Absent mothers resonate in the latest offerings from two heavyweights of French literature. Getting Lost is the diary kept by the prize-winning novelist Annie Ernaux while she was having an affair with a married man in 1989. Ernaux has already written a novel about this relationship. Now we have a more immediate and intimate account. Meanwhile, the octogenarian feminist and literary theorist Hélène Cixous continues her own brand of écriture féminine in Well-Kept Ruins. For the uninitiated, Cixous’s stream of consciousness is like reading Molly Bloom with a PhD from the Sorbonne, a raft of awards and a keen eye for cognitive dissonance.

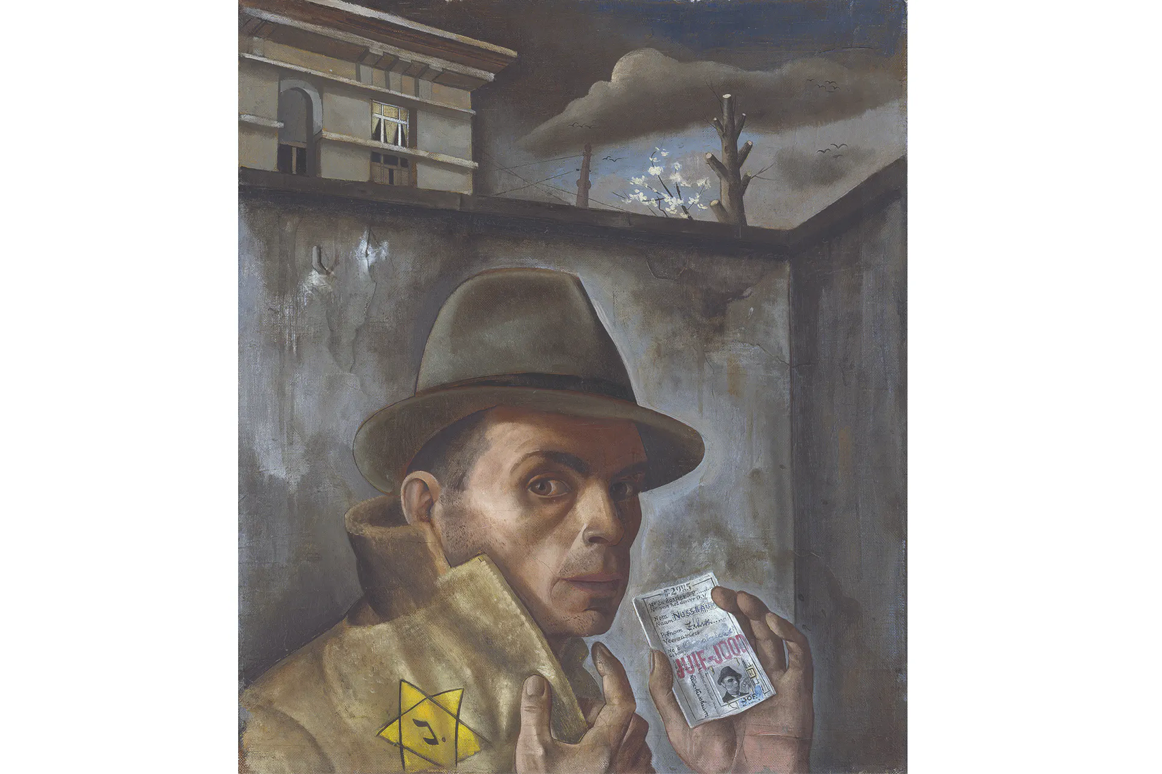

Cixous’s new book hinges on her arrival in Osnabrück, Germany, to receive the Justus Möser Medal, awarded by the city council to writers who commemorate the place. (Erich Maria Remarque was a previous recipient.) The author has written about Osnabrück before, as the birthplace of her mother Ève, an Ashkenazi Jew, born in 1910. In the 1930s, Ève fled Hitler’s Germany to find refuge in Algeria, where she met Cixous’s father, a Sephardic Jew, and a practicing doctor — until the Vichy regime removed French citizenship from Jews. Hélène was born in 1937. Her father died in 1948, and in 1971 she and her mother were exiled from Algeria.

It was an expulsion that marked Cixous deeply. As the Bürgermeister bestows the city’s highest honor on her (in a ceremony that Remarque found “boring”), Cixous finds herself contemplating stories of Osnabrück’s sixteenth-century witch trials — and how the trauma those women endured was echoed in her own mother’s persecution as a midwife and a suspicious (Jewish) woman.

In a Protestant city, Cixous circles the ruins of its demolished synagogue. She imagines the stones, and the women’s bodies, hunched into balls, as they endured trial by water. She invites us to consider the culpability of witnessing, and then closing our eyes to, the horrors around us. She moves from the trauma of an exiled child to the atrocities of witch-burning to the plight of pieds noirs and Jews in the space of a single paragraph. The prose is fluid. Punctuation evaporates. Focus scatters. This is a writer who cannot sit in a café without composing a riff on national identity:

Your all-in-one-café-bar-bistro rant morning noon afternoon evening all times for all ages all generations, dogs included, high-concept, high point of German gastronomy since and for ever.

Well-Kept Ruins is shaped by a yearning to recover the irrecuperable. Cixous is compelled to revisit the fates of these castaways. She is a daughter who attempts to commemorate a midwife; a writer who finds herself through the bond of mother and child.

Annie Ernaux’s reputation is similarly illustrious. But her suffering is different: it is awaiting the attentions of a married man — and being abandoned by him. In Getting Lost, she is nearing fifty, divorced and living in the suburbs of Paris with two adult sons. The married man is younger than her and, most enticing of all, Soviet: being unable to situate him socially and intellectually is part of his attraction. Also, he knows Proust’s law of desire instinctively: “Never say anything, never show too much love.”

Ernaux explores obsession in a way that transcends the usual lament of a cast-off mistress. Instead, she contemplates a fevered mind, unbound by social expectations. A woman possessed trudges, distractedly, through commitments — sons, work, friends — as boxes to be ticked, while she waits for desire to be lit. She equates the pain of her lover’s final departure with her mother’s death; and the loss of the parent who “spent all day selling milk and potatoes so that I could sit in a lecture and learn about Plato” feeds her writing. If assignations are “a terrible descent into death,” writing is the opposite: “the absence of time.”

Perhaps this explains the compulsion to rework the same material. Cixous’s book is a genealogy of exile; Ernaux’s is suspended animation. Both writers have been served well by their translators (in Cixous’s case in her diffuseness and the rhythms of her wordplay; in Ernaux’s in her terseness) and both proclaim their difference to mainstream society. Each triumphs in finding the potential of her vulnerability.

“We’re undone by each other,” Cixous argues. “And if we’re not, we’re missing something.” Vulnerability, in this formulation, is perhaps a last chance of true redemption.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.