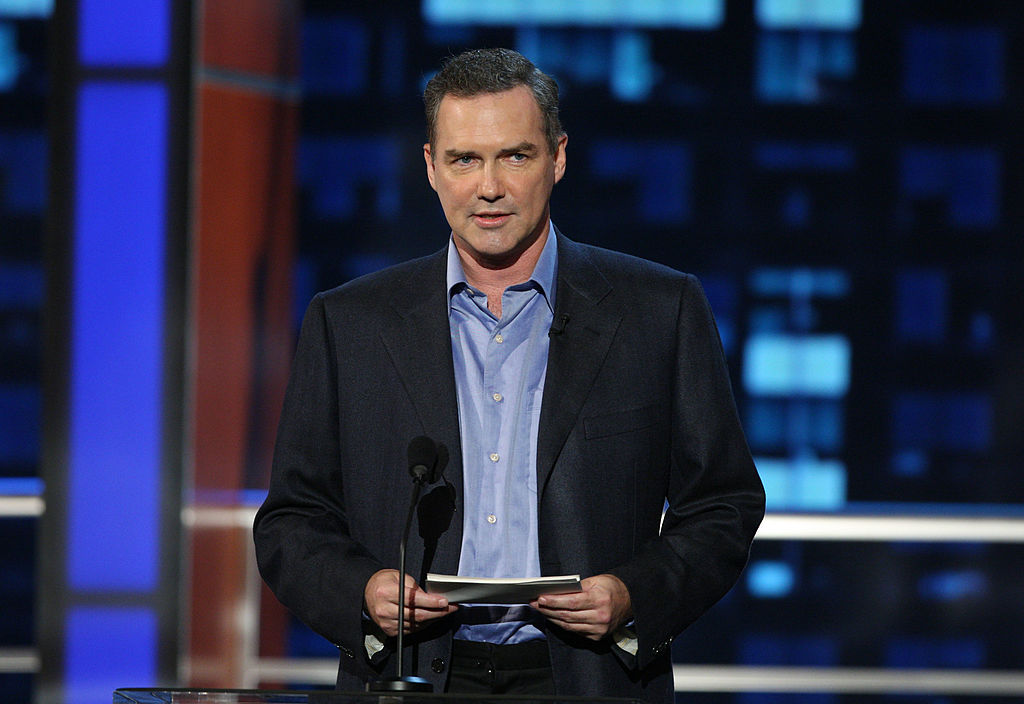

Norm Macdonald claimed to have coined the phrase ‘fake news’ two decades before Donald Trump brought it into the political lexicon. That’s just one of dozens of examples of how the late Canadian-born comic left a mark on American culture.

As host of Saturday Night Live’s long-running ‘Weekend Update’ segment during the mid-1990s, Macdonald often used the term when welcoming audiences. ‘I’m Norm Macdonald,’ he would begin, ‘and now, the fake news.’ What followed, however, almost always jumped the rails of what could reasonably be described as news satire. For a few minutes every Saturday night, Macdonald would throw curveballs at viewers, alternating between the types of one-liners your grandfather might enjoy and eviscerations of embattled celebrities like Michael Jackson and O.J. Simpson. (Shortly after Simpson’s acquittal, the comedian famously joked on air, ‘Well, it’s finally official: murder is legal in the state of California.’)

To me, however, the most unusual and endearing part of Macdonald’s routine was the way he responded to the jokes that fell flat. The vast majority of these duds were, of course, intentional. Throughout his years on SNL, he became known for peppering in non sequitur punchlines, often at the expense of Frank Stallone, the less celebrated brother of the Rocky star. In such moments, the uninitiated could only glance at each other sheepishly, wondering whether they had missed the joke or whether it was even a joke at all.

Rather than look away or try to salvage the bit, Macdonald would stare silently into the camera, a thin smile etched across his face, dragging his audience deeper into the awkwardness. To his admirers, Macdonald’s ability to subvert expectations provided SNL with a sense of true danger — a quality that had otherwise been jettisoned by one of television’s culturally safest shows.

When news broke yesterday that Macdonald had passed away at the age of 61 after a long, private battle with cancer, countless industry peers took to social media to extol his originality, delivery, and razor-sharp wit. And while Macdonald had clearly mastered the technical aspects of his craft, as a fan, I was most captivated by the degree of fearlessness his comedy must have required. During his late-night appearances in particular, he exuded a genuine coolness — suggesting he didn’t particularly care whether the audience laughed with him, at him, or not at all. Never was this quality on greater display than during his now infamous appearance on The Tonight Show with Conan O’Brien, when he confounded and regaled host and viewers alike with a four-minute-long shaggy dog story about a moth visiting a podiatrist (yes, it got laughs).

While Macdonald was beloved for his absurdist anecdotes, friends and devoted fans also recognized him as a great intellect, with a well-known appreciation of Tolstoy and a philosopher’s curiosity about life, religion, and the world around him. Despite keeping much of his life, and later his illness, private, he showed no reservations about occasionally startling interviewers with his blunt belief in the existence of God. Indeed, Macdonald’s ability to riff on religion in a way that was both funny and approving seemed downright countercultural by the comedic standards of today.

He also frequently showed contempt for fashionable atheists who seemed to take pleasure in talking down to the poor rubes who dared place their hopes in a higher power. ‘Hey, you’re not going to believe this,’ Macdonald once wrote, ‘but Bill Maher is giving away the solution to all our problems — for free!’

Musings about illness and death were also frequent themes in Macdonald’s comedy. Watching him perform at Washington’s Lincoln Theatre a few years ago, I marveled at his ability to summon guilty chuckles from his audience over stories of airplane crashes and devastating medical prognoses.

The afterlife was another subject of intrigue for Macdonald, whose act sometimes featured a bit where he’d debate whether to embrace the believer’s idea of heaven or the atheist’s assertion of eternal nothingness. Asking for the believer’s pitch first, he’s promised that when he dies he will ‘go up and play a harp on a cloud.’ Turning to the atheist, he asks, ‘What do you got? What happens when I die under your plan?’ ‘Well,’ the man replies, ‘we put dirt on you.’ Macdonald decides that since the correct answer is ultimately unknowable to him in life, he would be happier accepting an afterlife of clouds and harps.

As a fan and admirer, I like to believe that Norm made the correct choice. Now, having reached the end of his own joyful, strange, and hilarious story, I hope he’s found a punchline far grander and more unexpected than even he could have imagined.