We are here, to feast on the fabulous, lavish, ludicrous, deluxe and delightful 50th anniversary reissue of the Kinks undisputed 1968 masterpiece, The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society.

In the United Kingdom, home to a royal family appointed by God who live in various castles; five-day cricket matches, football hooligans, innate conservatism, quiet revolution, natural surrealism, and cider that tastes of dead rats; drunkenness, habitual racism, suspicion of everything, Victorian politicians, a never ending empirical hangover, delusional grandeur, white sliced bread, drizzle, and endless doubles entendres – and this is just the good stuff – it is, to all intents and purposes, illegal to not like The Kinks.

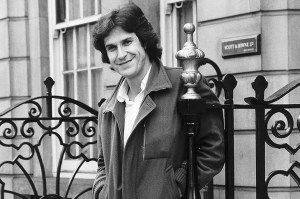

If Raymond Douglas Davies were to drop dead (and I wish him many more years to bestride his beloved and hated north London), a state of national mourning would surely, and quite rightly, be declared. Given the aforementioned list of national tropes, it should be no surprise that The Kinks and Ray Davies are a national institution as much as any old Queen Mum you’d care to name. And yet, given all that, there is still a critical sniffiness that The Kinks were, compared to the big Brit visionary three of the Sixties – The Fabs, The Stones, The Who – the ugly ducklings, or even the runts of the litter.

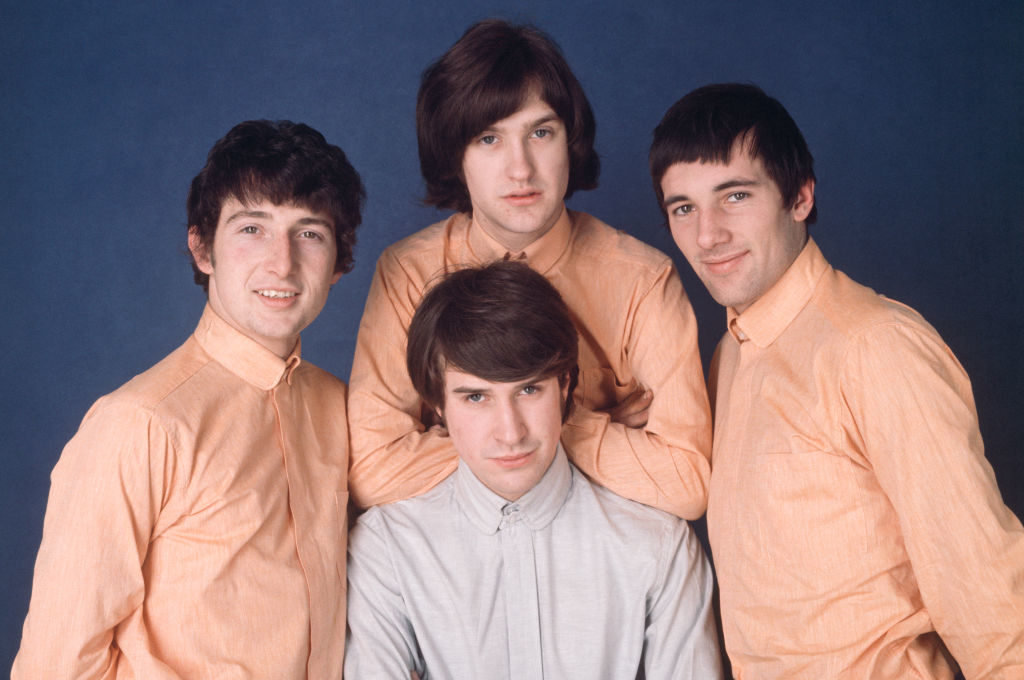

By November 1968, The Kinks had not had a top ten hit single for nine months, since ‘Autumn Almanac’. Their last album, the extremely groovy Something Else, had been a relative flop. In short 1968, the year of revolution, dope, and ‘fucking in the streets’, was probably not the best time to release a concept album about a lost mythical England that may have been a nostalgic dream or a contemptuous nightmare, depending on your reading of it. Or, as Ray Davies said, ‘I went into my own Wizard of Oz land.’

Older brother Ray was the pop hit machine, and younger brother Dave (17 years old when ‘You Really Got Me’ was released) was the Beau Brummel dandy yobbo. If it wasn’t enough that Ray and Dave’s sibling rivalry frequently broke into violence, Dave and drummer Mick Avory also hated each other. It all came to a head at a show in Sweden when Dave, brilliantly, advised Mick that the drums would sound better if he played them ‘with his cock’.

Mick considered Dave’s musicianly advice for a moment, then promptly attacked him with a cymbal. So much blood was shed that Mick, thinking that he had actually killed the younger Davies brother, went on the run. Needless to say Dave survived, as did The Kinks. Just.

To say that The Kinks were calamitous would be an understatement. Unlike The Beatles, they had no Brian Epstein to try and steer them through the wilds of the newly-invented music business. Instead, they got an upper-class nitwit chancer called Robert Wace and his nitwit stockbroker pal Grenville Collins to steer them full sail into an iceberg. Prior to the recording of Village Green, the hapless Wace and Collins booked their ruffian charges on a package tour of the UK. The hitless Kinks were on the chicken-in-the-basket circuit, served up as yesterdays cold-cuts, abandoned by the teenyboppers who were now wetting themselves over The Herd.

The Who, those other rough boy London visionaries, were in a similar hitless hole but, unlike The Kinks, their career was rescued by the new lucrative American concert circuit. Banned from touring the States due to a complicated musicians’ union clause, The Kinks didn’t have the US option. So here they stayed, in rainy old England, with no flowers in their hair, strumming Ray’s dreamy lullabies to the English village of an imaginary yesteryear.

And what songs they are. The manifesto is intact from the start: ‘We are the Custard Pie Appreciation Consortium / God save the George Cross and all those who were awarded them,’ chirp Ray ’n’ Dave harmoniously on the 24-carat classic title track, a mere two decades after World War Two had ended, and 50 years before a demented and narrow majority voted the UK out of the EU, driving the whole broken wagon over the cliff edge in the process. ‘Preserving the old ways from being abused, protecting the new ways for me and for you,’ sang the brothers Davies – the most accurate prediction in all of rock ’n’ roll.

It’s all here, utterly in chime with the times we live in. ‘Do you remember Walter?’, the childhood friend who’s now grown up and ‘in bed by half-past eight’. I do, and now unfortunately he’s in touch with me on Facebook. When John Genzale took ‘Johnny Thunder’, Ray’s comic-book hero, as his name when he became a New York Doll, he created the tedious junkie outlaw prototype that remains a rock blueprint to this day.

And what of the people in ‘Picture Book’, who ‘take pictures of each other, just to prove that they even existed’? Well, they’ve stopped taken pictures of each other, they just take pictures of themselves now, all day long. Best of all is ‘Village Green’, Ray’s truncated hymnal version of the title track.

‘I miss the village green, and all the simple people,’ hisses brother Ray. This is the moment when I knew that The Village Green Preservation Act was no nostalgia show for Merry Olde England; it was, to my mind, a stark mockery of the provincial, dreary, conservatism that dear old Blighty seems incapable of breaking away from.

Of course, Village Green… went down like a brick budgie upon its initial release, despite some good reviews. The next album, 1969’s brilliant Arthur (Or The Decline and Fall of the British Empire) was as conceptually up the ying yang as its predecessor. Seemingly undaunted, The Kinks happily splashed around in the wilderness of the late Sixties, even finding time to soundtrack a terrible film, Percy (1970), about a man having a penis transplant. Whether this had any bearing on 1971’s career-saving proto-trans smash hit ‘Lola’ is not known. What is known is that The Kinks spent the rest of the Seventies becoming a much-loved stadium rock band when they finally were allowed into the United States.

Where did The Kinks slightly runtish reputation come from? Well, perhaps no other band has had their back catalogue butchered and tossed away so appallingly. Throughout the Eighties, in the UK at least, you could barely pick up any of The Kinks classic Sixties albums. The only way you could score yourself a piece of prime period Kinks was to buy a sloppy budget cassette hits compilation. Not until the early Nineties did cheapo label Castle Communications start putting out the old Pye albums, a mere quarter of a decade after their initial releases. The Kinks’s reputation received a massive boost through the awful Britpop years of the mid-Nineties but, while the albums got the reissues and attention they had deserved for years, it’s less clear whether Ray Davies got much from endless name-checks by adoring disciples barely fit to tie his songwriting bootlaces.

So what do you get in this monolithic coffin of a box set? Well, if you don’t need to feed your kids, or pay off the divorce, then you get around four tonnes of vinyl and six tonnes of CDs. A Kinks wind-break, a year’s supply of cat food with Mick Avory’s face on it, a T-shirt bearing the legend ‘Why don’t you play it with your cock? It might sound better sound better’, and a life size model of The Archway Tavern. If you really get off on mono/stereo comparisons, buy the super-deluxe version of Village Green Appreciation Society. But you could do worse than buy the more affordable two-CD release – which has all the unreleased tracks on it anyway.

And how does it sound? As my main gig is as a musician, I can tell you exactly how it sounds. The remastering is one of the best jobs I’ve heard in a long while. There has been a reliable 5k boost on the high-mid end. Most importantly, the compression is lighter than on any previous mixes, and an expander has clearly been deployed, giving the whole sonic picture more presence. The vocal harmonies have more clarity. Crucially, none of Mick Avory and Dave Davies’s insolent instrument ‘bashing’ has been lost – preserving Village Green’s undercurrent of malevolence, which I have loved for over three decades, man and boy.

There is only one thing wrong with the 50th Anniversary edition of this wonderful album, and that is that it is all too prescient. The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society was no mere nostalgia trip. It has become a state of the nation address. The modern UK is not ‘sitting in a rainbow’. We are sitting on the bus, the Big Sky looks down on us, as we watch the drizzle through the steamed up windows, waiting to go over the precipice. ‘Preserving the old ways from being abused / For me and for you / What more can we do?’

Luke Haines is an English musician and author.