Alexander the Great famously wept when he saw the breadth of his domains, for there were no more worlds left to conquer. Had he been alive today, he would simply have signed a Netflix deal and reaped hitherto unimaginable rewards.

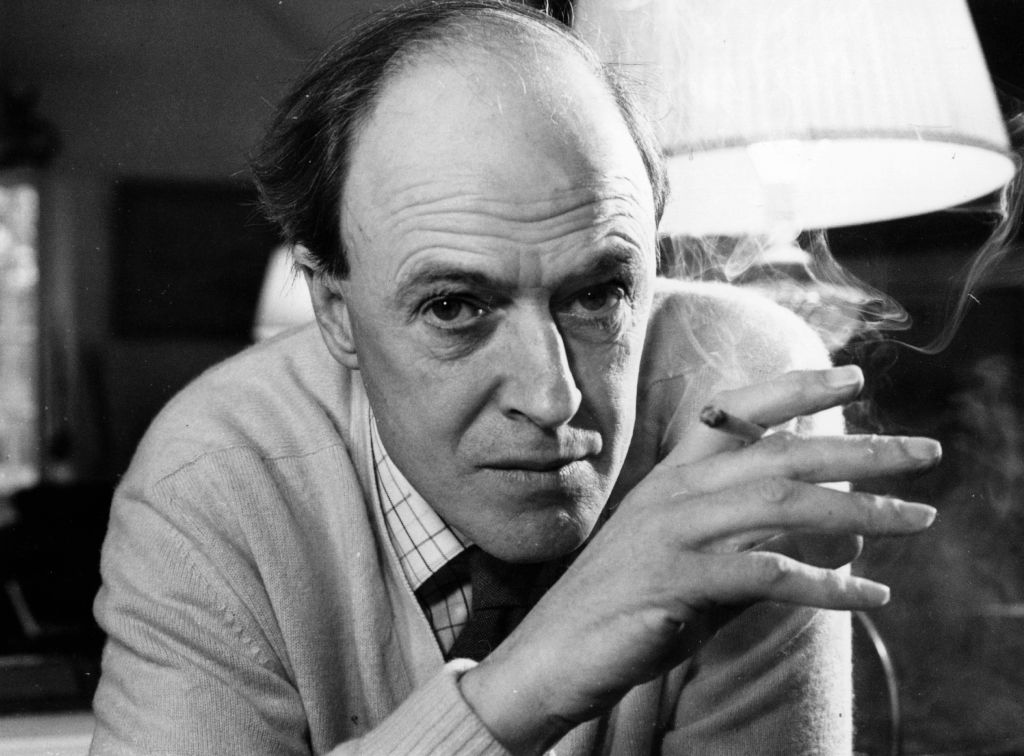

Netflix’s announcement that they have paid an undisclosed but presumably staggering amount of money for the complete works of Roald Dahl, to add to the licensing agreement that they already had with the Roald Dahl Story Company, seems set to flood the streaming service with unlimited Dahl adaptations over the coming years. Already, we are promised a new film of the musical of Matilda and a television series based on Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, but these are merely the tip of a very large, very lucrative and wholly fantastical iceberg.

Netflix seem to be delighted with their new acquisition. Ted Sarandos announced little less than world domination when he said that the purchase ‘opened our eyes to a much more ambitious venture — the creation of a unique universe across animated and live action films and TV, publishing, games, immersive experiences, live theater, consumer products and more’. In other words, Dahl — whose estate continues to produce millions of dollars every year — continues to be big business three decades after his death, something that his grandson Luke Kelly and Sarandos said would lead to ‘maintaining their unique spirit and their universal themes of surprise and kindness, while also sprinkling some fresh magic into the mix’.

It was clearly a different Roald Dahl whose macabre and twisted stories that I read, and loved, while I was growing up. His major appeal was not the ‘universal themes of surprise and kindness’, but the off-kilter and often sadistic imagination exhibited within his novels and short stories for children and adults alike. Few can forget the fates that such characters as the grotesque Miss Trunchbull in Matilda and the ungrateful and spoilt child protagonists in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory meet, or the disturbing resolution of The Witches, in which the narrator contemplates his imminent demise in his new guise as a mouse. And this is before we get onto his brilliant, twisted short stories, which show up their spiritual successor Black Mirror — another Netflix show — for the unadventurous dross it is. Hopefully it will not simply be Dahl’s children’s books that get the streaming treatment. With a budget of $1 billion devoted to the estate, there’s more than enough to go round.

Yet Dahl himself is a Problematic Figure whose unambiguously anti-Semitic statements (‘There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity, maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews…even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason’) led to a groveling apology by his estate last year, in which they regretted ‘the lasting and understandable hurt caused by some of Roald Dahl’s statements’ and stated that ‘Those prejudiced remarks are incomprehensible to us and stand in marked contrast to the man we knew and to the values at the heart of Roald Dahl’s stories, which have positively impacted young people for generations’.

There is nothing to be gained by the retroactive cancellation of Roald Dahl. The books are loved by millions, and the egregious anti-Semitism and bigotry of its author died with him. Yet there is a certain irony in Netflix, that most woke of corporations, eagerly seeking to embrace the legacy of a man who reveled in upsetting and confounding the dull, repressive corporate world.

Dahl lionized the individual and the eccentric over the tiresome forces of adulthood, and treated the world of big business as a regrettable blight on imagination and play. Netflix might style themselves as imaginative Willy Wonkas, transporting wide-eyed Charlie Buckets into unlimited worlds of fun and excitement, but the cynical might regard them as more akin to the obnoxious Mike Teavee, the boy fixated on television to the exclusion of all else. Mike ends Charlie and the Chocolate Factory chastened and stretched to an enormous size after his wrongdoings. We can only wonder if Sarandos, Kelly and the rest will meet with similar humiliation one day.