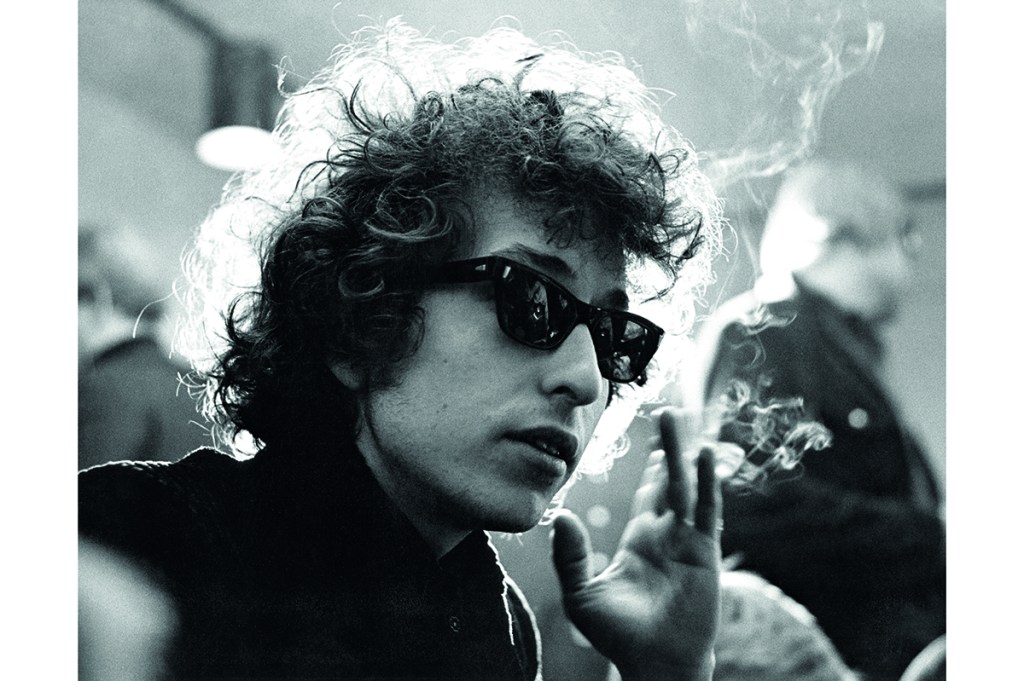

In Folk Music, Greil Marcus has captured an entire world of the creative and cultural development of the artist known as Bob Dylan in a single book. Marcus not only tells a Bob Dylan biography through the study of seven songs, he also creates an autobiography of his own long career as a writer on music and America — as well as a rich history of American folk songs and the new life they engendered as Dylan sat down to write his own. How does Marcus do it? I’ve often wondered as I’ve read him in the past. This time, I have no answers at all, only admiration and respect.

It is far from unusual for other biographies of Dylan — and there are a shelfful — to tell you more about the biographers than their subject. Writers like Howard Sounes and Bob Spitz have focused on revealing details of Dylan’s eventful personal life. Sean Wilentz’s Bob Dylan in America, which zooms in on key moments in Dylan’s creative process, and Richard Thomas’s Why Bob Dylan Matters, with its close readings of his songs, are both invaluable books for Dylan students and admirers. But Marcus ranges more widely, and his in-depth analysis of the songs themselves is unmatched.

His cultural knowledge of American history and music spans the seventy-seven years of his life, and many centuries before, too, from sea shanties sung by English sailors as they made for the New World, to Highland ballads given new life and instrumentation on the stone and plank cabin porches of Appalachia. Marcus’s knowledge of the music from which Dylan’s work springs is vast, and he wields that knowledge without pretense or condescension.

His passionate intensity can be off-putting to readers, or so some critics have complained for sixty years. I tend to revel in it, and never more than in this book, which is a perfect storm of things to love: American history, music history, Bob Dylan’s music and beautiful writing. Marcus’s style in Folk Music is colloquial but not informal, informative but not didactic, and downright seductive to follow. One might easily become repetitive in writing about the Dylan songbook, but Marcus keeps things fresh. He points out connections, certainly, but also the idiosyncrasies that set individual songs apart, lifting them into sharp and well-reasoned relief. The cover and thoughtful interior illustrations by Max Clarke complement Marcus’s, and Dylan’s, words with bite and flair.

The seven songs are, in Marcus’s order, “Blowin’ in the Wind” (1962), “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” (1964), “Ain’t Talkin’” (2006), “The Times They Are A-Changin’” (1964), “Desolation Row” (1965), “Jim Jones” (1992), and “Murder Most Foul” (2020). Prefacing these seven is a concise two-page biography of Dylan and a companion piece entitled “In Other Lives.” “I can see myself in others,” Bob Dylan said in Rome in 2001, speaking to a crowd of journalists. If there is a key to his work from now back to its beginning, that may be it.

Those well-used conditionals, “if” and “may be,” are doing a lot of work here, but it’s all good. Dylan lives the lives of not only the songs he’s written, but those he’s learned from others and performed for nearly seventy years. This spirit shapes Marcus’s “attempt at a biography made up of songs and public gestures,” in “a frame of reference, a source of life for certain songs… But never a key to their meaning.” Keys lock you in. Marcus cannot do that to Dylan. It’s good that this book does not follow a chronological order, because Dylan doesn’t. Marcus gets that, and relishes it.

A longtime New Yorker, Marcus is particularly attuned to Dylan’s time in Greenwich Village and to the musicians he encountered and learned from there. For instance, the dark life of the immensely gifted Karen Dalton is well and sensitively told. Interviews with Happy Traum, such a crucial figure on the Village folk scene, and still living and recording and performing in Woodstock, add a great deal. A spectacular chapter uncovers how Dylan translates the old prisoner’s lament of “Jim Jones” in performance.

“Blowin’ In the Wind” is one of Dylan’s best known and best loved songs. He, a small group of musicians and T Bone Burnett recently turned it into a one-of-a-kind recording that sold at Sotheby’s for nearly $2 million. Written in 1962, when Dylan was twenty-one, the song could be said to be part of the writer’s juvenilia, except for the fact that Dylan emerged fully formed from the artistic womb. The song, Marcus tells us, has its roots in the American Civil War anthem “No More Auction Block,” particularly as it was recorded by Odetta in her 1960 Carnegie Hall performance.

The Civil War underlies much of Folk Music, and that’s as it should be. We acknowledge the war’s importance in American historical memory, yet Marcus is the first to recognize and explore its importance to Dylan specifically. Also present are Malcolm X and Robert Johnson; Woody Guthrie and the Greenwich Village coffeehouses; and artist and writer Susan Rotolo, Dylan’s partner at the time, the woman hugging his arm as they walk down a wintry Jones Street on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963). Marcus’s exploration of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” the lead number on that record, is essential in setting the scene for the rest of the biography to come, a nourishing Brunswick stew of things you’ve heard before, brand-new stories, tales of times gone by and connections to later and to today. “There are no straight lines in the language songs speak” is a sentence I will always wish I had written.

Much of the power of Marcus’s own storytelling is in the histories and songs that underlie each work he discusses. You get two, or ten, for the price of one. He can talk about Old Dan Tucker on one page, and Machiavelli and Ovid on the next, and be consistently right about the influences on Dylan.

Quotations from Dylan’s rare interviews — or from his fauxtobiography Chronicles: Vol. 1 (2004), in which he speaks about the composition of a song — act as valuable connecting thread. Marcus’s chapter on “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” one of Dylan’s most powerful songs, reminds us what America was like in 1963, when the wealthy William Devereux Zantzinger, twenty-four, hit Carroll, fifty-four, with a toy cane at a Baltimore society gathering, causing her death — for which he received a six-month sentence.

Marcus is excellent on the strange and thrilling way “songs come loose from their authors” and “mark history, or even make it, but become part of its fabric, or part of the flag.” His discussion of “The Times They Are A-Changin’” in the context of the riot at the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, is brief and hard as a slap in the face.

Folk Music’s chapter on “Murder Most Foul” is the best thing yet written on this astounding new ballad, the only song from Dylan’s most recent record Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020) that he hasn’t yet performed live. Here’s how Marcus describes listening to it for the first time: “This was all a testament to the first fact of the song: the strange way that it can hardly be heard once without sparking anyone’s need to hear it again — a world gathering around a campfire of unanswerable questions, and it takes everyone around the campfire to hear the whole song.”

The last line of Folk Music made me gasp out loud, the first time a book has done that since I read The Grapes of Wrath at the age of twelve. But, in truth, the entirety of this powerful and accomplished book produces a similarly visceral reaction. There may never be a definitive Bob Dylan biography, but this quicksilver and mischievously informed sprint through the songs could be the book that does its mercurial subject full credit.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2022 World edition.