Pity the poor Drawing Center. Founded in 1977 — or, rather, “born into the petri dish of the SoHo art scene in the 1960s and 1970s” — the Center was the pet project of Martha Beck, a former curator at the Museum of Modern Art. She felt that the medium of drawing, being underserved by the arts establishment, needed its own specialized venue. Over the years, this downtown gallery has proved its mettle, mounting a variety of historical and contemporary exhibitions, as well as making a point of reaching out to working artists, some of whom later went on to greater recognition.

But that petri dish? It’s changed mightily since the heyday of industrial lofts rented on the cheap. Though painters and sculptors continue to work in SoHo, it’s no longer the fulcrum of the international art world. Real estate, as the truism has it, follows artists and, as a general rule, displaces them. Galleries are now few and far between in SoHo. As a result, the Drawing Center finds itself marooned among a bevy of luxury boutiques, high-end hotels, pricey eateries and, proving that some things never change, a noisome lineup of traffic going into the Holland Tunnel.

Will culture mavens think twice, then, about going to SoHo or, as an acquaintance put it, “the boonies?” It would be a shame if that’s the case, otherwise they might miss The Clamor of Ornament: Exchange, Power, and Joy from the Fifteenth Century to the Present, a knockout exhibition curated by Emily King, a London-based historian and curator. Bringing together more than two hundred objects that range the world over, King, along with co-curators Margaret Anne Logan and Duncan Tomlin, seek to underline how ornament can be not only “a means of exchange across geographies and cultures,” but the basis for “pleasurable disruption.”

Pleasure? Yes, you read that right. Notwithstanding the obligatory moment of extra-aesthetic harrumphing — the introductory wall text goes on about “power imbalances and exploitation” — The Clamor of Ornament is unapologetic in its emphasis on visual effusion and stylistic fecundity. The curators have assembled an impressive array of media: mostly drawings, textiles and prints, but also photographs, books and even a set of baseball caps originally hawked to pedestrians on nearby Canal Street. A set piece juxtaposing Martin Sharp’s psychedelic homage to Bob Dylan with “The Second Knot, Interlaced Roundel with an Amazon Shield in its Center” (c. 1521), Albrecht Dürer’s woodblock riff on a design originating with Leonardo, sets the stage for a free-for-all of no little resplendence.

Among the primary virtues of The Clamor of Ornament is how thoroughly it confirms the universality of the decorative impulse. Culture and chronology are given the heave-ho for an installation that favors commonalities of rhythm and color, intricacy and generosity of pictorial spirit. “Flowers of Edo: Five Young Men”(1864), a quintet of kaleidoscopic woodblock prints by Toyohara Kunichika, is seen near a tattoo pattern book by an unknown hand from the turn of the last century. Nearby is a 1953 study for eleven ornamental bands done by John deCesare, a work commissioned by that Medici of the supermarket, General Foods. What with its abrupt shifts of locus and intent, the show might sound like a bumpy ride. In fact, it flows like a river.

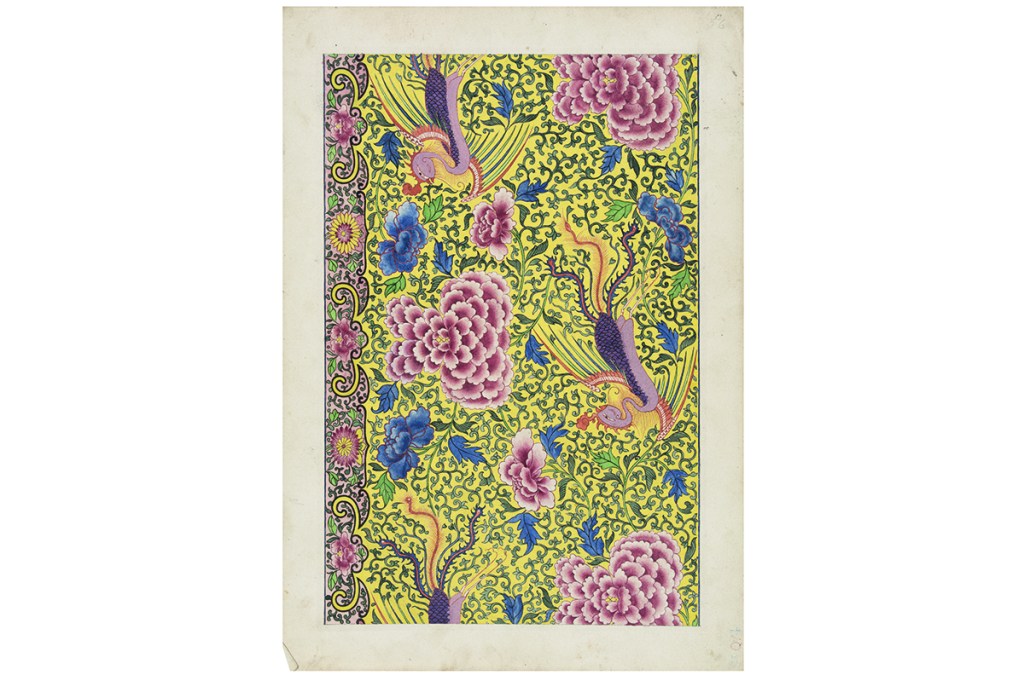

Which is appropriate, given that a majority of the work is devoted to artworks based, one way or another, on the natural world. Geometry is touched upon, particularly as an organizing principle, and symmetry is a constant. But it’s the sinuousness of organic forms, augmented by extravagant color, that predominates. Hirase Yoichirō’s sketchbook studies of seashells make the point clear, as does an unfinished watercolor, a blueprint for chrysanthemum wallpaper, by the estimable William Morris. The Welsh architect Owen Jones — whose seminal text, The Grammar of Ornament, serves as the exhibition’s lodestone — is seen to stunning chromatic effect in a trio of pieces elaborating on Chinese precedent.

Other notables include Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Louis H. Sullivan and Paul Klee. But star power doesn’t carry The Clamor of Ornament, not with showstopping pieces done by craftsmen who are unknown, anonymous or the purview of specialists. The craft, as you might imagine, is of a high order, and the work on display is, on the whole, put into shape with meticulous and sometimes mind-boggling virtuosity. Should you need a reminder of just how capable the human hand can be, particularly in our age of digital flimflammery, a visit to The Drawing Center is in order. But be warned: once the exhibition has been entered, you won’t want to leave. Splendor is addictive.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.