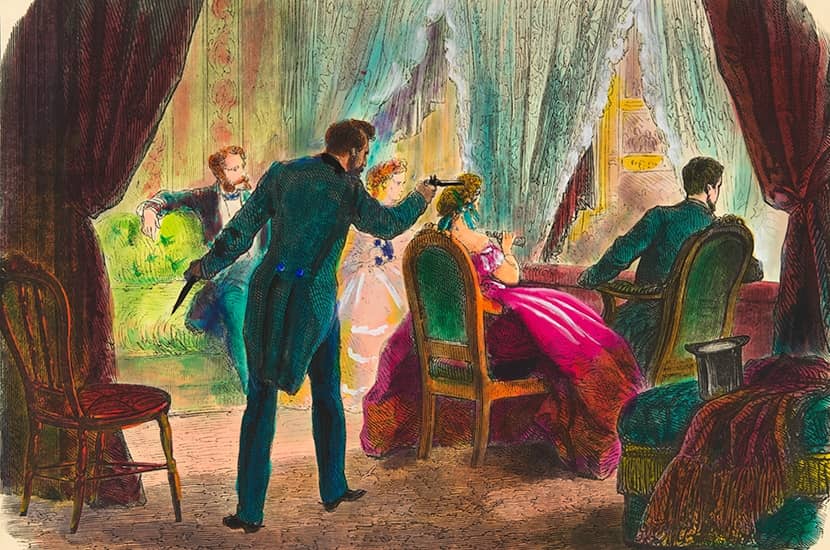

Were it not for an event on the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth would be remembered, if at all, as an actor; brother of the more famous Edwin, and son of Junius Brutus — a footnote to the history of American theater. But that night Booth leaped on to the stage of Ford’s theater, Washington DC, shouting “Sic semper tyrannis!” before fleeing. He had just shot Abraham Lincoln.

Five days earlier the Civil War had officially ended. Booth, a Confederate sympathizer, feared Lincoln would overthrow the constitution — he was already promising votes to freed slaves. The assassination was Booth’s way to “avenge the South.”

Karen Joy Fowler’s novel is not an examination of the life and mind of the killer but a labyrinthine and detailed exploration of the family that produced him. Fowler has form in family dynamics: her joyous, heart-breaking novel We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves anatomized the complexities of parental and sibling bonds under extraordinary stress. She does something similar in Booth, charting the personal stories that culminated on that fateful day in Washington.

When the Booths moved into a remote cabin in the Baltimore countryside in 1822 there were good reasons for secrecy: the couple were fleeing scandal in London. Junius, the celebrated Shakespearean actor, continued to dazzle audiences and critics on both sides of the Atlantic, while offstage navigating the wreckage of his personal life. Meanwhile, Mary bore him ten children, six of whom survived.

Dangerously free-thinking and anti-slavery, Junius is the novel’s most vivid character, bullying the offspring he claims to adore — Rosalie, the clever daughter deprived of an education; Edwin, reliable and unappreciated; Asia, family beauty and determined biographer; and John, who watches enraged and embittered as Edwin takes on his father’s mantle to become America’s foremost actor.

Constantly fighting the catastrophic debts run up by their alcoholic father, the siblings are both rivals and loyal protectors in each other’s lives and loves, as Fowler draws us into their secret dreams and ambitions, through decades of upheaval in a dangerously divided nation.

Like a heartbeat between the family chapters we get brief, telling glimpses of Lincoln; his words, his life, as he moves towards his tragic destiny. A great man felled by an upstart footnote. Booth would achieve the lasting fame he craved, not for his Hamlet or Richard III, but as the man who assassinated the president of the United States.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.