One of the great achievements of Spanish art is in its use of black. No other national school harnessed the dark arts to such effect. In Spanish painting, the color black might convey shadow, or the mystery of the unseen, while at the same time presenting a brooding presence, a dark mass right there on the surface.

Just look at “Las Meninas,” Diego Velázquez’s masterpiece of 1656. Now consider the subject. Is it the five-year-old infanta? Her ladies in waiting, the “Meninas” of the title? The painter portrayed at his easel? The infanta’s royal parents in the reflection of a mirror? Some unseen viewer interrupting this tableau? I might suggest that the darkness, obscuring most of the picture, surrounding and pressing on the fragments of light that barely hold this composition together, is as much a subject as anything else. The blackness draws us in, not through what it depicts, but by what it obscures.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) was the son of American expatriates. Born in Florence, he was educated in Paris and lived the majority of his working career in London. But he went back to black more than once, through his extensive study of Spanish painting and a lifelong fascination with Spanish culture. The underlying thesis of Sargent and Spain, a major exhibition at Washington’s National Gallery of Art — opening this October and on view to January 2023, later traveling to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco — is that the painter’s many passages through Spain not only gave him his subject matter but also informed his painterly style. For anyone who has wondered about Sargent’s Spanish affinities, this exhibition reconstructs those sojourns and looks to the sources of his synthetic Spanish vision.

Hispanophilia permeated the Romantic nineteenth century. Spain presented itself as a “country untroubled by modern life, with a profound sense of the austere — melancholic and sacred, timeless or at least premodern,” write Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond in the exhibition’s illuminating catalog. “Spain became a locus for this Romantic sensibility and an imagined Iberian past was, in part, created to satisfy it.”

In the industrializing culture of the West, books such as Washington Irving’s Tales of the Alhambra (1832); George Borrow’s Zincali, or, An Account of the Gypsies of Spain (1841) and his Bible in Spain (1843); Théophile Gautier’s Voyage en Espagne (1845); and Richard Ford’s Handbook for Travellers in Spain (1845) all set the mood of this nostalgic Spanish vision. Victor Hugo’s Hernani (1830) and Georges Bizet’s Carmen (1875) famously brought the romance of Spain to the modern stage.

But for the painters of the nineteenth century, Velázquez was their modelo ideal. A pilgrimage to study and copy his paintings in Madrid at the Prado became a must. From 1879 through 1912, Sargent made seven extended visits to Spain. The Prado was his first stop. According to the museum’s copyist register, Sargent here drew nine works by Velázquez and one by Ribera. As with Manet, who had made a similar visit to Spain some fourteen years earlier, Velázquez “exerted a lasting influence on his portraiture,” write Kilmurray and Ormond. Further influenced by his painting teachers Carolus-Duran and Léon Bonnat, both followers of the seventeenth-century Spanish master, Sargent was soon said to be “Velázquez come to life again.”

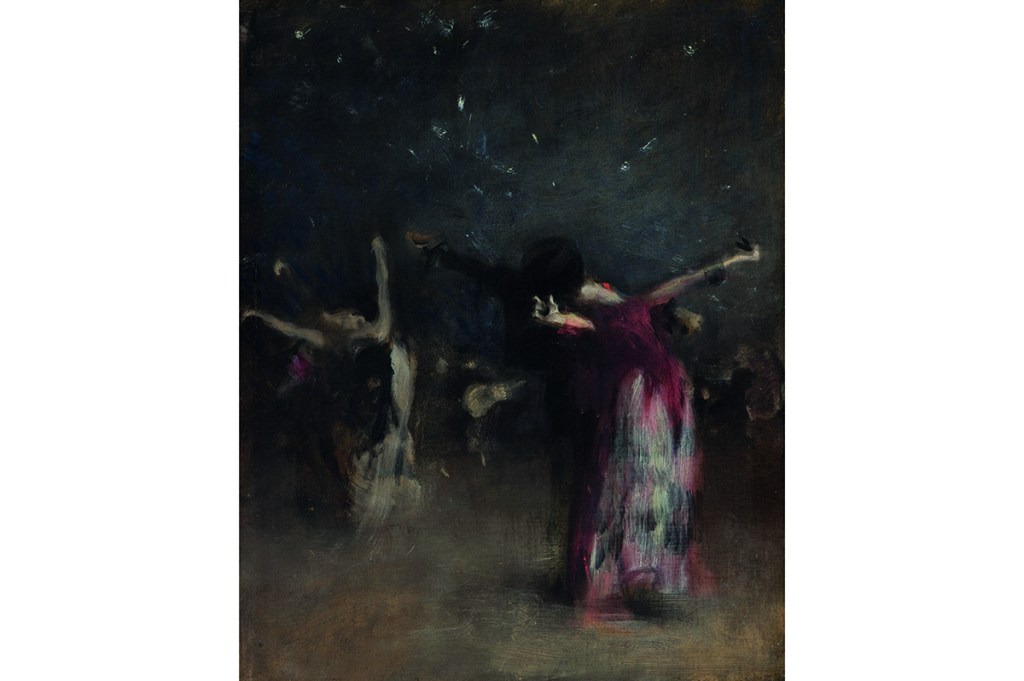

Curated by Sarah Cash, the associate curator of American and British Paintings at the National Gallery of Art, along with Kilmurray and Ormond, who authored the artist’s catalog raisonné, Sargent and Spain brings together 140 examples of the artist’s oils, watercolors, drawings and photographs, starting with the artist’s youthful dives into the Spanish darkness. In its haunting forms, his early “Spanish Dance” of 1879-82, here on loan, seems so Iberian in style that it represents one of the rare examples of a work not made by a Spaniard in the collection of New York’s Hispanic Society.

In 1882 Sargent brought together his many Spanish studies to compose his breakthrough oil “El Jaleo.” Now in the collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the painting of an up-lit flamenco dancer did not travel from Boston, but its many studies are here on loan from the Gardner. Due to its ambitious size and revealing subject matter, the painting proved to be the sensation of the 1882 Paris Salon. The artist became “the most talked-about painter in Paris,” according to a contemporary account on “The Salon — From an Englishman’s Point of View.”

It is remarkable to consider that this most Spanish of images was painted in Paris by an Italian-born American with a model “who was neither Spanish nor a dancer,” notes the art historian Nancy G. Heller in the catalog. “Nothing could be less spontaneous than ‘El Jaleo,’ but Sargent makes us believe that we are witnessing an actual performance.”

The painting is alive with a rhythm that extends through the very fingertips of its alluring, slanting, pose-striking dancer. It helps that Sargent was himself a supremely talented musician. As part of his international and idiosyncratic upbringing, Sargent had studied Italian folk music in Florence and could play the mandolin, guitar, banjo and piano. There’s a deep musical knowledge embedded in Sargent’s brushstrokes, which ring like sonic vibrations, plucked and strummed to virtuosic perfection on canvas.

Although its subject left few written records, Sargent and Spain reconstructs the artist’s itineraries through his extensive creative output — which ultimately totaled some 225 Spanish-themed works along with sketchbooks, notebooks and the two hundred photographs he collected (and possibly snapped himself). Over thirty years Sargent covered nearly every corner of the country — from Camprodon and Santiago de Compostela in the north to Seville and Granada in the South, and what seems like most points in between. Along the way he collected architectural images of Madrid, Toledo, Córdoba, Salamanca, León, Tarragona and Granada. The exhibition curators have for the first time also identified photographs of Sargent himself working and traveling in Spain.

Sargent brought the lessons of this Spanish class even to paintings that seem far removed from the Iberian peninsula. Consider his “Daughters of Edward Darley Boit.” This masterpiece of 1882, now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (and regrettably absent from the current exhibition), was a commission he painted in Paris of the four daughters of a fellow expatriate artist. The subject matter says nothing of Spain, but the multi-centered composition with its dark figures in profile is a homage to “Las Meninas.” Just look to its “evocative shadows,” note Kilmurray and Ormond, “the complex relationships between artist, figures, and viewer.”

Writing in the October 1887 issue of Harper’s magazine, Henry James offers the final word on Sargent and Spain: “Mr. Sargent had spent several months in Spain, and here, even more than he had already been, the great Velázquez became the god of his idolatry… It is evident that Mr. Sargent fell on his knees, and that in this attitude he passed characteristic a considerable part of his sojourn in Spain.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2022 World edition.