We can probably blame George and Ira Gershwin. It was that brilliant duo who, in 1937, penned the memorable lyric ‘They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round.’ The song has been recorded by at least 15 artists over the years, from Fred Astaire to Lady Gaga, and is embedded in the consciousness of the West.

But its headline message — medieval people are stupid — is total nonsense. No one, as Professor Seb Falk points out in this brilliant study of medieval astronomy and learning, ever disbelieved the world was round, and medieval people were far cleverer than they get credit for. Half the population, for one thing, he says, was literate.

The idea that the Middle Ages was a time of superstition, brutality, short lives, nonstop dysentery and a retreat from rationality has many promoters. This slander is repeated in Pulp Fiction, when Marsellus says to his hillbilly attackers: ‘I’m gonna get medieval on yo’ ass.’ The myth has its roots in the Reformation, when Puritan reformers sought to discredit the 900 years that preceded them as a fog of ignorance. We see the same notion in the 18th century, in Pope’s celebrated couplet about Isaac Newton: ‘Nature and nature’s laws lay hid in night./ God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.’

In actual fact, as Falk points out over a riveting though occasionally knotty 400 pages, the so-called Dark Ages were characterized by intense scholarly inquiry into nature and nature’s laws. Like the ancient philosophers before them, the medievals — generally the monks, who had the time for this stuff — studied the motions of the planets and stars and moon and sun, produced highly complex tables and wrote voluminous treatises.

They also developed, and possibly perfected, the ancient calculating instrument, the astrolabe. Made famous by Chaucer’s work, A Treatise on the Astrolabe, astrolabes were the iPads of their day, beautiful portable devices made for measuring the heavens and taking coordinates. Fitted with a viewing tube, the astrolabe was a sort of map of the cosmos combined with an annual calendar with which you could not only tell the time but also find the position of the sun. It was this viewing tube that led to a gag in Chaucer’s ‘Shipman’s Tale’, where a lusty, astrolabe-owning monk attempts a seduction: ‘Let us dine as soon as that ye may, for by my cylinder ’tis prime of day.’

The scientists of the Middle Ages, says Falk, also invented the mechanical clock. They toiled away at the idea and in 1273 seemed to have cracked it: a mechanical clock was installed at the Norwich Cathedral priory, and soon after clocks appeared in London, Westminster and Oxford. Falk reserves particular praise for a terrifically complex astronomical clock at St Albans Abbey.

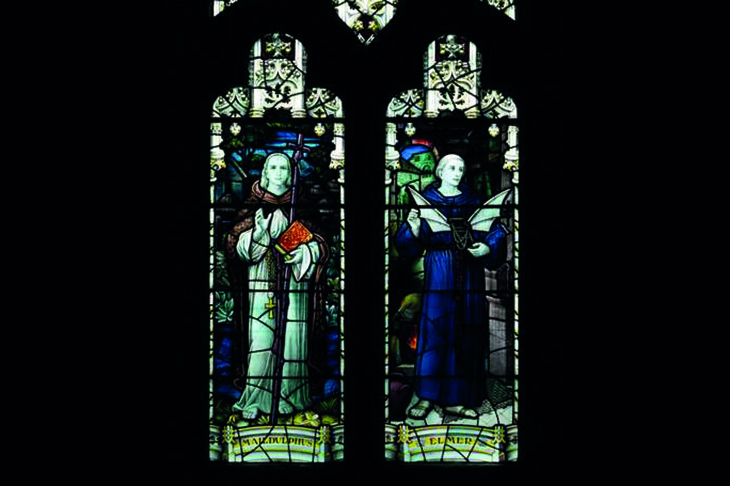

In support of his thesis, Falk tells the story of a monk named Eilmer at Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire who invented the glider around 1100:

‘He fastened wings to his hands and feet and leapt from a tall tower. According to the abbey chronicle, he flew more than 100 meters, before a gust of wind caused him to fall and break his legs… Eilmer piloted an experimental glider, not wholly without success, almost 500 years before Leonardo da Vinci sketched a similar flying machine.’

Far from being isolated in ignorant bubbles, medieval scholars from all over the known world worked with each other. The Light Ages shows how Islamic, Jewish and Christian scholars were constantly borrowing ideas from one another. One well known example is the monks’ reading of Islamic translations of Aristotle. Christians loved the ancient Greek philosopher.

True, they believed in God, and science and religion were intertwined. But does that make them superstitious and ignorant? As well as the clock and the astrolabe, the medievals invented the university, where the ancient curricula of the Trivium and the Quadrivium were pursued. It was a progressive time in other ways. We might also mention the guilds, hospitals, cathedrals, light-filled art (as David Hockney has shown in his book Secret Knowledge), a short working week and a ban on usury. I agree with Falk. Dear, naive Steven Pinker, apostle of progress and disrespecter of the past, is wrong. We need to give more respect to the giants of the Middle Ages on whose shoulders we stand.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2020 US edition.