My November was bookended by two characteristic displays of grace. I ushered it in by falling on all fours while out for a run, skinning both knees and demolishing my pride; masked and bleeding is not a good look, even (especially?) on Halloween. I bid the month farewell by leaving my house in a torrential rainstorm — having consulted the weather report — wearing socks and shoes with holes in them, and carrying no umbrella. It seems I’ve been distracted. In my…well, not defense, but perhaps something adjacent to it, it was a hell of a month. After a seeming eternity of nothing, everything happened in November. I played three live recitals (three more than I’d played in the previous eight months); finished writing an essay on the anxiety that I’d endeavored to keep hidden for a decade or four; watched, over five agonizing days, as my country finally decided to slow its creep into fascism or oblivion or both. Even for an artist — aka a professional intense person — this was a bit much.

I could have predicted that music would be the thing to sustain me in this strange, often traumatic year: it can be thrilling or consoling, aspirational or confessional, as the situation requires. It has so much to say about loneliness and, in spite or because of that, can make you feel much less lonely. And it is just the thing when you are one Zoom meeting or White House press briefing away from preheating the oven and crawling in. What I did not expect was that Beethoven would be the music that meant most to me in this time. Perhaps this was foolish: Beethoven has, after all, been my greatest obsession for much of my life. But his innate intensity, his permanently gritted teeth, would not seem to provide the needed antidote to all the tooth-gritting we’ve been doing in 2020. (If you’re looking for a Kafkaesque rabbit hole to go down, google ‘Dental issues during COVID’.) But for me at least, he really was the man of the year. Aside from its greatness — which hardly needs to be explained, by me or anyone else — the reason Beethoven’s music has had such special significance for me these past nine months is that it is the product of a person who was profoundly alone, and who found remarkable power and possibility in aloneness. We can never know what music Beethoven might have written in a parallel universe in which he was not unlucky in love, misanthropic and, most crucially, deaf. But I can say with absolute confidence that it would not have been the music he did write. His ability to access his inner life so fully (and what an inner life!), to shrug off the musical language of his contemporaries and replace it with the dizzying and dazzling one he used in his last years, is surely at least in part a result of his extreme isolation. Viewed from the cold light of 2020, that is extraordinarily moving and highly instructive.

When you’re busy living your life, you don’t notice its strangeness, much as you don’t notice the strangeness of the language, culture or religious rituals that you grew up with. So COVID has provided classical musicians with, if nothing else, the chance to contemplate how bizarre aspects of our profession are. How bizarre it is to bow to your audience, when you come from a culture that does not otherwise bow; how bizarre it is to share something as intimate as great music with people you will most likely never speak to or look in the eye. Also: how little our audience looks like our society. (To be clear, I have no need for classical music to have the biggest audience; it’s the unequal access and our tacit acceptance of it that bothers me.) And how much carbon we’re burning by prioritizing globetrotting over the less glamorous but possibly just as meaningful work we might be doing closer to home. I have no answers to these questions, but now that they’ve belatedly occurred to me, I find them impossible to ignore.

[special_offer]

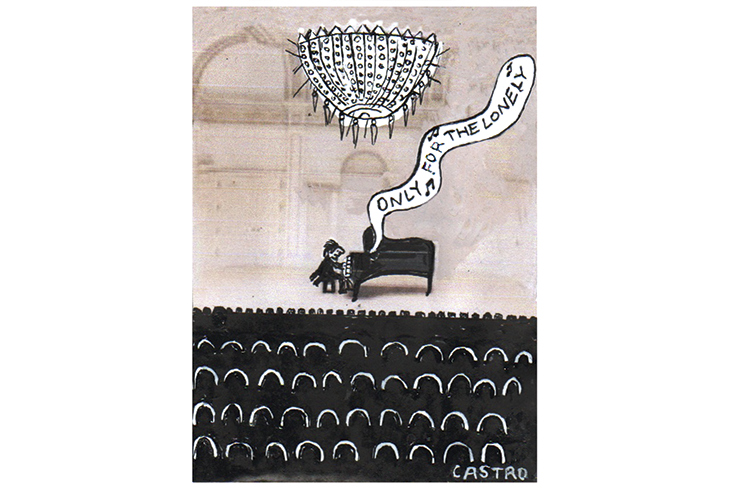

One of my three November recitals took place in an empty hall, its would-be audience yet another casualty of COVID. I’d played plenty of ‘concerts’ this year from my own living room, but they were different: aside from the out-of-tune piano and the tiny room, those home performances always left me the possibility of stopping, screaming an obscenity into the void and starting again. On this occasion, I was in a proper hall, playing a proper piano, playing the program one (hopefully proper) time, straight through, no mulligans. It was in every sense a concert…except in the sense of there being people present to hear it. It was a revelation: there’s nothing like having no one to share the concert with to make you realize that a concert is, at its heart, an act of sharing. When I finished playing Beethoven’s Op. 110, whose finale is an awe-inspiring embrace of life from a man who has been near death, I was a strange mix of euphoric and bereft. The phenomenal generosity of this music rang in the air for a moment, and then the silence crashed in on me. Suddenly I was aware of how badly I’ve missed not just sharing things with people, but generosity itself — being on the giving and receiving ends of it. This is a consequence of COVID, to be sure, but also of the age we live in, where our culture and politics prize selfishness, point-scoring and acquisition, and overlook or even disdain community, empathy for the other and, yes, love. I’ve always rejected the notion that music has morality, and I still do. But at that moment, it was Beethoven who reminded me that the only life worth living is one that enriches and is enriched by others.

Jonathan Biss is an American pianist and writer. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.