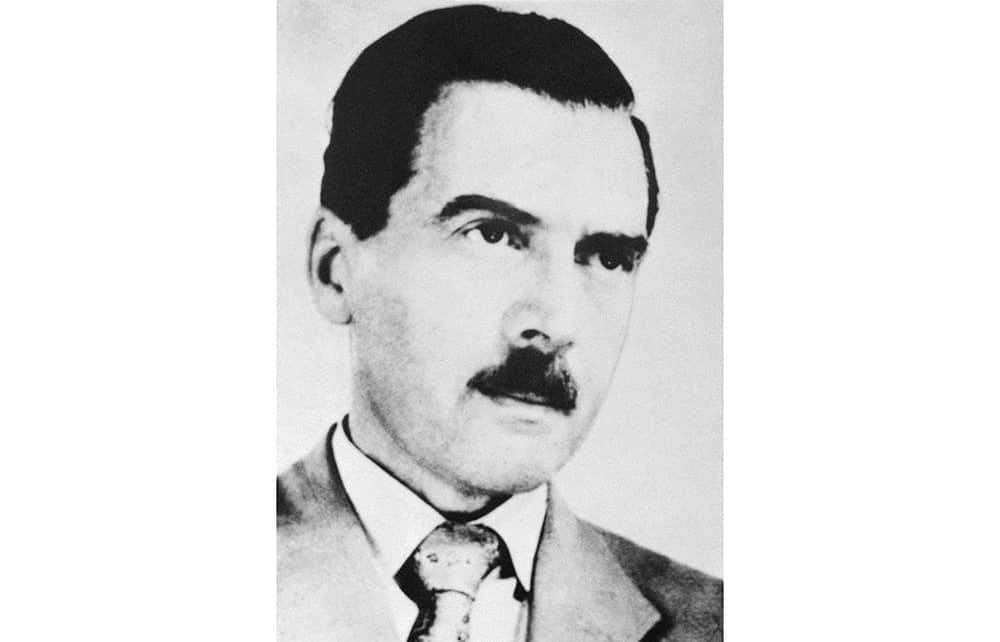

Who would have thought that someone would write a novel about Josef Mengele, the Auschwitz doctor and infamous experimenter on live human bodies? Other characters in the French writer Olivier Guez’s story are also from the Nazi gang of debased criminals: Adolf Eichmann, Franz Stangl, the concentration camp commandant, and Klaus Barbie, the Butcher of Lyons.

This is a historical novel, and Guez has researched it well. He invests the structure of events with his imagination and has Mengele relate his experiences throughout his long avoidance of capture. There’s a vivid sense of reality about the crazed, unrepentant eugenist’s attempt at an acceptable fugitive way of life, and Guez holds our attention by building dramatic suspense. He is expert in the use of both imagined dialogue and reflective internal debate.

Mengele graduated to become a SS doctor at Auschwitz where he was often responsible for the Judenrampe selection of Jews, gypsies and social misfits either for the gas chambers or his laboratory experiments of “injecting, measuring, bleeding, cutting, killing and performing autopsies.” He kept a “zoo of children,” was particularly concerned with twins and had a collection of blue eyes pinned to his office walls.

Post-war, he evaded capture by assuming false identities and hiding in the Bavarian countryside. Then, in 1949, using an escape network organized by unreformed Nazis, he traveled to South America, where he was supported by funds, funneled through Nazi conduits, from his family’s agricultural machinery company in Germany.

Juan Perón wanted Argentina to be the National Socialist Christian state of the Americas opposing the US, and he profited from the advice of German military experts. Paraguay, Uruguay and Brazil all favored Nazi Germany. During the war, British security co-operation at the Rockefeller Center in NYC, staffed by Oxford dons — the philosopher A.J. Ayer, the classicist Kenneth Maidment and the historian Bill Deakin — were detailed to monitor events in South America, where many Nazi war criminals would later seek haven. Mengele was everywhere assisted by prominent Nazis. Dieter Menge entertained him in his estanzia near Buenos Aires: “A bust of Hitler brightens up the garden and a swastika in granite adorns the bottom of the swimming pool.” Wolfgang Gerhard, a São Paulo Nazi fixer, had “a Christmas tree topped by a swastika.”

And so Mengele, the “Prince of European Darkness,” disappeared from mainstream European view. He was hunted, harried and haunted by Mossad and eventually by West Germany, but after the Six-Day War and Eichmann’s kidnapping, Israel had more pressing priorities in the Middle East.

Guez’s uncovering of Mengele’s life in South America makes compelling reading. He dramatically represents the curious details of the psychopath’s harrowing, mentally destructive survival amid the various strata of Argentinian and Brazilian society as infinitely more than he deserved. This surprising historical novel, highly successful in its shocking impact, should be read as a timely warning of atrocities that barbaric, deranged fanatics commit in war.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.