Women who can — however tenuously — be described as ‘rebel girls’ are big in publishing now. Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls sold 3.5 million copies in hardback, reflecting a huge cultural push to discover and venerate women in history who kicked over the traces. To publishers, real-life rebel princesses have cool hard-cash value. In this context we come to this book, a scholarly work effortfully seeking out the ‘you-go-girl’ moments of the notoriously woke 13th century.

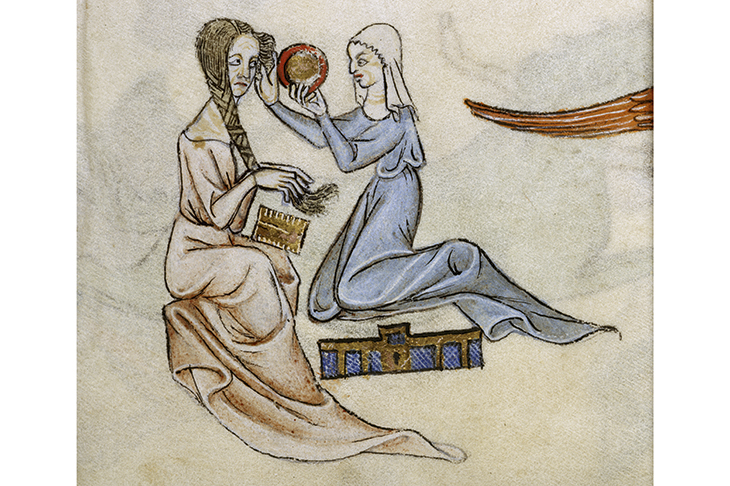

Kelcey Wilson-Lee, who has a doctorate in medieval history from Royal Holloway and works in the development office at Cambridge University overseeing regional philanthropy, has an underlying agenda. But she also has the academic chops to execute it carefully, brushing off apocrypha and relying on contemporary records: wardrobe accounts, psalters, letters and seals. She imagines the experiences of the sisters who are the subject of Daughters of Chivalry with empathy and patience,as they jolt through endless wet horseback journeys while pregnant or recline on cushions in coaches, and ably manages to coax the few sparks of evidence into flames of personality.

To start with the book’s subtitle: yes, the children of Edward I are largely forgotten, but one is reminded of their mother, Eleanor of Castile, every time one takes a train from Charing Cross. (Her son Edward II comes to mind every time one pokes a fire, but that’s for later.) The Victorians rebuilt Eleanor’s monument because as well as having a passion for Gothic revivalism they were moved by the love story of uxorious Edward and his pious Eleanor, who had 16 children and went on two failed Crusades together. With her interest in playing chess and a personal team of scribes, she seems to have managed to construct a family setting in which her daughters had a real — if sometimes Lear-like — relationship with their father. But our age finds dutiful Eleanor deathly dull, so it’s her unpredictable daughters who get the accolade of a book.

Five of them survived to adulthood —not little Berengaria, who sadly never had a chance to show that girls can surf, whatever the patriarchy says — but Eleanora, Joanna, Margaret, Mary and Elizabeth. All experienced dramas straight out of Game of Thrones, that TV parody of high medievalism. Eleanora, the eldest, arriving at a jousting tournament to celebrate her wedding, saw her famed father-in-law, the Duke of Brabant, champion of some 70 jousting matches, wounded so badly he died. Welcome to France, girl!

Wilson-Lee always recognizes as normal the highly circumscribed nature of their lives, while picking out their moments of rebellion with barely contained delight. Mary, who spent her life in the nunnery at Amesbury after being sent there aged six, nevertheless spent huge amounts expressing her personality via the medium of rich clothes, jewels and gambling debts.

But Joanna of Acre is the daughter who stands out. She was called ‘of Acre’ ‘in recognition of her birth at the port city that was the only surviving vestige of a Christian kingdom in the Holy Land’. Until the age of six, Joanna lived with her maternal grandmother at Pontieu in northern France; perhaps the early separation from her parents gave her some of the ‘exceptional independence that she would demonstrate in later life’.

Exceptional independence or sheer bloody mindedness? The new historical ‘rebel-girl’ orthodoxy conflates and celebrates both. As a teenager Joanna fell out with a steward, and

‘sent two knights to Gascony to deliver her version of the story to Edward, along with a letter in which she beseeched: “Dear sire, we beg you… to believe the things which they shall tell you by word of mouth from me.”’

Rather than make up with him, she ran up her own debts, which her parents paid off. Next, she complained that her younger sister Margaret’s household had two more servants than hers — and two weeks later did not attend Margaret’s magnificent wedding at Westminster, even though she was staying in Clerkenwell at the time.

Joanna married the ‘tempestuous earl’ Gilbert de Clare, a Welsh Marcher lord 30 years her senior. Contrary to her parents’ wishes, she went off with him and his retinue of 200 to Glamorgan a week after their marriage, forfeiting her trousseau of seven gowns and a pearl zone, or girdle, which were re-gifted to her sister as punishment. What did Joanna want with seven gowns when she was soon to become truly powerful? When Gilbert de Clare died, ‘in Glamorgan… Joanna could live as a queen in her own right — the ultimate decision-maker, a commanding patron’. Swearing fealty to her father in a solemn ceremony, she convinced him to discharge Gilbert’s debts.

Edward planned to marry her off again, to Amadeus of Savoy. But this was when Joanna jumped in her Thunderbird and drove over the cliff of filial respect Thelma and Louise style. In 1297 she secretly married one of the squires in the retinue of her late husband, an ‘elegantly formed’ young man called Ralph de Monthermer, first arranging for him to be knighted in order to give him a modicum of status. Even more extraordinary than this ‘breathtaking bravado’ was the way she managed over the years that followed to persuade her father first to set the imprisoned Ralph free and then accept him as one of his loyal knights, while she retained the power of the vast estates she inherited from her first husband. ‘It is not considered ignoble or disgraceful for a great and powerful earl to join himself in legal marriage with a poor and lesser woman,’ she wrote. ‘Therefore, in the same manner, it is not reprehensible or too difficult a thing for a countess to promote a gallant youth.’

The final gasp in her life story came when her younger brother, Prince Edward, had so displeased his father with his unmannerly pals, including the young Gascon courtier Piers Gaveston, that the King cut off his son’s income. Ralph de Monthermer sent a letter of protest, as well as his seal and purse, to Edward so that the King could draw on the Clare resources instead. ‘This bold gesture of open defiance could only have come from Joanna,’ writes Wilson-Lee.

Edward I did not always keep his temper with his daughters. When Elizabeth refused to go to Holland to be married off,

‘a note in the King’s wardrobe book records payment “for a great ruby and a great emerald in place of two stones which were lost when the king threw the coronet into the fire”.’

Wilson-Lee reads into this that the king clearly regretted his anger, both replacing the stones and allowing the princess to remain a while longer in England. ‘Elizabeth, therefore, had managed to buy herself some more time as an independent princess.’

Whoop, whoop! If anyone can find me another clutch of rebel princesses, let’s get crowdfunding and live-stream a vlog about them. This stuff is too good to leave to historians.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.