A few years ago, the private school where I teach asked me to offer an evening class on James Joyce’s Ulysses to adults. The idea was to remind alumni, parents and other community members what it feels like to be in one of our enriching classrooms. For over a decade, my Ulysses senior elective had been a major feature of our course catalogue; now, a few adults were about to pop the hood on this infamous tank of a book.

As course registrations began to trickle in, I recognized the surnames of current and former students. Then an administrator joined the course, and I had a flutter of nerves at the realization that one of my bosses was actually going to read Ulysses and encounter the disreputable content that lurks within. My cover was blown. Toward the end of the course, she lingered behind after class. With her head cocked, she said, “All these years, you’ve been reading this book with our students? Right under my nose?”

Many passages from Ulysses, if appearing almost anywhere else, would probably get me fired. A century ago, however, this great novel was just as susceptible to censorship as any other work of art. The book was banned for over a decade after the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice won an obscenity case in the Superior Court of New York in February 1921. This case focused on the “Nausicaa” episode, in which Mr. Leopold Bloom, the novel’s thirty-eight-year-old protagonist, ogles a young woman sitting a few yards away from him on the beach, his hand busy in his pocket. The woman, Gerty MacDowell, receives Bloom’s attention with pleasure and leans back to expose her tights as fireworks light up the twilight sky:

And she saw a long Roman candle going up over the trees, up, up, and, in the tense hush, they were all breathless with excitement as it went higher and higher… She would fain have cried to him chokingly, held out her snowy slender arms to him to come, to feel his lips laid on her white brow, the cry of a young girl’s love, a little strangled cry, wrung from her, that cry that has rung through the ages. And then a rocket sprang and bang shot blind blank and O! then the Roman candle burst and it was like a sigh of O! and everyone cried O! O! in raptures and it gushed out of it a stream of rain gold hair threads and they shed and ah!

The court found the novel obscene and made it a crime to publish, sell, purchase, or import Ulysses in the United States; the censors in the UK followed the Americans’ lead. Today, governments seem less interested in policing the arts, but it’s worth considering how a publishing house in the era of trigger warnings and self-censorship might weigh the novel’s obscenity and other “problematic” content against its literary merits.

When I teach Ulysses, the first moment that provokes objections and discomfort appears in “Calypso,” the chapter in which Mr. Bloom is introduced. On his morning visit to the butcher shop, Mr. Bloom finds himself waiting in line behind a pretty young woman, his neighbor’s housemaid: “His eyes rested on her vigorous hips. Strong pair of arms. Whacking a carpet on the clothesline. She does whack it, by George. The way her crooked skirt swings at each whack.” When the woman leaves the shop, Mr. Bloom hopes “to catch up and walk behind her if she went slowly, behind her moving hams. Pleasant to see first thing in the morning. Hurry up, damn it.”

Joyce lets us in on the character’s unmediated private thoughts, and his gawking here usually prompts a complaint. How come Joyce sets Bloom out to be this kind and thoughtful guy, only to then show us he’s actually a creepy lech and an objectifier of women? But then, another student might reframe the scene in the context of its artistic intentions. If Joyce is seeking to replicate the involuntary patterns and attentions of a real person’s private thoughts, then, let’s be honest, most of us will notice an attractive person in the checkout line. Another student might even admit that they found Mr. Bloom’s exposed quirks and guilty pleasures funny.

As is often the case, Ulysses provides us with the language we need to process its content. The “Circe” episode, written as a surreal theatrical script, anticipates the drama of #MeToo as it depicts Mr. Bloom’s fantasy of being tried in court and shamed for his surreptitious thoughts and inappropriate advances:

THE HONORABLE MRS MERVYN TALBOYS: He observed me from behind a hackney car and sent me in double envelopes an obscene photograph. He urged me to misbehave, to sin with officers of the garrison. He implored me to soil his letter in an unspeakable manner, to chastise him as he richly deserves, to bestride and ride him, to give him a most vicious horsewhipping.

MRS BELLINGHAM: Me too.

MRS YELVERTON BARRY: Me too.

(Several highly respectable Dublin ladies hold up improper letters received from Bloom.)

Mr. Bloom is no angel. Later in the hallucinatory episode, Mr. Bloom has an encounter with Bella Cohen, the madam of a brothel. In one sequence, the characters switch genders (Bella becomes Bello, and Bloom becomes a woman) and Bloom reveals the depths of his subconscious masochism:

(Bello bares his arm and plunges it elbowdeep in Bloom’s vulva.) There’s fine depth for you! What, boys? That give you a hardon? (He shoves his arm in a bidder’s face.) Here, wet the deck and wipe it round!

Even the most desensitized, internet-addled contemporary reader should be appalled to encounter this imagery in print. Similarly triple-X-rated passages are scattered throughout the book. How might an acquisitions editor at a publishing house receive them today?

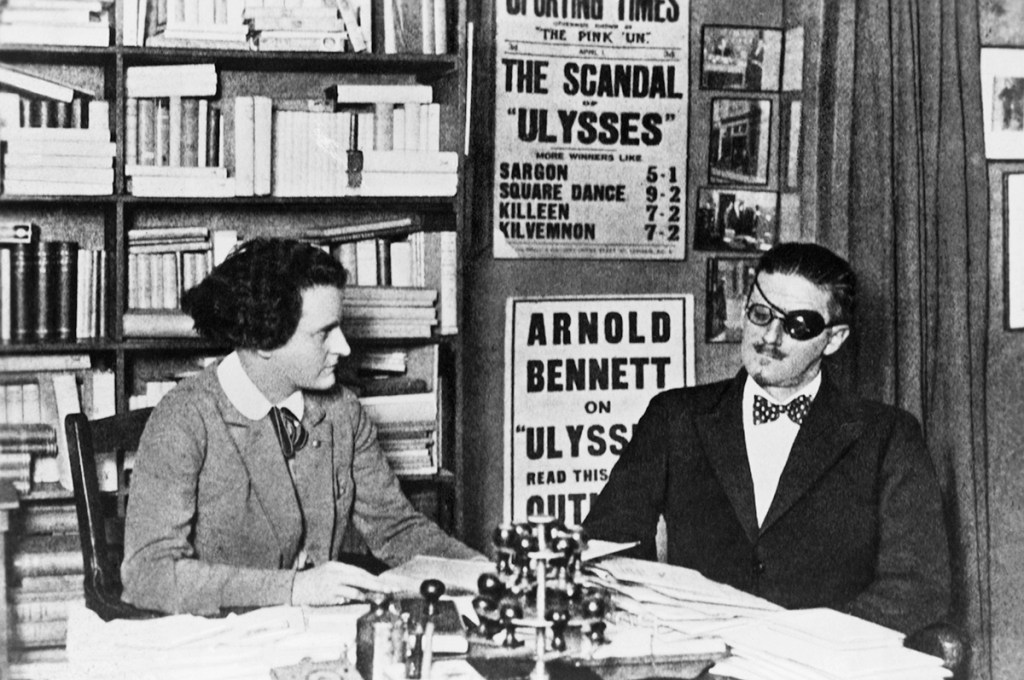

After Ulysses was blocked from the English-speaking world, Sylvia Beach, the proprietor of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris, heroically agreed to publish the book using French printers. It was finally released on Joyce’s fortieth birthday: February 2, 1922. The Anglophone banning of Ulysses, like some contemporary cancellations, turned out to be a PR gift. Beach immediately emphasized the novel’s edgy allure. In the initial prospectus to potential subscribers, there were boasts in large font of the novel being “suppressed four times during serial publication.”

When a hostile review of Ulysses appeared in the Sporting Times — of all places — Beach prominently displayed its headline, proclaiming “The Scandal of Ulysses,” in her bookshop. Beach and Joyce dismissed the censors as puritanical and jejune, appealing instead to the emerging progressivism that would scoff at small-minded objections against high art. Like the millennial generation’s “OK Boomer” meme, modernism rolled its eyes at the prudishness of the tottering Victorians. This strategy gave readers permission to ignore outdated moral standards, creating an aura of rebellious elitism that continues to surround Ulysses a century later. The book remains a hipster classic partly because of the way that Beach and Joyce packaged the novel’s obscenity as an integral element of its renegade erudition.

Its prestige further benefited from the book’s initial scarcity in the marketplace. Beach and Joyce stoked demand by limiting the supply to 1,000 copies available only by subscription. The first edition of Ulysses thus immediately became an object of both cultural and speculative value. Ezra Pound advised his parents in May 1921 that “I know of no sounder investment (even commercially) than the first edition of Ulysses.” Indeed, within eight months of publication, copies were sold on the secondary book market for over 350 percent of the initial sales price.

As any reader who has pulled out a copy in a coffee shop or train station knows, the novel still carries a powerful aura, communicating something clear: this reader is a nerd gone rogue. Yet because it is notoriously difficult to read, lots of people know Ulysses by its scholarly reputation but have only a vague understanding of its plot, its groundbreaking style or its obscenity. I fear that those scandalous passages cited above will have an outsize influence on those people’s idea of the book. I worry also that similar passages taken out of context might now cause a publishing house to say “Why bother?” and leave a work of art like Ulysses out of view.

The truth is this novel is wholly expressive of the human experience. It is so ingeniously constructed that its literary value vastly outweighs its unpalatable moments. Anyhow, the book’s obscenity has been shruggingly accepted as fact for over a century.

In the end, teaching Ulysses hasn’t gotten me fired in part because of the initial marketing of the book, but more so because this novel presents a timeless celebration of the human spirit — good, bad and most certainly ugly.

Patrick Hastings’s The Guide to James Joyce’s Ulysses is published by John Hopkins University Press ($22). This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.