Visiting public art galleries has become a dangerous undertaking — at least if one wishes not to be accosted by ludicrously woke signage and unnecessary trigger warnings. In the past, one might have, justifiably, seen warnings before entering a room exhibiting, say, the garish and pornographic sculptures and photos of Jeff Koons going hard at it with Hungarian-Italian “actress” and part-time politician Ilona Staller, aka Cicciolina. Today, such warnings are found outside galleries exhibiting not such ephemera but the greatest works in the Western canon.

Last autumn’s Titian show at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston warned visitors before entering that “Titian: Women, Myth and Power explores themes of sexual assault and violence.” The woke infestation of great galleries began in the United States, but it is a disease that has been caught, and caught badly, by the art museums in London. Alas, no “world-beating” vaccine yet lies at hand.

Tate Britain, the UK’s premier gallery of British art, a short walk from where I live in central London, is very stricken. It has closed its proper restaurant, once known for its excellent and well-priced wine list, due to the apparent offensiveness of the decor: “Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats,” a mural encompassing all four walls by the decorative painter Rex Whistler, after whom the restaurant is named. When it first opened in 1927 it was described as “the most amusing room in Britain.” During Tate Britain’s £45 million rejuvenation in 2013, the mural was extensively restored — an action which the museum made much of in its report for that year.

The money spent on the restoration was wasted. Those needing a sit-down lunch and a decent glass of wine after a busy morning viewing Tate’s unsurpassed collection of Constables, Gainsboroughs, Turners and Pre-Raphaelites are now confronted by a sign saying “The Rex Whistler Restaurant will remain closed until further notice.”

The reason? In one corner of the mural — a clearly mythical landscape of hunters, nymphs and satyrs — is a black slave boy with a chain round his neck. The Tate’s ethics committee has pronounced that “the imagery of the work is offensive.” Apparently the offense is made much more egregious due to the fact that plump, prosperous, middle-aged white people might be eating in front of it. Clearly, a mere trigger warning will not suffice. While we await a final decision on its fate from the museum, the restaurant remains closed and there seems little prospect of it ever reopening.

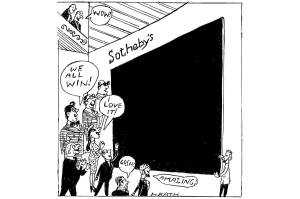

Tate Britain is currently host to two major temporary exhibitions. One is Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950 to Now; the other is Hogarth and Europe. The exhibition of British-Caribbean art is an unalloyed celebration of artists previously marginalized by mainstream cultural institutions — and no complaints there. But one might hope that the exhibition devoted to Hogarth, Britain’s greatest ever cartoonist (indeed the founder of the lampooning, cartooning tradition so important in the Anglo-American world) and one of the most important portraitists of the eighteenth century, would have been cause for a similar celebration. Not a bit of it.

“This exhibition contains derogatory representations of race, gender and disability, and addresses themes of racial and sexual violence,” an official sign proclaims as you enter the Hogarth show. It goes downhill from there. The paintings remain what they have always been — among the finest made in eighteenth-century Britain — but the commentary verges on self-parody.

Art historians have traditionally viewed Hogarth as a uniquely British artist with a peculiarly British sensibility. Hogarth frequently mocked the collectors of his day, as more interested in second-rate, old-fashioned Continental paintings than in his own works or those of his English contemporaries. The exhibition seeks to show that European artists such as Canaletto, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin and Guiseppe Maria Crespi were also making social commentary along Hogarthian lines in their paintings. The trouble is that none of their efforts — at least none displayed in this exhibition — comes close to being as amusing and sharp as Hogarth’s Modern Moral series, including “The Rake’s Progress” and “Marriage A-la-Mode.”

Exhibitions such as this are a long time in the planning. Surely this one originated amid the raging debates on Britain’s exit from the European Union. The show intends to demonstrate that even an artist as British as Hogarth owed much to Europe — and Europe also learned from him, with perhaps the none too subtle subtext that even an artist as Brexity as Hogarth would not, could not, have been anything as vulgar as a Brexiteer. But politics moves on, and by the opening of the show in November 2021 Brexit had happened and was much less an issue of daily debate in the UK. Black Lives Matter was, of course, much more the thing. So the curators came up with the idea of getting various commentators to write up their thoughts to accompany the paintings.

The commentaries broadly fall into two categories. The first are wall texts that show Hogarth, even at his most nationalistic, in deep conversation with Europe. Hogarth’s most anti-French painting is surely “O The Roast Beef of Old England (The Gate of Calais)” — Calais was English-ruled until 1558 — in which hungry Frenchmen salivate over a huge haunch of beef brought over by British visitors; a Catholic priest is the only well-fed Continental. The picture is described as jingoistic — and it certainly is. Yet there is a pictorial and imaginative debt owed to Europe: “the painterly rendering of the beef echoes still life paintings of French artist Jean-Siméon Chardin.” It is not just that the Brits can’t cook without plagiarizing the French: apparently, they can’t even paint a side of meat without nicking ideas from across the Channel.

The other type of caption is rather more ludicrous: one that finds racism in the most unlikely of places. “Southwark Fair” wonderfully illustrates the types of entertainment one might find at an eighteenth-century market. A black boy is playing a trumpet; behind him at some distance is a dog dressed up as a man and walking upright on its hind legs. Alice Insley and Martin Myrone, the show’s curators, opine: “While mocking social class, the dog also makes a racist juxtaposition with the trumpeter, signaling deepening ideas of racial difference in eighteenth-century culture. Above all this chaos flies a Union Jack.” Where Britain’s flag is seen, racism can’t be far behind.

This kind of commentary reaches its apogee with Sonia Barrett, a self-styled visual artist and sculptor. Her biography reads: “Barrett’s practice centers on people, place and object-based commodification, performing furniture [sic] to explore themes of race and gender.” Barrett’s thoughts appear next to a self-portrait of Hogarth performing furniture by sitting on a mahogany chair (“Self-Portrait Painting the Comic Muse” 1757-58). “The chair is made from timbers shipped from the colonies, via routes which also shipped enslaved people,” Barrett writes. “Could the chair also stand in for all those unnamed black and brown people enabling the society that supports his vigorous creativity?” In a word, no.

Hogarth’s sensibilities might not be everything we want out of 2022. This is hardly surprising: he was, after all, an eighteenth-century artist. The work that the curators seem to think nails down Hogarth’s racism is a rather obscure, mediocre print called “The Discovery” (1743), which shows three friends surprising a fourth who is about to go to bed with a black prostitute. In fact, the picture’s history puts that racism into serious question. Ronald Paulson, in his magisterial Hogarth’s Graphic Works (1989), describes the print as probably relating to a long-forgotten incident involving one of Hogarth’s fellow members of the Sublime Society of Beefsteaks. As Paulson shows, Hogarth was dissatisfied with the work’s imagery and attempted to limit its circulation drastically. The plate was later destroyed by his widow. So the most offensive picture the curators could find was actively suppressed by Hogarth himself.

British public galleries owe a lot to American imports: some of their most generous benefactors, including John Paul Getty, Jr. and the much-maligned Sackler family, have been Americans. But one American export they can certainly do without is wokeness. Sadly, I fear it is here to stay.

Hogarth and Europe is on view at Tate Britain until March 20, 2022. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2022 World edition.