Life imitated art to a depressingly predictable degree when a clip from Todd Field’s Tár circulated online. It’s part of a scene where the film’s title character, superstar conductor Lydia Tár (played by Cate Blanchett), leads a masterclass at Juilliard. She haughtily dismisses students’ reluctance to learn the classical canon because of their difficulty “identifying” with its composers.

To some, Lydia’s monologue was a vindication: a righteous tirade against “wokeness.” To others, the speech exemplifies Lydia’s abuse of power, which includes not only dressing down students and mentees but sleeping with many of them and torpedoing their careers.

But oversimplified views of Lydia as a crusader or villain flatten the film’s wrenching complexities. The film certainly examines how mentorship can slide into coercive seduction; how powerful institutions protect their own. But Tár is more than a contemporary #MeToo story. Perhaps the film is arguing that powerful women can be “just as bad” as men in their abuse of power. But beyond this, Tár is a profoundly truthful look at how Lydia’s image as “one of the boys” prompts questions about how the love of beauty in art entwines uncomfortably with the pursuit of beautiful youth.

In that controversial Juilliard scene, Lydia does more than attack identity politics. She’s trying to pass on her love of the classics to convey the endless possibilities in the works of long-dead white men. But these are not the same thing. When she plays the piano, teasing out the complexities of Bach or speaking with awe of the “inevitability” of Beethoven, she is dazzling. In the scene, she archly refers to herself as a “U-Haul lesbian,” but in the film, her dandy-butch drag is a manifestation as an evangelical belief in classical music and its power to connect to audiences.

Lydia’s look calls back to male giants of conducting. In an early montage, Lydia is fitted for suits at an upscale boutique. It is a pornographic ode to fashion: perfectly starched collars, chalk outlines drawn on expensive grey wool, and the luxurious gesture of the tape measure wrapped around Lydia’s chest to get the perfect fit.

Afterward, we learn that these suits are a historical drag. She’s mimicking the looks of the great male conductors of a previous generation, like Claudio Abbado and her mentor, Leonard Bernstein. Bina Daigler, the film’s costume designer, modeled some of Lydia’s outfits on the high-neck cashmere sweaters and suits of Herbert von Karajan, one of the twentieth century’s greatest conductors (controversial due to his association with the Nazis). Lydia’s new clothes are for a new album cover — one that will mold her in the image of these male legends.

young lydia tár pic.twitter.com/VJhkxQzdQC

— be (@villanwve) November 27, 2022

There’s a depressing reading of Lydia’s style: can she only achieve greatness by literally stepping into the shoes of men who’ve come before her? But these clothes are also fetish objects, offerings to the dying god of classical music. If Lydia is unduly worshipped as a deity, it is because she herself is a worshipper, an ardent devotee and evangelist.

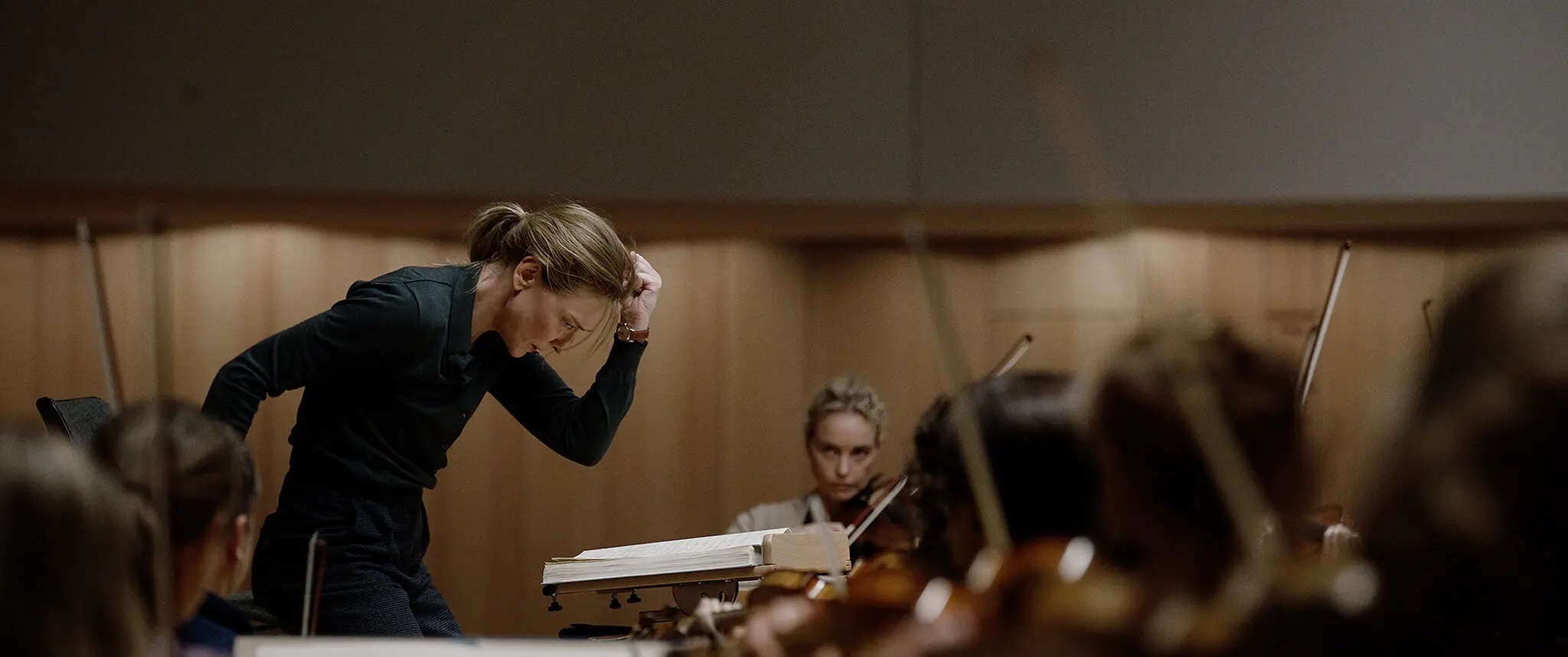

Tár centers around Lydia’s recording of Mahler’s Fifth symphony. It’s a titanic work, a symphony on steroids that pushes the form to its limits. Lydia praises the novelty and depth that Bernstein was able to find in Mahler. “He would often play with the form,” she says, because “he wanted an orchestra to feel that they had never seen, let alone heard or performed, any of that music.” Her sense of the ability of the great conductor to reveal the new and sublime in the classical canon sounds like a seduction of the orchestra; the good conductor leads them “on the most extraordinary tour of pleasures.” We see Lydia’s seductive powers in the rehearsal scenes.

As she develops her take on Mahler’s Fifth, Lydia fleetingly references film director Luchino’s Visconti, who uses the symphony in his film Death in Venice. She’s saying that remembering the film means that a player knows the music “too well” to reimagine it. But she really means that to know Death in Venice “too well” exposes her vices and frailties. In Visconti’s film, the conductor and composer Aschenbach (a character modeled on Mahler) develops a paralyzing obsession with a beautiful young boy.

At first, this fascination is purely aesthetic. Aschenbach has always believed that true beauty comes from creative human endeavor. He’s shaken by the Botticelli-esque boy Tadzio, whose beauty has sprung spontaneously from nature. The film languorously tracks Aschenbach’s voyeuristic gazes, accompanied by the swelling music of the Fifth. The lines between aesthetic veneration and unspeakable desire blur, and the audience must confront the darkness that can come from worshipping beauty.

Aschenbach desires from a distance, pathetically tracking the steps of his love object until he finally dies in convulsions as Tadzio frolics in the sea. The decadence of Ashenbach’s longings was, for Visconti, a search for symptoms: he looked back on turn-of-century high culture to see how it descended into the barbarism of two world wars. Lydia’s shameless and ultimately futile pursuit of her desires is bound up in the decline of high culture itself. Her young and beautiful girl of the moment — an angelically lovely cellist — is indifferent to Lydia both sexually and artistically. The cellist has discovered her favorite piece on YouTube (bypassing the usual gatekeepers of the classical world). She doesn’t even remember who conducted the performance, denying the conductor’s role as the supreme authority. Lydia is losing her touch not only in seduction but also in gaining new devotees with her fiery evangelism.

As her sins come to light, Lydia clings to the talismans of the great male conductors that are her idols. When she maniacally tries to hijack the conductor’s podium during the performance of the Fifth, she wears a disheveled tux and tails — a mad, rumpled Mahler fighting for her terrain. When Lydia, disgraced, returns to her childhood home, she comforts herself by watching old tapes of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts.

These were perhaps one of the last successful attempts to foster classical music appreciation in a younger generation. In her exile, she is put in service of a younger generation’s new idols as she plays video game scores for an audience of cosplayers. A new kind of musical drag topples her old gods and, with them, her fraught ideals of music and what she could make it do.