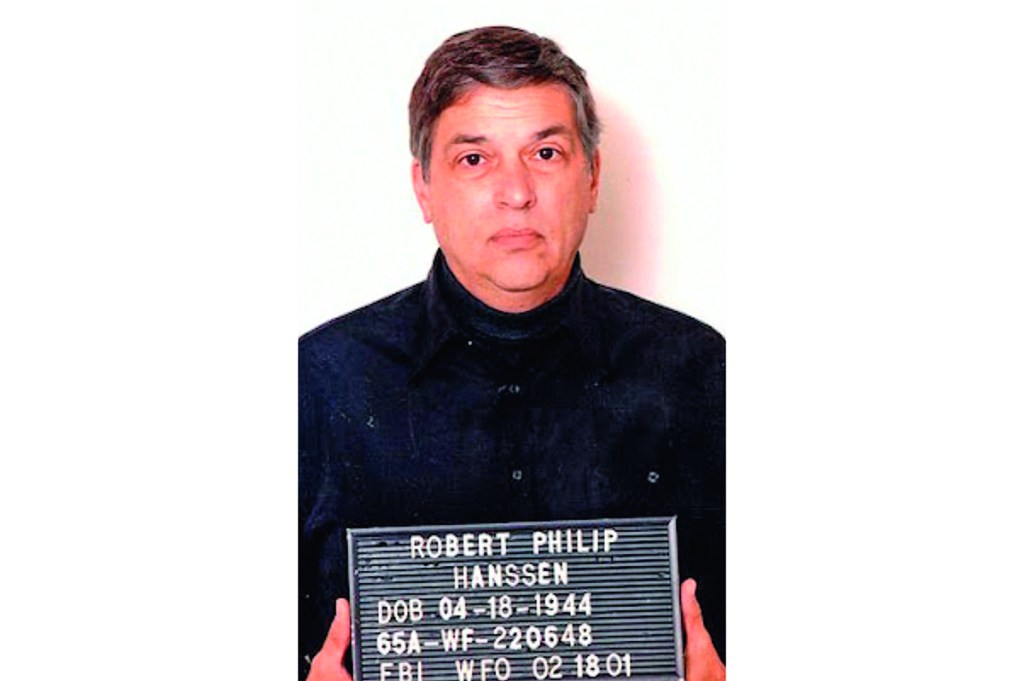

On one level, Lis Wiehl’s enthralling and grimly astonishing A Spy in Plain Sight is simply the story of Robert Hanssen, an FBI agent whose espionage activities were described by the Department of Justice as “possibly the worst intelligence disaster in US history,” a crowded field even at the time of his arrest in February 2001. “Over twenty-two years,” explained the DOJ in a 2002 report, Hanssen had “given the Soviet Union and Russia vast quantities of documents and computer diskettes filled with national security information of incalculable value.” And his betrayals had cost lives. Wiehl cites three (although there will have been more): each had been fingered as American agents by both Hanssen and Aldrich Ames, Hanssen’s predecessor as, in Wiehl’s description, “the most notorious spy in modern US history,” which gave the Soviets the corroboration they appear to have required.

All three were executed, but, according to Wiehl, one of them, Dmitri Polyakov, was dispatched in a particularly grotesque manner, with his last moments preserved on a video shown as a warning to later generations of KGB recruits: details, it must be said, missing from other accounts I have read. Of this trio, Polyakov, a general in the GRU (military intelligence) was the most important, not motivated by money, but, in the opinion of Wiehl and many others, a patriot who distrusted and disapproved of his country’s leadership. So useful was the material he provided that he may have been the best double agent the US ever had, although we can never know for sure.

Hanssen offered up Polyakov’s name early in his dealings with the KGB, and did so for $30,000, a bargain given his importance: Hanssen was new to the game. Nevertheless, in Wiehl’s view, Hanssen realized that Polyakov was “the one American asset placed highly enough in the Soviet intelligence services to uncover his identity.” Polyakov was transferred to a non-job. He later retired, but being exposed by Ames sealed his fate. Hanssen may have sold Polyakov too cheaply, but by eliminating the threat he could pose he “had protected his own market value immensely.”

Whether Hanssen had actually thought that through is, after reading this book, unclear. Part of the wider mystery is how talented a spy he really was. There can be no question that, in terms of the quantity and the quality of what he delivered, Hanssen was, for Moscow, hugely effective. But was he merely an opportunist who took advantage of the FBI’s astoundingly lackadaisical attitude as regards security, or was he an altogether more sophisticated operative, someone who had analyzed the dysfunction within the organization in this area and then exploited it to the full?

Hanssen’s jeering “what took you so long?” when eventually arrested may have been bravado, a touch of the 007 that some side of him yearned to be. Wiehl suggests it was an expression of his contempt for the FBI. If so, it could also be seen as a tacit admission that he was not so well-equipped for his second, undercover career as he may have liked to be.

For, when it came — to cite le Carré — to tradecraft, Hanssen contained multitudes of contradictions, sometimes careful, sometimes reckless. He, not the Soviets, set up the arrangements for the handover of information, and he concealed his identity from his new paymasters yet fruitlessly recommended they recruit his best friend, too. He illicitly hacked into colleagues’ computers to, he maintained, demonstrate their vulnerability (not the cleverest of cover stories, but, tellingly, it worked). On at least one occasion, he used an FBI telephone line to contact the KGB. It’s generally unwise for spies to stand out, but, however respectable his public profile, Hanssen did, and not in a good way. He was infamous at the office for, among other peculiarities, his poor social abilities, funereal dress sense (“Doctor Death”) and lack of discretion. And, oh yes, he once dragged a female subordinate down a hallway.

The contradictions didn’t stop there. He was a man of the Right who spied for the Soviets, a devout Christian (a member of Opus Dei, no less), fiercely pro-life but capable of reducing Polyakov to a tradable object destined for destruction. He was a churchgoer and a devotee of strip clubs. At one of the latter, he met a dancer with whom he entered into a strange and costly but barely consummated (or never-consummated, depending on whom you ask) relationship. Despite this and other more conventional infidelities, Hanssen never lost his attachment to his wife, however wrapped up in his need for control that attachment might have been. He secretly posted prurient stories about her, as well as revealing pictures, online. And unbeknown to her, he encouraged that same best friend to peer through the Hanssens’ bedroom window and watch them having sex. Wiehl doesn’t arrive at a definitive conclusion about what made Hanssen do what he did, or what made him tick, although I’m not convinced anyone could. It was not simply about money, although that always mattered. Instead, broadly speaking, she sketches out various possibilities (none of them ideological) — from thrill-seeking to a narcissistic desire to prove his own supposed superiority — and mainly leaves readers to come to their own decisions. That said, she is clearly sympathetic to the notion that a crucial part of the puzzle was what Hanssen’s psychiatrist described as his “extraordinary” ability to keep all those contradictory aspects of his life locked into separate compartments: “He pushed it to nearly as far as it could go.”

Where there can be no disagreement is the extent to which Hanssen was enabled by profound structural flaws within the FBI, another narrative running through A Spy in Plain Sight (the last three words in the title are something of a hint). In addition to its other merits, this book is an excellent — and cautionary — chronicle of organizational failure, worth reading by an audience beyond those interested in well-told tales of espionage or the Cold War.

The conviction that if there was another mole as damaging as the CIA’s Ames (who had been arrested in 1994) it could not be one of the Bureau’s own was perhaps not so unusual, but in this case it was taken to dismaying lengths. It was also reinforced by a strong culture of trust inside the FBI, which was both a strength “and, in the wrong circumstances, its Achilles’ heel.”

FBI offices were treated as secure spaces, with the result that sensitive information was left lying around, either in physical form or virtually, on standalone or networked computers. Hanssen, regarded as an IT whiz when most of his colleagues were not, had remarkable access to this information, at times legitimately, even if the use he made of it frequently was not.

The jobs he held at the Bureau over the years, many directly or indirectly connected to counterintelligence, were a rich source of material for Moscow, but it was easy for him to supplement that lode by nosing about. Making matters simpler still, there was little policing of what was removed from his workplace. When some of the FBI’s systems were upgraded, records of those who logged in could be audited, but this didn’t seem to be the protocol. Wiehl quotes from a report commenting that “the FBI lacked the ability to know what it knew.”

Thanks to the way that culture of trust intertwined with complacency and carelessness, clue after clue was overlooked or ignored. To take two examples — there are many more — Hanssen was caught photocopying documents he should not have had, and he was found installing password-busting software on his PC. It’s thus fitting that the key to Hanssen’s downfall was provided by an outsider, a former KGB officer who, for a price, supplied the evidence that unmasked the high-ranking mole for whom the FBI and CIA had been searching. Rather than confirming the guilt of the then-prime suspect, it brought Hanssen down.

In exchange for full cooperation and an admission of guilt, Hanssen was spared — if that’s the word — execution and sentenced to solitary confinement in a supermax prison for the rest of his life, compartmentalized for good. He lives there today, reportedly “almost catatonic,” although no one is certain if that too is a pose or real.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.