Lydia and Luca are hiding in the shower room of their home while 16 members of her family are murdered. Lydia’s husband, a journalist, wrote about the latest drugs cartel in Acapulco and now, to stay alive, the mother and small son must disappear to America. Instead of the middle-class life Lydia has enjoyed as a bookshop owner, she and Luca must become one of those nameless, desperate migrants against whom President Trump vows to build his wall.

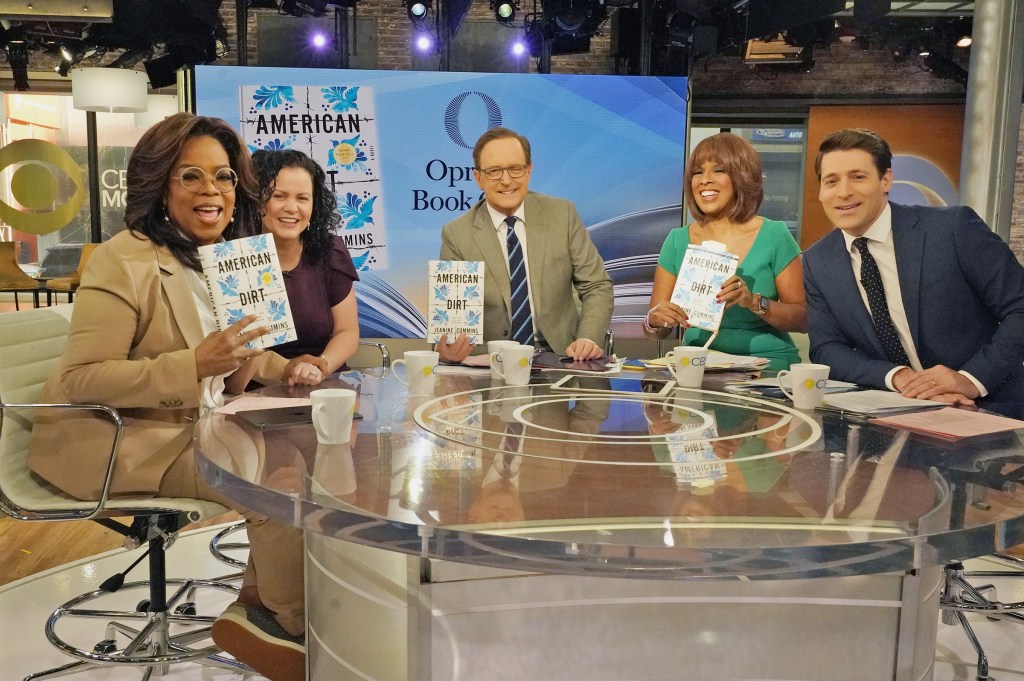

So begins Jeanine Cummins’s third novel, and if you think this is another Roma-style examination of the lives of poor Mexicans, think again. Cummins, who is not Mexican, says in her Afterword that she wishes this story had been written by someone who is (and indeed, the great thriller writer Don Winslow has already explored the cartels in his novels). There have been vociferous complaints of cultural appropriation and gross misrepresentation of its subjects in, most notably, the New York Times. Cummins certainly tries hard to spread her sympathies. In American Dirt even the most brutal criminals are educated and civilized: Javier, the head of the cartel, is a serious reader, the only other person who values the ‘secret treasures’ in Lydia’s bookshop, and she believed they were soulmates.

Now, because of the newspaper article, Javier has put a price on their heads. Yet if Lydia and Luca are to escape in an age of mobile phones, she must use every ounce of her cunning and instinct. Despite a university degree and her life savings, she has ‘no access to the kind of information that has real currency on this journey’: how to jump onto the roof of La Bestia, the lethal freight trains traveling north, how to find a trustworthy coyote to smuggle them into America, how to avoid notice and keep on running. If you think of The Grapes of Wrath being given the momentum of The Thirty-Nine Steps, you might get an inkling of the wild ride to come.

Some of the action is seen through Lydia’s eyes, and some through that of Luca, one of those hyper-intelligent and improbably obedient child protagonists who are over-familiar from novels like Room. Other migrants met on this odyssey of desperation and terror have their own tales, like the dangerously beautiful Honduran girls Soledad and Rebeca who befriend them. Almost everyone they encounter has a conscience. The priests and nuns who help the migrants with food and rest are (for once) genuine Christians. Even her gangsters have some humanity, which makes their acts more monstrous. ‘It seems impossible that good people… can exist in the same world where men shoot up whole families at birthday parties then stand over their corpses and eat their chicken,’ Luca thinks. As a portrait of the deepening societal breakdown in Mexico, this gives a human face to ‘a pageant of blood and grisly one-upmanship’, and an acute contemporary crisis. ‘Good people do not run away,’ the corrupt commander of a law enforcement agency tells Luca. Yet these people are good — and their courage and cleverness are exactly what any enterprising country should treasure, not reject.

It might be argued that this novel, saturated with compassion for migrants of all kinds, comes perilously close to sentimentality. Jeanine Cummins excels, however, at balancing extreme narrative tension with judgment, layering in vivid psychological detail and moral choices as her protagonists move through a landscape of agriculture, cities and desert. How Lydia and Luca cope with grief, guilt, shock, boredom and fear are all conveyed in clear, crisp prose, as is their intense physical suffering from heat, cold, water, dryness, hunger and thirst. What Americans call dirt has a double meaning as they struggle towards the land of the north. Their story is above all one of love, and hope.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.