This article is in

The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.

The arts in America are dying. In the 20th century, Americans defined the world’s popular culture, but the 21st century world has no need of America’s arts. Through technology transfer, the world entertains itself with knock offs like Bollywood and K-Pop. In the 20th century, Americans created a new art form in jazz and its derivatives, and turned Hollywood into the world’s dream factory. In the 21st century, African American music has collapsed into monotone misogyny, and digital sex (see Julie Bindel) is America’s real movie business. Americans are in the gutter, looking up at porn stars. And the rest of the world is barely looking, or listening, or reading at all.

Consider the occasional moments when the arts made the papers this summer. The major events in the republic of letters were the death of Toni Morrison, who leaves no obvious inheritor in African American fiction; and the pulping of a history book by Naomi Wolf when her publishers discovered that key parts of it were false. The big ticket at the movies was Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, a long sob of nostalgia for the late Sixties, when men ran Hollywood, women were on the pill and Sharon Tate was still alive.

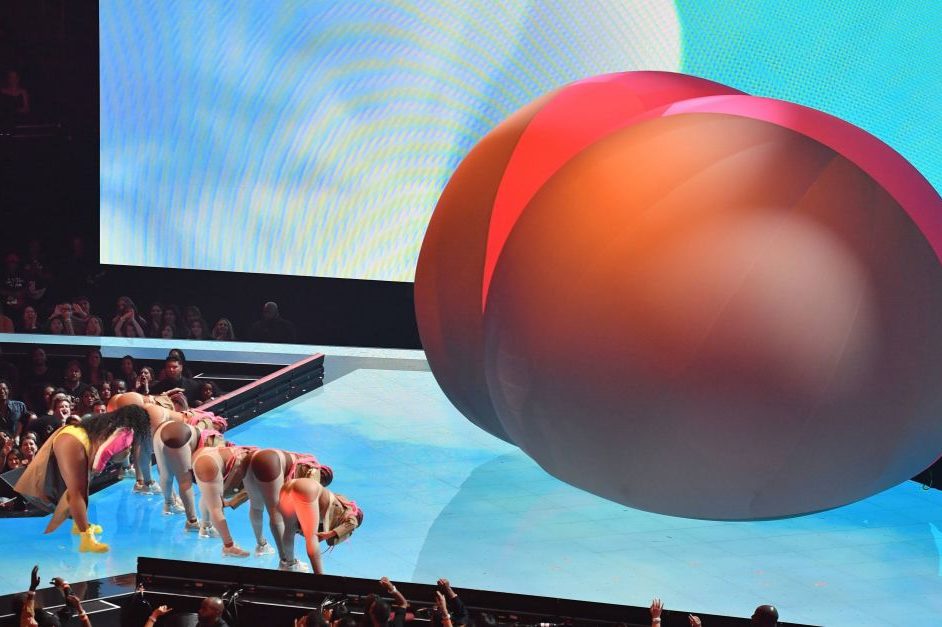

Everything is derivative and nostalgic. Nothing of note happened in painting or dance — or criticism, because the task of the American critic is to write obituaries and rewrite press releases. In music, Taylor Swift, once the Great White Hope of a dying industry, emitted a scrupulously bland album by committee. The jazz album of the year was, as it was last year, a studio off cut from John Coltrane, who died in 1967. The show, or what remained of it, was stolen by Lizzo, an obese but self-affirming squawker who, befitting an age of irony and multi-tasking, is the first person to twerk and play the flute at the same time. Meanwhile at the Alamo of high culture, 87-year-old John Williams marked the Tanglewood Festival’s 80th anniversary by perpetrating selections from Star Wars and Saving Private Ryan for an audience of equally geriatric and tasteless boomers.

In a dying culture, the best cases, like Wynton Marsalis and Bob Dylan in music, are curators of the Museum of American Greatness. The worst reflect a spiral into coarse nostalgia, as the needle wears out the groove: Stadium Country, Quentin Tarantino, the decay of fiction into self-help and affirmative action. The worst of all subordinate aesthetic values to political dogma, which is why it’s an offense to point out that the decline from Duke Ellington and Aretha Franklin to A$AP Rocky and Lizzo is a slide from civilization to barbarism.

***

From the late Twenties to the early Eighties, Louis Armstrong’s ‘Struttin’ With Some Barbecue’ to Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’, American popular art ruled the world. Its method was to assimilate immigrant influences and the arts of Europe. The blues coalesced from the glossing of African and Spanish rhythms with the harmonies and formats of the English hymnal. Debussy and Ravel were the unacknowledged masters of jazz harmony, French novelists the pre-cursors to Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and German Expressionist movies and Mahler symphonies the wellsprings of film noir and its soundtracks.

This assimilatory technique was so powerful that after 1945, Walt Whitman’s prophesy of a democratic high culture seemed to be fulfilled. In literature, the Great American Novel was issued annually, the obscurities of French Romantic satanisme installed in the college system by the Beat poets. In painting, the Abstract Expressionists domesticated the pre-War European styles of Cubism and Surrealism, then exported them at scale as international modernism. In music, Americans covered the waterfront, from the popular styles of Elvis, Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis; to avant-garde Miles Davis and aspirational Frank Sinatra; and even to Leonard Bernstein, who made up in enthusiasm what he lacked in talent, and Aaron Copland, who raised the barn that Dvorak built.

In the Sixties, mass media intensified the exchanges between America and Europe. Dylan freed Lennon and McCartney from ‘moon and June’ platitudes, but Lennon and McCartney freed rock’s lone virtuoso, Jimi Hendrix, from the loop of the blues. The infiltration of French and Italian cinema, and the invention of Film Studies, seeded the imaginations of Scorsese and Coppola. Pop art, invented in England in the Fifties, conquered the boardrooms and bedrooms of Madison Avenue. In the Seventies, the Americans pulled ahead: disco and Philly soul, Iggy Pop and the Ramones, Mean Streets and The Godfather, the extension of Europe’s modernist literature by the American Jewish firm of Bellow, Roth & Co.

And then, around the time that the Iranian hostage rescue went into the sand, it stopped. Or rather, the machinery kept pumping, but the quality of the product now varied from grandiose failure (Apocalypse Now, the novels of Thomas Pynchon) to cynical trash (the faux-soul of Michael Jackson). By the mid-Eighties, the union between popular aspiration and elitist excellence, the Lyceum and the Library of America, had dissolved. This, and not the complexities of the Cold War or the iniquity of the military-industrial complex, explains why neither Francis Ford Coppola nor Oliver Stone nor Stanley Kubrick could make a truly great Vietnam movie.

The arts are quarantined on campus, where the highest common denominator is theoretical pretension, and where no art of any worth is ever made. Entertainment is ghettoized on the internet, where the lowest common denominator, and the only sure way to make money, is sex and violence, and the even surer way is to combine sex and violence in the same image. No more Jackson Pollock and Elvis Presley. Today, the world looks to American ‘art’ only for pimps and porn — the imagery of slavery.

***

What went wrong? The usual suspects are mass production and homogenization — capitalism, basically. The commercial reality is that in show business, there is no show without the business. Still, though the synthesizer’s effect on pop music was akin to that of the Spinning Jenny on artisanal weaving, modern democratic art was always geared to the machine. Technology created the media — the three-minute single, the live broadcast, the electric guitar, the synhesizer and the digital camera. And though digitization wrecked the copyright system that had sustained artists since Beethoven’s day, it’s also true that every artist since Beethoven has also been a commercial entrepreneur.

The failure of the democratic arts since the Eighties was, like the halving of NASA’s budget in the decade between the Moon landing and Reagan’s first term, a failure of imagination. The sources of America’s 20th-century artistic imagination were: Old World precedents; the democratic aspiration that New World self-educators could outdo the Old World aristocracies; and the mixing of ethnic ideas and motifs in the free market. By 1980, all three of these streams were drying up or, in a spectacular case of self-harm, were being diverted and dammed.

The idea that Americans could educate their own sensibilities to international standards lasted little longer than Emerson and Whitman. By the late 1800s, the United States had adopted a university system along German lines, and ambitious Americans were funneling themselves into its specializing disciplines. By the early Sixties, University of California administrators were boasting that they had created a ‘multiversity’ geared to the needs of technocracy, while University of California students were rioting about an alleged lack of free speech.

By the end of the Sixties, students and administrators had arrived at a Westphalian peace. The students permitted the university to stay in the business of training specialists and technicians. The university let the students redefine the humanistic curriculum. Henceforth, the purpose of liberal education was to prevent the education of classical liberals.

In the new age of identity politics, Americanization had to be reverse-engineered, the glorious miscegenation returned to pure essences. No more mingling of Debussy and Gershwin, or Gershwin and Louis Armstrong in the marketplace of musical ideas. No more mingling of European high culture in impressionable American minds. The arts served to confirm political principles. As Soviet film-makers had cranked out propaganda about tractors and steel, so American teachers vouched for provincial mediocrities like Frida Kahlo and Alice Walker. In subsequent decades, these brave innovations filtered into school syllabi.

The idea was to turn the culturally patriotic melting-pot into a radical rainbow coalition. The result, as we know, was Bill Clinton on sax, a collapse in Humanities enrollments in colleges, and the production of historical illiteracy on a scale not seen since the Roman empire went south.

Today, almost all young Americans have no idea how an English-speaking liberal civilization came to be where it is, on the wrong side of the Atlantic; or what its artistic achievements are; or what its current purpose might be. The greatest American novels, Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer, are banned from schools as ‘racist’. The unique American arts of popular music aren’t taught as music, but as a species of African American affirmation. The study of cinema, bizarrely, is reserved for college, by which time most of the students can read a book.

The boomers were educated in Western Civ, ‘great books’ and all, but they cut the cultural cord as well as the link between generations. As the people who declared Jefferson’s ‘sovereignty of the living generation’ are dying off, they leave a desert of politicized mediocrity. The world has taken enough from American culture to pastiche it in Bollywood or K-Pop, but it has dropped the ideals of democracy and excellence. In geopolitics, the United States is becoming marginal to Eurasia. Culturally, it’s already happened. The world used to admire Americans as a can-do people, but the culture that defined the world’s popular art in the 20th century cannot even reproduce itself.

In the dog days of summer, a tremor of self-knowledge flickered across the remaining arts pages of America’s remaining magazines. The Atlantic claimed that Walt Whitman was America’s essential poet, but National Review condemned him as the aesthetic ancestor of the Kardashians. The answer, of course, is that Whitman is both — and that is the tragedy of the arts in America today. The materials of popular art have never before been so accessible, thanks to the internet, but the educational infrastructure has never been so obstructive, the commercial odds so high, or public ignorance so carefully cultivated by the state. The first civilization to dispense with the arts, America is now an experiment in barbarian democracy. Only Hollywood has happy endings.

This article is in The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.