All the way across the Atlantic, the British literary world has been seized by John Donne fever. Katherine Rundell’s biography of the metaphysical priest-poet has led to excitable chattering about his life and work. The book, Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, will be released in the US in September — a significant enough delay as to make the Declaration of Independence look like a mistake.

Aside from radically different publication dates (again: would you rather have lower taxes and freedom from George III, or a brilliant Donne biography?), the specter of the far-off American continent has long since loomed large in Donne studies.

Academics are admittedly not famed for their tendency to see poetry, punctuation, and metaphors in the way us mere mortals — or dull sublunary types — might. But even by their standards, the debate over Donne’s elegy “To his Mistress Going To Bed” has reached absurdly over-fraught levels.

The poem in question is spoken by a man begging, cajoling, and enticing his lover to undress and get into bed with him. Donne’s speaker does not beat around the bush: “off with that girdle,” “unpin that spangled breastplate,” and “unlace yourself,” he tells his lover, before ending with the declaration that “bodies must uncloth’d be, / To taste whole joys.” There is no question what it is the speaker wants to do when uncloth’d — and it definitely isn’t reading poetry and drinking tea.

Indeed, the speaker’s priapic insistence has led some scholars to take umbrage with the poem. John Carey, the British literary critic who wrote the famous 1981 biography John Donne: Life, Mind and Art, does not mince words: “the despotic lover” orders his “submissive girl-victim to strip” while “drawing attention to his massive erection.” Carey denounces it casually as little more than “a punitive poem.”

Whip me, Professor Carey, for I can only disagree. Not only does the speaker’s erection — and nudity (“To teach thee, I am naked first”) — make the poem drolly comic, but it is also stirringly sexy, a dedication to a much-desired mistress rather than domination over a victim. The woman is a richly dressed aristocrat and a heavenly angel; she is praised, not abused.

But the stanza that has made both Donne scholars and readers stand up in alarm comes towards the end of the elegy, when transatlantic Donne relations become relevant once again:

Licence my roving hands, and let them go,

Before, behind, between, above, below.

O my America! my new-found land,

My kingdom, safeliest when one man mann’d,

My Mine of precious stones, My Empirie

How blest am I in this discovering thee!

To modern readers, this overt metaphor of a woman’s body as being a “virgin land” — both fit to be plundered and “mine[d]” for precious stones — cannot be read without wincing. This erotic delight in imperialism is the antithesis of everything post-colonial studies have taught us. How shocking, we must virtuously say, tut-tutting and shaking our heads.

For Donne shows no shame at this imperial context. By the time he was writing this elegy — between 1593 and 1596 — Elizabeth I had granted a charter to Humphrey Gilbert which “licenced his roving hands” to explore Newfoundland, Canada, and a similar charter to Sir Walter Raleigh to explore Virginia.

Donne even tried to become secretary of the newly formed trading (and colonizing) Virginia Company in 1609, and went on to preach their annual sermon in 1622. The sermon — given in the wake of the awful Jamestown massacre in March 1622 — is a plea for “Catechisme” to be thought as worthy in the Company’s American missions “as a Bugle, as a knife, as a hatchet.” By today’s standards, it is undeniably imperialistic, but by the standards of the seventeenth century, it fit a more widespread belief in the efficacy of missionary work.

America, “new-found land[s],” and colonization were political realities rather than just abstract metaphors in Donne’s time. But his roving hands continually reached for images of imperialism in his poetry. In “The Good Morrow,” his speaker calls for others to explore the “new worlds” as he has the “one world” of his lover in his bed, while in “The Sunne Rising,” his mistress becomes “the’India’s of spice.”

Are these images of sexual desire wrong, then? No longer fit to be read in the twenty-first century? An awful hangover of imperialism, and a horrible metaphor for unbridled, damaging and rapacious lust?

Some scholars have thought so — Carey sighs that Donne writes with “an almost pathological imperiousness” — while others have relied upon Donne’s status as a “coterie poet” (his work was only circulated in manuscript prior to his death) to argue that Donne was playing with — and, they suggest hopefully, undermining — expectations of colonialism and commerce.

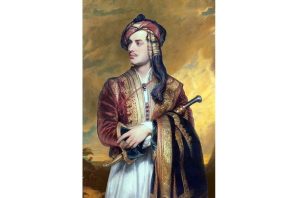

But let us forget about politics — both Donne’s and our own — and look at the poetry. “Licence my roving hands, and let them go, / Before, behind, between, above, below.” If a young, dashing poet said that to you, with his dramatic, brilliant clothes momentarily cast aside and on the floor, it would surely be impossible to resist. He is all-conquering, in all senses.

Donne excels in making things that really shouldn’t be sexy undeniably so. One of his Holy Sonnets — supposedly dating from the period of Donne’s conversion to Anglicanism from Catholicism — describes Christ’s church as “embraced and open to most men,” while another implores the “three-person’d God” to “ravish” the speaker. This is edgy, dangerous stuff. Donne’s deity is not an old man with a white beard, but an active, dominant presence, who seeks to ravish those who believe in him. Just like the poet.

Many of Donne’s images — from his sensual, sexual Church, to his rampant use of colonial metaphors — may be uncomfortable to modern readers. But they are also brilliant moments of alchemy in which almost anything can happen. Political realities are mocked and undermined as sexual possibilities, and sober, serious churches become ardent lovers. So batter my heart, many-person’d John Donne: it is time to embrace your complexities and difficulties, not to put them behind us.