recovered. Controlling her emotions was something she had learned as a child. As she said herself, it was just as well that she was a fighter since she was now, aged thirty-four, in charge of three young children. All of them were refugees and bore two names — Mussolini and Ciano — which both spelled danger. She had no idea if her mother and siblings were alive, nor where they were. Not surprisingly, she insisted from this point onwards, especially to the Americans interviewing her, that she had never been interested in politics and had always wanted only a peaceful life.

Edda had been a child when her father came to power, and she was only twenty when she moved to Shanghai, where her new husband was posted as consul. Both indulged in affairs. It was a shaky if exciting start to a marriage on the world stage, as Edda was sent as occasional emissary to Germany. But she matured during the war, most especially after training as a Red Cross nurse, when she found herself on a hospital ship bound for Greece that was torpedoed. As the ship keeled over, she jumped and was rescued after five hours clinging to a life raft. Her courage on this occasion was rewarded with a medal, but far more courageous was her dogged battle to secure her husband’s release and to ensure her own and her children’s escape to Switzerland. Never a natural mother, Edda craved action and found danger an antidote to boredom. Emergencies brought out the best in her.

The dramatic final chapters read like a fast-paced thriller as a genuinely distraught Edda fights with unexpected emotion, not only to save her husband and get her children to safety, but to face down her father. In another angry confrontation, she accused him of not understanding that the war was lost and Germany finished. In one outburst she was heard to shout at him that “if you were ever to kneel before me dying of thirst, I would pour out [the water] on the ground before your eyes.”

Edda probably would not have managed her own escape across the border without the help of Emilio Pucci, an Italian aristocrat and former lover who remained utterly devoted to her. As she traveled, she hid under her clothes a bundle of her husband’s secret diaries, which she had hoped to use as currency in exchange for his life. But, having delivered Edda to safety, Pucci failed to make his own getaway. He was arrested by Germans and taken to Verona where he endured hours of savage Gestapo torture in an attempt to find out if he knew where the Ciano papers were. He did not crack — his loyalty to Edda was apparently inexhaustible — which makes a poignant contrast to his inamorata’s relationship with her father. Eventually he was released and, after the war, reinvented himself as the designer whose brand of psychedelic silk dresses became a byword for luxury Italian fashion.

Moorehead draws on a vast array of sources, including interviews with grandchildren of the protagonists, and remains keenly aware that there are often conflicting versions of precisely what happened. Her book, compassionate but unflinching in the face of what is not always an edifying story, will surely become a standard account of the twenty-year fascist experiment in Italy. Its glamour, decadence and brutality are enhanced by seeing the overall story through the prism of its leading female player, a woman she finally — and persuasively — concludes had influence but no real power. Such, alas, has been the fate of countless women throughout the ages.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.