Paintings so nice you’ll see them twice. That’s the gambit of Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, the gargantuan ‘simultaneous retrospective’ that’s currently split between the Philadelphia Museum of Art and New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art.

OK, so the concurrent presentations of painting and sculpture by the neo-Dada, quasi-proto-Pop artist aren’t exactly duplicates. The museums promise a sort of imperfect symmetry: ‘each half of the exhibition will act as a reflection of the other, inviting viewers to look closely to discover the themes, methods, and coded visual language that echo across the two venues’. The idea was to divvy up the spoils of John’s six-decade-plus career so that a visitor to one show or the other comes away with a coherent idea of the artist’s story, while the intrepid devotee is rewarded for traveling to both. For the 91-year-old Johns, it’s nothing short of a triumphal march down the I-95 corridor.

Few living artists, if any, could conceivably garner this sort of double blessing from two of the country’s most prestigious museums. Whether any merits the honor is a different question. Do we really need so much Jasper Johns? At this exorbitant scale, the production becomes partly an exercise in self-justification.

Johns is a darling of the elite institutional art world and has been for over 60 years. His signal accomplishment was helping wrest New York from the grip of Abstract Expressionism’s soul-bearing self-importance in the late 1950s, replacing it with a more literalist, deadpan approach that must have seemed refreshing at the time. The creation myth goes something like this:

In 1954, Johns was a 24-year-old South Carolinian trying his luck as a painter in downtown Manhattan, with vanguardist friends like composer John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham and fellow artist Robert Rauschenberg. One day Johns destroyed everything he had ever made. Soon thereafter, he says, he had a dream in which he was working at his easel, and the painting in front of him was of an American flag — not flapping in the wind but abstracted flat onto the picture plane. He got up the next morning and began doing it for real.

The basic idea behind that seminal work, ‘Flag’ — and behind the targets, numerals, letters, maps and other symbols that he’d use to make ensuing paintings and sculptures — is essentially a semiotic brainteaser: a painting of a flag is both a painting and a flag. Think of it as an extension of Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe in ‘The Treachery of Images’ (1929): This is and is not a flag. Get it? Good.

This was canny positioning, with a dash of Duchampian wit. Abstract Expressionism was losing steam, and Johns showed us a way out. His visual forms were not some esoteric manifestation of the internal soul. They were already public, bracingly banal and instantly recognizable — ‘things the mind already knows’, as Johns put it.

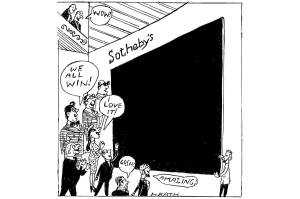

The paintings were shockingly well received. During and after a momentous first solo show at Leo Castelli’s fledgling gallery in 1958, influential collectors and powerbroker institutions like MoMA scooped up Johns’s work, kicking off a lifelong run of rising prices and continual museum support. To keep the game going Johns riffed endlessly on that same grab bag of symbols. His mantra: ‘Take an object. Do something to it. Do something else to it.’

For the initial ‘Flag’, Johns adopted a mottled, translucent, encaustic wax medium, in which he embalmed pigment and New York Daily News clippings to give our Stars and Stripes an uncanny tactility and surface intrigue. Encaustic collage became Johns’s signature look, but more invasive interventions followed, and these are on ample display in Philly and New York. Here Johns stacks three flags on top of one another, there he blanches his targets to monochrome white. Now this US map is in oil, now it’s a lithograph, now it’s a pencil drawing, now it’s a metal relief. Letters and numerals are arranged in a grid or superimposed on top of one another. The word ‘RED’ stenciled in blue paint; then ‘BLUE’ stenciled in red!

Like Rauschenberg, Johns sometimes augments his symbols with three-dimensional manufactured or found objects, dispatching his doting philosopher-critics on ever-wilder semantic goose chases. In ‘Watchman’ (1964), on view in Philadelphia, Johns takes the bottom half of a plaster-cast figure, sits him in a wooden chair, flips the whole ensemble over and affixes it to the canvas’s top right corner. Below and to the left, a painted streak of gray paint stops with an actual stick (as if it had dragged the pigment itself) leaning against a small ball, both resting on a plank of wood that doubles as the bottom edge of the painting’s frame.

Four years before Andy Warhol presented the facsimile Brillo boxes that Arthur Danto famously hailed as evidence of the ‘End of Art,’ Johns cast a pair of beer cans in bronze and painted them to look like the originals, selling them under the no-nonsense title ‘Painted Bronze (Ale Cans)’. Johns’s is a protean enterprise, clearly. At heart, however, the bulk of his artistic output scarcely amounts to more than monomaniacal recapitulation of that original Dadaist idea. This is nowhere more apparent than when it is exposed in an enormous retrospective such as this. Nihilistic repetition produces a joyless, sensibility-deadening effect.

Johns’s admirers argue that his sprightly brushwork and encaustic surfaces rescue his paintings from their elementary-school obviousness, endowing them with an equivocal sense of subjectivity, mystery and chance — all qualities connected to the Abstract Expressionist aesthetic that the ready-made motifs seem so plainly to reject. To my eyes the manner is more sprezzatura elegance: urbane and professional but ultimately as tedious as his subject matter. It’s cruise control stuff. Johns’s slick expressivity feels like a haughty pose, as if he were merely mocking those try-hard second-raters, ubiquitous in the 1950s, who contented themselves with making cheap de Kooning knockoffs despite lots of big-game talk. In this sense, his handling is yet another knowing wink to art-world insiders. Johns keeps it cool and declines to strive for anything greater.

‘What I wanted to do was find out what I did that other people didn’t, what I was that other people weren’t.’ This is how Johns described that revelatory moment in 1954 when he threw out everything he’d painted and began making flags, targets and the like. From the very beginning, the thing Jasper Johns aspired most to create was not great art, but ‘Jasper Johns’: an artistic identity all his own. Make it new; make it you.

Is it any wonder, then, that the flags became Johns, and Johns the flags? The affirmation of worldly success came instantly and effortlessly; there was no turning back. For a while, autosarcophagy was the only way forward: like a pharaoh in his pyramid, Johns seemed entombed forever in his own iconography. But he eventually began shaking things up, adding a degree of lexical and formal complexity to his paintings. In the mid-1980s, for instance, he made a cycle of the four ‘Seasons,’ an allegorical celebration of life turned inward and gloomy. Johns repeatedly traces the silhouette of his own shadow onto the canvases, integrating those forms into intricate collage-like compositions that also include arcane references to art history and natural flux.

As Johns passed through his eighth and ninth decades, he grew increasingly elegiac and more obviously concerned with mortality. An evocative recent series incorporates a 1965 Life magazine photograph in which James Farley, an anonymous young marine, shudders in inconsolable grief at the loss of a friend in Vietnam. ‘Farley Breaks Down’ (2014) and the paintings related to it are also some of the most formally interesting works on display, with their uncommonly nuanced greens puddling about on the plastic support. Ignore for a moment the painfully on-the-nose reference to army fatigue camo patterning and allow yourself to follow the artist as he simultaneously conjures and conceals his forms in unpredictable ways. If the early Johns buried his feelings under layers and layers of encaustic and irony, here he at last allows the poetic impulse to surface and run.

It goes without saying that these rare bright spots hardly vindicate the bipartite expanse of real estate given over to so much self-reflexive and, yes, redundant work. Johns is an important figure, if only because of his rock-solid stature within a hopelessly disarranged art world. The retrospective is a useful opportunity to examine just this, but it’s difficult to applaud the curatorial excess that’s displayed right there with the art itself.

Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art until February 13, 2022. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2021 World edition.