The world described in this book is weird enough anyway, but reading about it during lockdown is positively surreal. It’s about VIP nightclubs, mainly in New York, but also in Miami, Cannes, St Tropez or wherever rich people congregate. Ashley Mears is a professor of sociology, as she likes to remind us with references to Bourdieu, Durkheim, Veblen, etc, but mainly she is a very good reporter. The reason she was allowed into the VIP clubs is that she used to be a model and can still pass as one, though actually too old for admission (at 31) by most club standards. But it amused some of the promoters to have a professor who looked like a model taking an interest in their work.

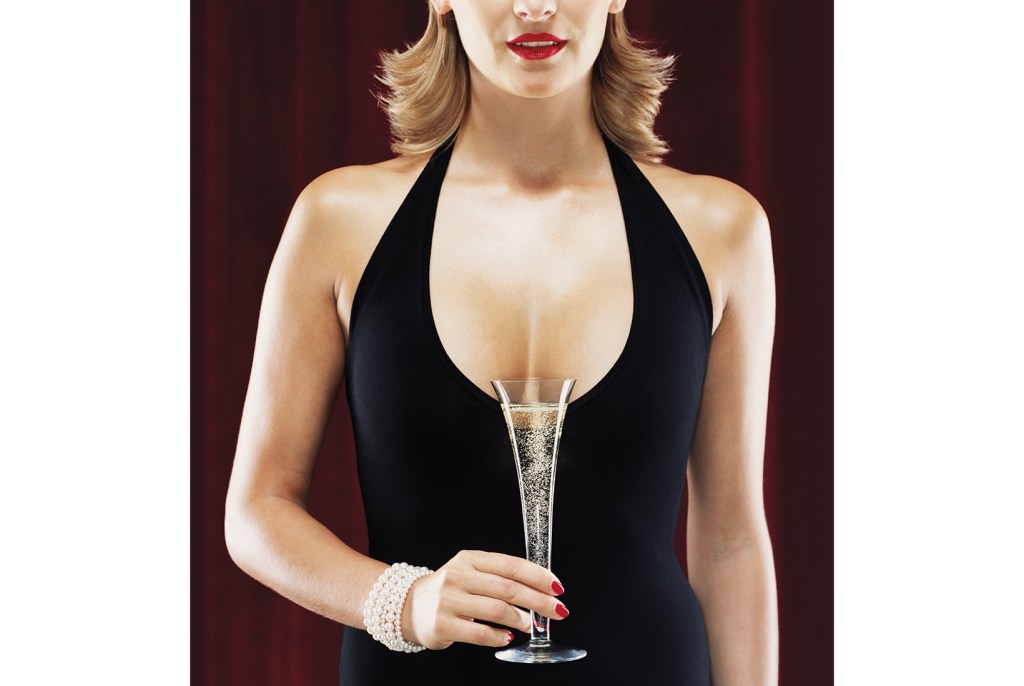

Some definitions first. A VIP club is one where rich men, usually white, almost invariably heterosexual, can rent a table for the night (at a cost of up to $30,000) to impress their friends, and order ‘bottle service’. This means processions of ‘bottle girls’ bringing vastly overpriced bottles, usually of champagne or vodka, lit by sparklers — though in one Los Angeles club the bottle girls are replaced by ‘flying midgets’ on aerial cables. When a customer orders a particularly large or expensive bottle (say a methuselah of Cristal at $40,000 or a jeroboam of Dom Perignon), the DJ will sometimes interrupt the music to say ‘Alex from London is in the house and has just spent $100,000 on Dom’ and turn a spotlight on him.

According to Mears, this particular type of club started in New York in the late 1990s and really took off in the 2000s. The status of the club is defined by the beauty of its ‘girls’. The girls are not there to offer sexual favors (they would be thrown out if they did); they are only there by way of set dressing. The best are fashion models, thin, elegantly dressed, and more than six foot tall in their high heels, but occasionally a club promoter will let a ‘good civilian’ in, if she is tall and pretty enough. The girls never have to pay for anything. They get their meals, drinks and sometimes short-stay accommodation or air tickets for free, but no actual cash, apart from occasional cab fares, because then they feel ‘it’s like work’. Outsiders often think the promoters are pimps, but they aren’t; sex is not part of the transaction. Many of the customers don’t even talk to the girls; they just like having them around.

It is the job of ‘image promoters’ to rustle up a constant supply of beautiful girls, and these promoters are paid up to $3,500 a week for doing it. It is hard work, spending all day phoning contacts and hanging around outside model agencies and places where models congregate, such as a Pinkberry frozen yoghurt shop, trying to persuade girls to come to their clubs and then keeping them there till 3 a.m. If they leave any earlier they are guilty of ‘dine and dash’ and not asked again. The irony is that the promoters often don’t fancy the girls themselves — they find fashion models too skinny — but they know what the clubs like. Anyway the doormen reject any who don’t come up to scratch. Promoters and their girls are given free tables next to paying customers.

Mears interviewed 44 promoters and says the interesting thing is that all except one fell into the job by accident. They happened to take a couple of beautiful girls to a club and were told that if they could regularly bring more of that standard, they would be paid a fee as well as getting free drinks. One Jamaican promoter, Michel, remembers his shock at hearing the offer. He was only 19, working as a busboy in a Miami café and hanging out with his cousin at a dive bar where the owner told him: ‘People just love you guys. Have you ever thought of being promoters?’ Michel had no idea what that meant, but when it was explained to him his incredulous reaction was: ‘You mean that I can get paid for doing what I’m already doing for free?’ Which is precisely what happened.

[special_offer]

Most of the promoters are immigrants and ‘ethnically diverse’. Mears only came across eight white American promoters. A surprisingly large number are black, although their girls, and the clubs’ customers, are almost uniformly white. But black promoters are seen as ‘cool’, and girls, especially eastern European girls, are attracted to them because they think (wrongly in most cases) that they can provide drugs. Dre, a very popular black promoter, told Mears he wouldn’t even be allowed into the clubs if he didn’t bring the girls. Dre is rare in that he is pushing 40 — most promoters have moved on by then. It is not a country for old men.

The very biggest spenders are called ‘whales’ and can easily spend $100,000 in an evening. But whales don’t come that often; it’s the ‘mooks’ — fund managers, bankers, cosmetic dentists — who form the mainstay of the clientele. They tend to work very hard in their day jobs, so they believe they’re entitled to play hard in the evenings — by drinking champagne in the company of beautiful girls and spending lots of money.

This is part of a recent trend for ‘luxury experiences’. In the past the working rich tended to go for objects — art, watches, wine — that served as status signifiers while also holding their value or even appreciating. But luxury experiences — spraying champagne round VIP clubs — are just demonstrations of waste, or ‘a ritualized form of wealth destruction’, which Mears compares to the potlatch ceremonies described by anthropologists in 19th-century Canada. ‘It takes considerable co-ordinated effort to mobilize people into what looks like the spontaneous waste of money,’ she notes drily, ‘and the VIP club has mastered it.’ But will the clubs ever return after lockdown? Or has Mears recorded the last bonfire of the vanities? Either way, it’s a fascinating read.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.