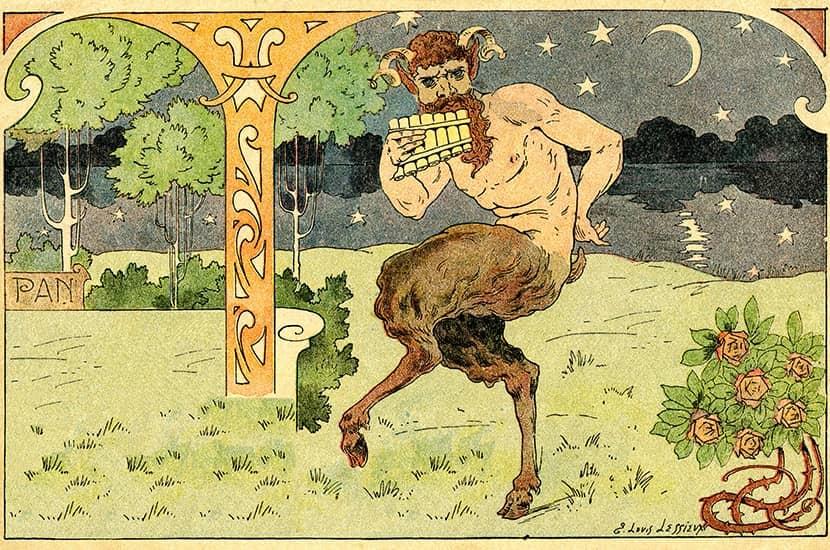

Pan’s name is thought to derive from “paean,” the ancient Greek verb meaning “to pasture.” His half-man, half-goat form reflected his role in protecting flocks of goats and those who herded them among the wild hills of Arcadia. Panic was his superpower, freaking out mortals in the woods with distorted sounds, even neutralizing hostile armies.

This might seem like an adequate portfolio of godly aspects, but, as Paul Robichaud demonstrates in Pan: The Great God’s Modern Return, it didn’t take long for things to get more complicated. The Homeric “Hymn to Pan” had a slightly different story, which was that the strange goat-child, rejected by its earthly nurse, got taken in by all the gods instead, and they named him Pan, or “all.” In this accident of language, each of his name’s two meanings created a distinct version of who Pan was and what he stood for.

The Orphic cult saw the “all” of Pan as the genesis of the four elements that made up the material world; the Stoics argued that his part-goat, part-human form reflected the domains of earth and reason. Pan’s meaning accordingly turned cosmic. The announcement of Pan’s death on a ship headed to Italy — news that prompted the emperor Tiberius to call for an inquiry —might have been a second linguistic accident, in which a ceremonial lament of the death of another god was mistaken homophonically for Pan’s.

The flexibility of meaning afforded by Pan’s multitude of identities would later enable him to be incorporated as a reimagined proto-Christ in Renaissance and Restoration culture. Pan died, and so did Christ; because Pan meant “all,” and Christ was the all, Pan was legit, and could exist in all his goat-headed glory. These theological gymnastics are all the more impressive for Pan’s persistent horniness, in all senses: the goat-horns on his head, his protuberant genitals and his distinctly problematic predatory tendencies towards maenads and, depending on who you believe, the Moon.

Later, romantic nostalgia for a wilder pagan world invoked a version of Pan as defender of nature. This Pan was formless, an idea more than a figure, or he was lamented as dead. Pan’s death was symbolic of the demise of the pre-modern culture that birthed pagan mythology; to lose this was to lose enchantment. And yet the terror and awe of the romantic sublime looks suspiciously like Panic — a dark enchantment of its own, the shadow side of ecstasy.

This chasing of enchantment would enter a new era with fin-de-siècle occultism. While we tend to imagine the Pan-like form of Satan as a result of the early Church’s sidelining of pagan godheads into demonic inadmissibility, Robichaud instead traces the elision of goat-god and devil to the iconic illustration of “The Baphomet of Mendes” by the 19th-century occultist Éliphas Lévi. For Lévi, Baphomet was Pantheos, the Absolute in iconic form, winged and goat-headed with a pentagram embossed between his horns, female-breasted and sitting meditatively with crossed legs and outstretched arms. Lévi’s Baphomet went viral: his bronze statue continues to be unveiled from time to time by the Satanic Temple outside US courthouses to protest the selective application of freedom of speech and religion.

The magickal communities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries went wild for this new, countercultural version of Pan. Beast-affiliated Aleister Crowley wrote bad poetry in attempts to summon Pan in order to become him; no doubt the licentiousness of pagan gods was part of the attraction too, allowing occultists to graze on a candy-shop-style array of quasi-theological identities, each with its own libertine pleasures.

The story of Pan sometimes looks like apophenia, the attribution of meaning to unconnected things, writ large. It does make you wonder whether there’s a tendency for adherents to any given icon to argue for its universality, one that can easily enough be read into the accommodating messiness of the outside world. As Robichaud tracks Pan through time, it turns out, for example, that 20th- and 21st-century depth psychology is notably talented at this, finding Pan variously in existential dread, sexual activity and the Iraq war. But perhaps this is an ancient problem: as soon as Pan was associated with the all, he was in danger of being identifiable as nothing in particular.

The panic-inducing randy goat archetype comes across as the Pan more congruent with the Arcadian pastoral world as it must once have been — one of dark forests, dangerous beasts and lust; of a Nature with the capacity to inflict fear rather than pity. Robichaud’s skill is in weaving a coherent path through all this, setting out his material with scholarly specificity. It is a fascinating account of a strange god with meme-like reach across the ages, and a study in the temporal shape-shifting of mythology itself.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.