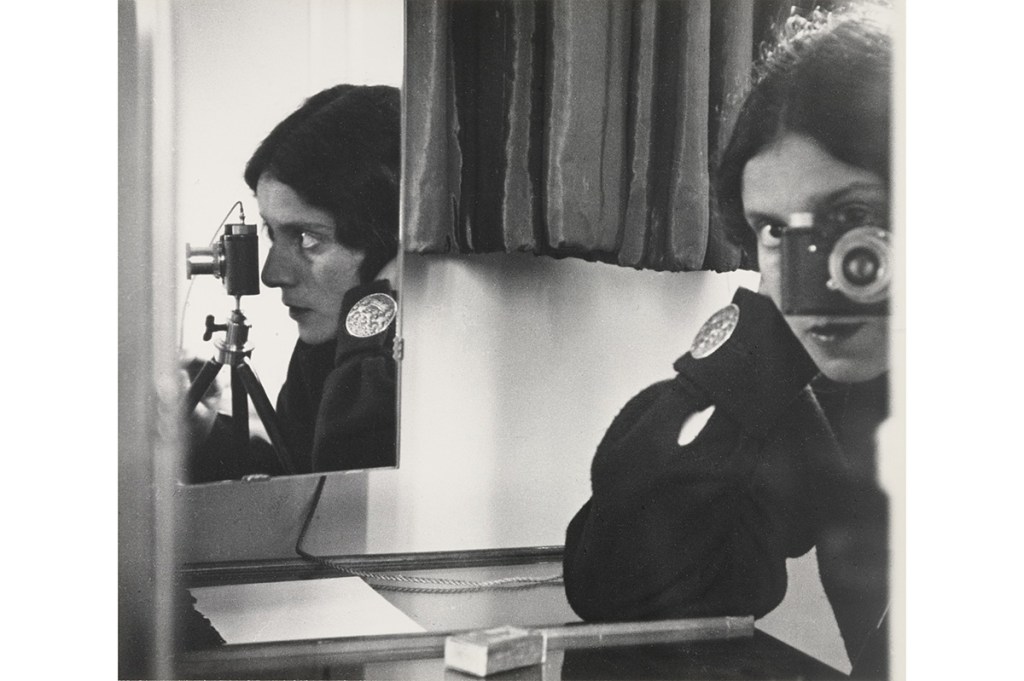

We are familiar with Dorothea Lange’s gritty photographs of Okies during the Dust Bowl. New Woman Behind the Camera, which opens this month at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, showcases Lange alongside over 120 other female photographers who refashioned modernist photography in the same years.

Photography developed through an ambivalent relationship to high art: the camera was often seen as a medium for journalism or advertising. Yet the modernist works here showcase the flexibility of the form. Still, there are inherent tensions in an exhibit like this. Georgia O’Keeffe once declined an invitation to be included in an exhibit of ‘women artists’: she wanted to be seen as competing with the best, not as part of an inferior subgroup.

It’s easy to forget how even major 20th-century female photographers tended to be overlooked at the time. When Diane Arbus died in 1971, she did not receive an obituary in the New York Times. (She finally received an obituary in 2018, nearly 50 years after her death, as part of the Times’s ‘Overlooked’ project). Lee Miller only received a brief obituary in the Times when she died in 1977, and that was as Lady Penrose, the wife of the Surrealist and museum director Roland Penrose.

Of the artists featured here Lee Miller, Dorothea Lange and Berenice Abbott will be the most familiar, but their counterparts from other countries offer a useful context. They were women working in the same medium in the same decades, yet they worked in different styles and under different cultural pressures. This makes for a very effective exhibition.

New Woman brings together the whimsical and the confrontational to show how modernism shaped photography. By the mid- 20th century, women photographers were working across genres from reportage to fashion advertising to high art. Here we see strikingly immediate images of major midcentury events such as Mao’s Long March and Gandhi’s funeral procession. The female subjects show different interpretations of the female form: women as models, muses and dynamic agents. I am haunted by Constance Stuart Larrabee’s untitled photograph from 1944: a Frenchwoman, accused of being a Nazi collaborator, holds the hair that has just been shaved from her head.

We also see female artists putting a different spin on domestic themes. Olive Cotton’s ‘Tea Cup Ballet’ (1935) and Věra Gabrielová’s ‘Untitled (Spoons)’ (1935- 36) use regular domestic objects, but in new ways. Cotton sets a tea set from Woolworths in a dramatically lit tableau as a choreographed scene. Gabrielová’s spoons lie at right angles to each other, like a geometric print. The domestic items are shown as duplicates of industrialized production, like the photograph itself.

But we also have the lighthearted and intriguing among this collection. Consider the arresting double exposure of Wanda Wulz’s ‘Io + Gatto’ (1932), an experimental work from the Italian Futurist movement. Wulz blends her own face with that of a cat, prefiguring many of the ‘transformation’ images of 20th-century science fiction movies. The result is beautiful yet troubling. So is Charlotte Rudolph’s vivid action shot of the German dancer Gret Palucca in 1925, the year Palucca first opened her dance school in Dresden. We see Palucca’s barefoot athleticism, and the movement of the expressionist dance style she pioneered. Palucca doesn’t engage with the camera; she seems caught in her own reverie of rhythm. We know what is to come (Nazi persecution, the closure of her dance schools due to her Jewish heritage), but in this moment she is caught on the brink of success.

Beyond these avant-garde images, New Woman also explores photography’s commercial possibilities, as shown in Genevieve Naylor’s image of two models in swimsuits from 1946. The model at the center of the photograph leans casually, looking at something in the distance we can’t see. Her smooth skin contrasts with the jagged volcanic rock beside her. Her body is angles as much as curves, a jutting-hipped rejection of the Jacques Fath silhouette that was making its way through fashion that year. Meanwhile her elbow points us to the other, kneeling model, who also sports a belted (and possibly uncomfortable woolen) swimsuit.

We don’t know the extent to which the artists in this show would have identified themselves as New Women in social and political forums. Simply having been alive between the 1920s and the 1950s seems insufficient. The New Woman was supposed to represent modernity — a respectable, educated modernity unlike that of her fast younger sister, the flapper or Modern Girl. But the phrase ‘new woman behind the camera’ also implies that there was once an old woman behind the camera too, and recalls that pioneering first generation of female photographers such as Julia Margaret Cameron and Gertrude Käsebier.

New Woman Behind the Camera can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City from July 2 to October 3, and then at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC from October 31.