The Young H.G. Wells is a biography that takes biology seriously. This is partly because H.G. Wells was a biologist before he became a writer of science fiction (his first publication was A Text Book on Biology, which he illustrated himself), but also because Claire Tomalin is alert to the life of the body as well as the mind. In her hands, Wells’s youth was less about his rise from the lower classes to become the wealthy socialist who predicted the airplane, the tank and the atomic bomb than about the rise of his weight. There is never a point in these pages when we are not told what numbers Wells saw when he stood on the bathroom scales, or reminded of the connection between his physical evolution and his evolution as a writer.

Herbert Wells was born in Bromley, England in 1866, beneath the shop where his father, Joe, sold crockery and cricket bats. His mother, Sarah, was 44, and Bertie would be her last child. In his earliest memories of her she has already lost several teeth and her hands are gnarled by years of sewing, mending and cleaning. Bodies, in the Wells family, were forever falling apart, something Bertie turned to his advantage. When, aged seven, he broke a shin bone, his convalescence became a period of uninterrupted reading. Not only did he emerge from his bedroom with a planet-sized brain but he had also discovered his legendary libido, stirred into life when he saw illustrations of a semi-clad Britannia and pillowed his head against her naked bosom. His own naked body, we are told, smelt of honey.

Four years later there was another lucky accident when Joe fell off a ladder and broke his thigh bone, which made him no longer able to work in the shop. To feed her family (Bertie almost certainly suffered from malnutrition), Sarah took up the position of housekeeper at Uppark, a 17th-century Dutch-style mansion set high in the South Downs, where she had formerly been employed as a lady’s maid. Her youngest son, who was given a bedroom in the servants’ quarters, would later refer to the house as home, but his feelings towards Uppark were ambivalent. On the one hand he loved the landscape, the books, the gardens and Christmas parties; on the other, he loathed the inequality it represented.

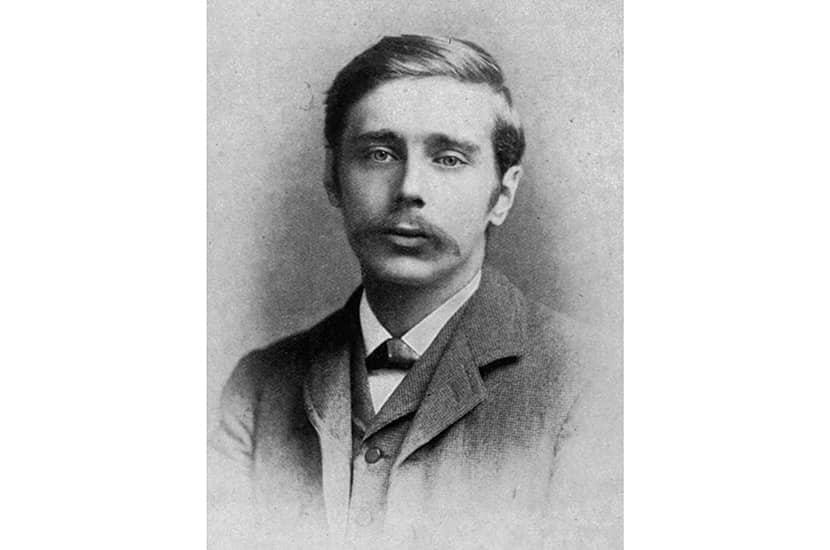

Leaving school at 14, he trained first as a draper and then as a teacher until, aged 18, he won a studentship to study biology under Professor Thomas Huxley at the Normal School of Science on Exhibition Road (where the Science Museum is today). His weight, Tomalin tells us, was “little more than seven stone [98 lbs], his ribs showed, he had not much muscle, and he felt himself to be a poor specimen.” Under Huxley’s tutelage, his mind became saturated with the scientific ideas which he would apply in his fiction to the problems of his age.

At 20 — and still under 115 pounds — he crushed his kidney and smashed his pelvis during a rugby game. At 23, he reached his final height of 5ft 7in. By the following year, when he achieved a first-class honors in zoology and was elected Fellow of the Zoological Society, he weighed 117 pounds. He now had an attack of influenza, which led to the congestion of the right lung. His condition was such that he returned to Uppark, where he was provided with an excellent doctor to monitor his recovery and a bevy of maids to fuss over him. In other words, the social inequality of Uppark saved his life.

Given his wretched health, writing seemed like a sensible occupation. “I think the groove I shall drop into will be cheap novelette-eering,” he decided, but everything he sent to magazines was rejected. “Some day I shall succeed, I really believe,” he told himself, “but it is a weary game.” Meanwhile he penned quiz questions for papers such as Tit-Bits, and soon learned that by submitting the right answers he could win the prize money as well.

Aside from his lack of fame, the most urgent problem of his life so far was his virginity. The solution lay, he believed, with his cousin Isabel. He proposed to her when he was 20 and they married when he was 26 (his weight now fell to 112 pounds). Marriage was not, however, an institution he believed in. It was “perfectly disgusting to me,” he said, how “two people, after half a dozen weeks’ intercourse will bind themselves to burden and bore each other for the rest of their days.”

Having been a faithful fiancé, his infidelities began at once. He plowed through each affair with no concern for the carnage caused; a life of “enterprising promiscuity,” as he called it, was one of his rights as a man. Tomalin describes the Wells marriage as:

“a miserable fiasco [in which] a reluctant young woman, embarrassed and afraid, succumbed to an uncontrollably ardent husband who gave her no pleasure but forced himself into her, reducing her to wretchedness and tears.”

The next year Wells again hemorrhaged from the lung and nearly died. Convalescing in Eastbourne he wrote an article called “On the Art of Staying at the Seaside,” which was accepted by the Pall Mall Gazette, which then printed his next 16 submissions. Against all odds, H.G. Wells was launched: “In a couple of months, I was earning more money than I had ever done in my class-teaching days. It was absurd.”

The hemorrhages continued into his thirties, by which point Isabel had been displaced by the long-suffering Amy Robbins, whom Wells for some reason rechristened Jane. She shared his views about marriage and social equality and they embarked together on a “working life.” This meant that while Wells wrote The Time Machine and became known as a man of genius, Jane, the invisible woman, took on the time-honored role of secretary, gave birth to his first two sons, and stood by while he carried on his affairs — as Tomalin puts it, “in blazes of publicity.” Among the women who smelt his honeyed skin were the novelists Dorothy Richardson, Violet Hunt and Elizabeth von Arnim.

One of the many revelations of this elegant study of a man in a hurry is that Wells’s literary reviews were as prescient as his other prophecies. He saw at once, for example, that Jude the Obscure was “a book that alone will make 1895 a memorable year in the history of literature.”

Tomalin, now in her late eighties, ends her biography when Wells is in his forties and getting chubby. He has published The History of Mr Polly, about a man who breaks free from his marriage, and his latest girlfriend, Amber Reeve, the model for Ann Veronica, is pregnant with their daughter. He has not yet impregnated Rebecca West or started addressing Jane as “Mummy,” but now that the pattern of his life is set, his own future, we might say, is predictable.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.