When Trojan Records attempted to break into the United States music market in the early 1970s, it hit an insurmountable barrier: the company shared its name with America’s most popular brand of condom. ‘It was a case of commercial coitus interruptus,’ says Rob Bell, at the time the label’s production manager.

In America, Trojan signified rubber, not vinyl. The label proved to have greater staying power in the UK, where it was at the forefront of popularizing Jamaican music. Founded in 1968 as a joint venture between Chris Blackwell’s Island Records and Lee Gopthal’s Beat & Commercial, from a Willesden warehouse Trojan introduced the music of Desmond Dekker, Lee Perry, the Pioneers, the Maytals, Bob Marley, Prince Buster and Jimmy Cliff to the British masses.

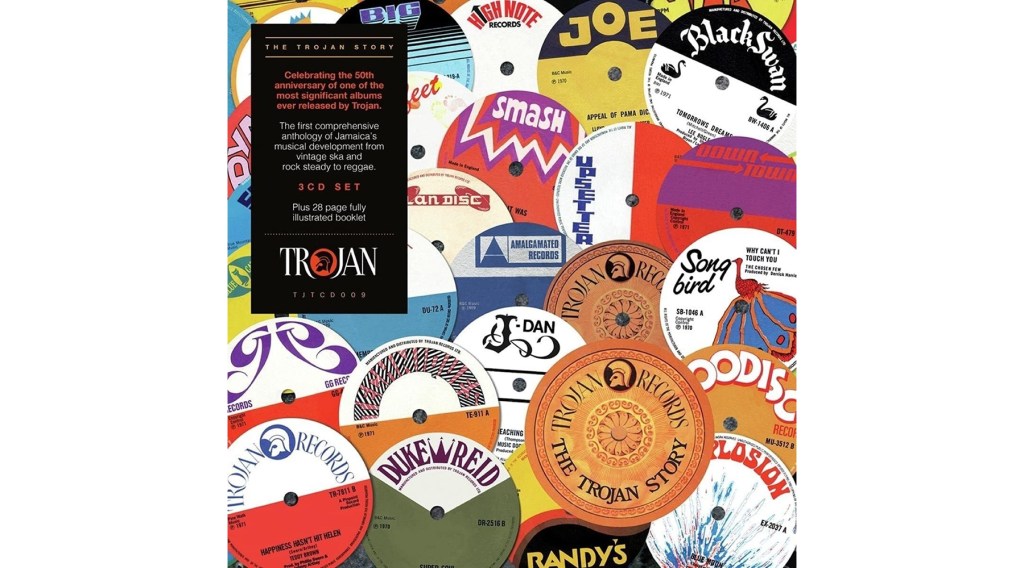

Its lasting legacy is The Trojan Story, the first and finest anthology of early ska, rocksteady and reggae. The 50 tracks form a compelling narrative, charting the evolution of Jamaican music through the 1960s while tracing its assimilation into British culture.

Initially, Trojan targeted Britain’s Afro-Caribbean communities. ‘It was a popular saying in the office that the average Jamaican family included enough money in their household budget each week for at least one single,’ says Bell. Trojan had licensing agreements with several Jamaican labels, but sometimes they had to improvise. Word would arrive that a record was proving popular on the island’s sound systems, pushing demand among Britain’s West Indian population. Trojan would race to secure the UK rights and rush-release the song.

By the time the label scored its first British no. 1 single in 1971 with the mighty ‘Double Barrel’ by Dave and Ansell Collins, something had changed. You don’t get to number one by selling to one relatively small demographic.

‘It was interesting how reggae crossed over to the white market,’ says Bell. ‘Some of it was a reaction to the more mainstream pop music, which was becoming a bit self-conscious and arty. Reggae was like R&B. It was soulful, emotional and really good to dance to. It was very popular in the clubs, and white kids started liking it more and more.’ For aficionados, affiliated to mod and skinhead fashion, an appreciation of the finer points of ska and reggae carried a certain cachet. As Bell puts it: ‘You had to know what you were talking about in this club.’

The Trojan Story was perhaps Jamaican music’s first concerted play to a white, album-orientated audience. Released in 1971, a year before the soundtrack to Jimmy Cliff’s rude boy movie, The Harder They Come, and two years before the Wailers’ breakthrough album, Catch A Fire, it was dreamed up by Bell, assisted by colleagues Dandy Livingstone, Webster Shrowder and Joe Sinclair.

‘I was getting really annoyed by the attitude of the mainstream media,’ he says. ‘We had records in the charts that were popular and artistically valid, and you would hear these stupid idiots saying, “It all sounds the same.” Ridiculous. It was a bit like how people spoke about rock ’n’ roll in the 1950s. The idea was to put together something that treated the music in a more serious way; not necessarily reverential. I tried to compile it in a vaguely cohesive manner, showing how rapidly the music had evolved from mainly copying R&B, into ska, with lots of jazz influences, then into rocksteady and reggae — all over the course of a few years.’

Fifty years later, its three discs remain the most accessible entry point into early Jamaican music. ‘It has done what it was supposed to do,’ says Bell. ‘It’s all there: take what you need.’ It also, in subtext, exposed the iniquities of the Jamaican music industry, where producers such as Perry, Byron Lee, Duke Reid, Bunny Lee and Leslie Kong ran the labels and held all the power. Beyond the headline names, few of the acts on Trojan made much money. ‘It’s hard to explain how unfair and cut-throat it was,’ says Bell. ‘It was total anarchy, really. The publishing was a mess. The saddest thing was that the artists were caught in the middle between producers who had them signed on crummy record deals, which were out of our hands.’

Bell tells a story that sums up the Wild West ethos of those days. ‘Bunny Lee would come over to London and be in our office Monday morning with a bunch of tapes. We’d do a deal with him for a couple of records for release on Friday. Friday would come along and Palmer Records, just up the road from us in Harlesden, would put out the same record! Bunny would have left our place with his deal, gone up to Palmer and sold them copies of the same tapes, got on the plane back to Jamaica, and us and Palmer would be yelling at each other on the Friday. We did our utmost to bring some order to it, but I don’t know how successful we really were.’

The reissued The Trojan Story is out now. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.