‘A is for Amy who fell down the stairs/ B is for Basil, assaulted by bears…’ The Gashlycrumb Tinies, an alphabet in dactylic couplets of the surreal fates visited on a succession of blameless tots, is probably Edward Gorey’s best-known work — and that work forms a pretty coherent whole. Dozens and dozens of tiny booklets, almost all intricately hand-crosshatched in black pen, darkly spoofing established genres, set in a Victorian-Edwardian world of sighing flappers, funerary urns and decaying stately homes. They are filled with surreal menace and random violence or moral horror — much of it offstage — and always played for laughs. The dreamlike, associative drift of Gorey’s work — is that an umbrella or a bat? — is linked by his biographer to the old surrealist game ‘Exquisite Corpse’. Well, quite.

Gorey has here and there been described as ‘Dr Seuss for Tim Burton fans’ and ‘the Charles Schulz of the macabre’, but he was in every way more wayward and interesting than that. He wrote almost impossible to classify little books — crunched-down Victorian novels — that seemed to belong in the children’s sections of bookshops but were quite unsuited to children, in whom he took little or no interest. He found a public only very slowly, and over many years — thanks, in large part, to till-point placement and Hello-Kitty-scale merchandising efforts by the Gotham Book Mart in New York.

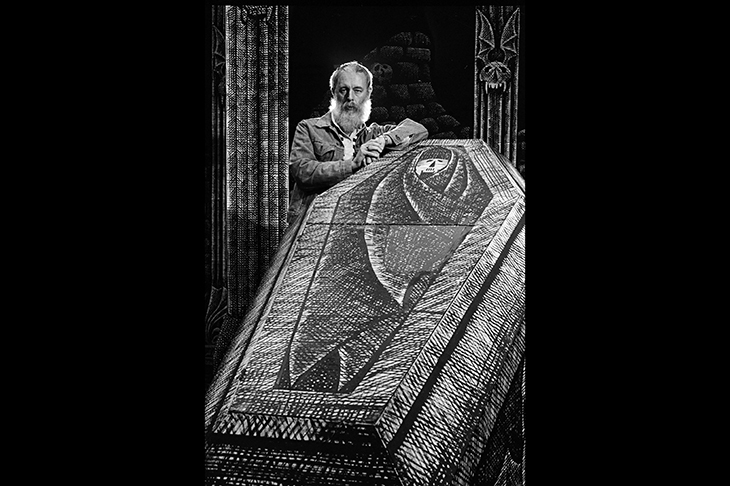

As a rough contemporary, Maurice Sendak, described it, Dr Seuss knew ‘how to satisfy the customer’, and Sendak had no inkling of how to satisfy the customer but managed anyway; but ‘Ted had no intention of satisfying the customer’. He got there in the end though — working brilliantly and with great success as a commercial illustrator of book jackets, and getting famous in his own right with the anthology Amphigorey and its successors, and then his showstopping designs for a Broadway production of Dracula. But he plowed his own death-haunted furrow. As he said at one point: ‘There is so little heartless work around. So I feel I am filling a small but necessary gap.’

You find yourself, as a reader, rummaging through Gorey’s life and mentally dividing things in it into two columns. The first is headed ‘Unexpectedly un-Goreyish’, and the second is headed — to use the modern slang — ‘Gorey AF’. The first column includes: owning a bright yellow VW Beetle, having a strongish midwestern accent, sometimes wearing shorts, hanging in his house a plaque that said ‘Home Is Where Your Cats Are’, cooking from Julia Child, and having a great fondness for Tintin comics and reruns of The Golden Girls.

Almost everything else — even, though it’s a marginal case, videotaping every single episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer — goes into the second column. He collected day-of-the-dead skulls, stones and Victorian postmortem photos (‘Any dead babies?’ was the cry at the postcard mart). As a child in Chicago he kept a pet alligator (this was not unusual at the time, but his cousin Joyce’s gloss on it, ‘You’d just put it in the canal when you were tired of it’, is very Goreyish). Poison ivy grew through a crack in the wall into his Cape Cod living room in later life. His apartment in Manhattan’s Murray Hill contained a mummy’s hand (‘It’s only a child’s,’ he told an interviewer) and a mummy’s head. He made a friend when someone dislocated his shoulder. He once accidentally flambeed his beard. Rumors circulated that he had two left hands.

And in his pomp Gorey played himself with great relish: tall, extravagantly bearded, ears pierced and hands bristling with rings, wearing a full-length fur coat and old-fashioned white sneakers, arch and epigrammatic in his conversation. Like his many extravagant pseudonyms, it was a game of display and evasion. Gorey had been a solitary and highly intelligent only child — raised by his mother and cousins after his parents’ divorce — who read very early and very widely and deeply. He doesn’t seem to have been a wholly happy man. He had intense and often collaborative friendships that would last a few years and then drift into indifference or hostility. He was tortured, a handful of times, by terrible unrequited crushes on unavailable men. But in the life, as in the work. ‘Irony,’ Mark Dery writes, ‘is what turns tragedy into black comedy in Gorey’s world.’

Gorey was, though it’s possible to belabor the paradoxes, a man of contradictions. We’re forever told he wasn’t a joiner, but he seems to have been (albeit with a certain reserve) extremely sociable. And he knew everyone. Through these pages flit (among others) Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Merrill Moore, William Carlos Williams, Dick Wilbur, Archibald MacLeish, Susan Sontag, Charlton Heston and Alison Lurie. He resisted the zeitgeist, but was part of it anyway.

And he was as gay as the bunting in a funeral home, but always claimed to be asexual and tended to pantomime a shuddering dismay at the actual business of fornication. He claimed at one point to have had a teenage sexual experience that put him off for life (‘It’s Gorey’s Rosebud moment,’ says Dery, rather more decisively than seems warranted, ‘the experience that made him who he was’). Yet he did spend time in gay bars, some of his stories and illustrations positively bristled with gay subtext (not to mention hidden sketches of penises), and he told Alison Lurie, when he was 28, that he felt he ‘ought to be having a few direct emotional experiences, however small’. And at another point he wrote: ‘I feel like a captive balloon, motionless between sky and earth. I want birds to bring me messages.’

Near-obsessively cleaving to routine seems to have been one of his bulwarks against the void. In later years he ate breakfast and lunch at the same diner (same breakfast, same lunch). He worked extraordinarily hard — just think of how many of his 75 years he must have spent cross-hatching! — and pursued his enthusiasms with the same focus. His library at his death comprised more than 21,000 volumes. He loved the movies, too, though it all went wrong, he thought, with the arrival of the talkies. And he was a complete balletomane — retreating to Cape Cod when the ballet wasn’t on, and retreating there for good when Balanchine (whom he compared to ‘God’) died. Even for someone with the 60-hour days a friend claimed of him, though, can he really have seen ‘as many as a thousand films a year’? Or gone to eight performances of the ballet a week? Perhaps he did not sleep. It’s worth noting, incidentally, that he hated Henry James, Christmas (‘really is a family holiday’), The Catcher in the Rye, brussels sprouts, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s work, and Robert Frost (who was the name he gave when asked ‘Who’s the biggest asshole you ever met?’).

His biographer, then, is offered a great boon: you get a great paragraph each time you straightfacedly precis one of his works.

Sometimes he makes use of Magritte’s hallucinatory conjunctions, as in The Prune People, in which prim, proper Edwardians with prunes for heads go matter-of-factly about their affairs. Or he imagines the inner lives of objects — a very surrealist thing to do — as in Les Passementeries Horribles, in which hapless Edwardians are menaced by ornamental tassels grown to monstrous size.

Or just quoting from the couplets to The Nursery Frieze: ‘Corposant, madrepore, ophicleide, paste/ Jequirity, tombola, sphagnum, distaste’; ‘Wapentake, orrery, aspic, mistrust,/ Ichor, ganosis, velleity, dust.’

There’s no question Dery knows the work extremely well, and has dug assiduously into the life. He’s struggled, a little, to organize his material. There’s a great deal of repetition in this book. We hear (correctly, but too often) how Gorey’s work absorbed or reflected Japanese influences (Noh, Kabuki, Hiroshige, Hokusai), surrealism and Dada, occultism, Edward Lear, Tenniel, Taoism, the aesthetic of silent film, Golden-Age crime, Ronald Firbank and Ivy Compton-Burnett, Victorian (and previous) morality literature, penny-dreadfuls and ballet. And sometimes, with his earnest Freudian or Derridean analyses and gushing superlatives (‘capstone’, ‘masterpiece’, ‘tour de force’ etc), you feel that Dery might be — as was said of critiquing Wodehouse — taking a spade to a soufflé.

His epigraph, Gorey said, ought to be ‘Oh the of it all.’ But he lies, accidentally, appropriately, in an unmarked grave. He was, I think, an exquisite but very minor genius — and at home with things not making sense. The Eleventh Episode ends:

‘Life is distracting, and uncertain,’

She said, and went to draw the curtain.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.