Tony Tetro’s memoir starts with a bang — or, rather, a bust. On April 18, 1989, twenty-five policemen spilled into his condo in Claremont, California, confiscated the $8,000 he had just been paid in cash and proceeded to search the place, slicing through wallpaper, pulling up carpets and emptying drawers. The scene is pacy, thrilling, a bit silly. It reads like a Hollywood film script; which, if I’m being cynical, is probably the point. The pièce de résistance:

If you pressed #* on the cordless phone, a full-length mirror would pop open and reveal my secret stash of special papers, pigments, collector stamps, light tables, vintage typewriters, certificates of authenticity, notebooks with signatures — everything a professional art forger might need.

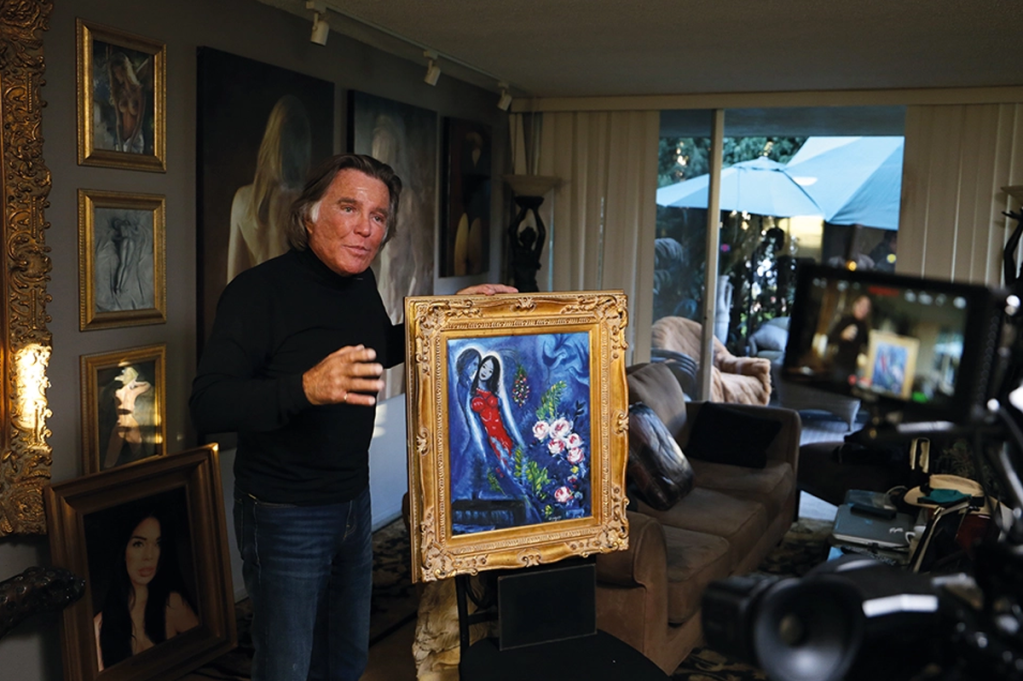

You needn’t have heard of Tetro to enjoy this book. Nor is any prior knowledge of the art world required. With all the cocaine and the fast cars, Con/Artist has more than a whiff of bad boy memoir about it, and the chapter titles (“The Last Laugh,” “The Wild West,” “Things Go Bad”) read like the names of pop songs. But beneath the grit and the glamour is a fascinating tale of a diligent, self-taught artist with a good work ethic and a great natural talent. Co-authored with Giampiero Ambrosi, the investigative journalist involved in uncovering Tetro’s connection to the Prince Charles art forgery scandal in 2019, this is the story of his life and art.

He was born Anthony Gene Tetro in 1950 in Fulton, New York, an all-American town not far from Lake Ontario, to Italian immigrant parents getting on with “getting ahead.” Spending his time building and decorating sandcastles at Fair Haven Beach, and copying photos from books and magazines, he showed an interest in art from a young age. In high school a favorite teacher introduced him to the Old Masters, whose paintings he pored over in the library. He remembers reading that when Michelangelo heard others say that the Pietà had been made by one of his rivals, he snuck into the Vatican, outraged, and carved his name on it. “I don’t blame him,” writes Tetro. “It’s ironic considering what I do, but years later when I forged a piece that somebody else claimed, I think I understood what Michelangelo must have felt.”

After his girlfriend got pregnant, Tetro and his young family moved to California. He sold furniture six days a week and, for fun, stayed up at night painting meticulous copies of Rembrandt, Picasso and Renoir — “letting my mind run with the flowing colors and brushstrokes.” The relationship didn’t last, but Tetro’s love of art did. It’s evident in the description of his first trip to a museum — the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) — to see a Rembrandt: “I remember an oval portrait of a man, and what struck me was that you could see he had a twinkle in his eye that looked so real and alive that he seemed to have a soul.”

After trying and failing to sell his work, Tetro stumbled on a copy of Clifford Irving’s Fake! at the supermarket and was inspired by the story of the Hungarian art forger Elmyr de Hory. “As I read, one idea became clearer and clearer: the only thing I could think was ‘I could do this.’” He took it slowly, knowing that an oil painting by a big-name artist would draw attention, and that provenance could pose a problem. So the first piece of art that Tetro forged was itself intended to be a fake: a small self-portrait of Chagall signed by de Hory.

A magician never reveals his secrets, but Tetro is no magician. Readers hankering for the nitty gritty of how he made his fakes won’t be disappointed. He recalls taking trips to Paris and Rome to pick up supplies: oils for Dalí, Chagall and Picasso; iron gall ink, a natural black that couldn’t be dated; antique books with empty pages that could be used for drawings. In order to give “just the lightest patina of age” to a Míro oil painting, he squashed the butts of Lucky Strike unfiltered cigarettes in a small glass of cold coffee, put the mixture through a strainer and then gently misted it onto the stretcher bars and the back of the canvas.

My favorite anecdote begins:

I knew a guy who had a restaurant. At night, when the restaurant was closed and everybody had gone home, he let me in and I stuck my painting, stretcher bars and all, into the wide-mouthed pizza oven, setting it at the lowest temperature, 140 degrees.

For a week Tetro baked this painting — his version of a Caravaggio — then he rolled it up and was pleased to see a spidery network of tiny white lines form across the surface. “Now, with the paint cracked, I set about creating a past life for the Bacchus using layers of grime, soot and varnish to suggest a history of age and neglect.”

Because that’s the thing, writes Tetro:

Ask 100 people what they think an art forger does and ninety-nine will tell you they copy paintings. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth… To really make a forgery, you have to make something new that never existed and give it a reason for being born.

Back in the 1980s, art historians still had a lot to learn about the high priest of the Italian baroque. In Tetro’s words, old books on Caravaggio were rare and facts were easily fudged. There was a chaotic period of Caravaggio’s life in Malta, and talk of paintings being lost, looted and destroyed. “In my mind, it all started to come together.”

I could have done without the passages on Tetro’s love interests and the lackluster later chapters when “life didn’t seem fun and vibrant anymore.” But from start to finish Tetro’s passion for art and his knack for drama carry the reader through. As for what’s real and what’s fake, who knows? Tetro writes:

If you think about it, the key to being a great forger is not being a great painter but rather a convincing storyteller. Like the best con artists, you must create a context and a backstory that justify an otherwise unbelievable circumstance.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.