Who would you choose to judge you long after your death? How about a professional historian? How about Felipe Fernández-Armesto? Much lauded and read, this professor of history at the University of Notre Dame is the author of many books including short histories of humankind and the world and longer ones of exploration, Hispanic America and the year 1492. As you begin Straits, his account of the life and voyages of Fernando de Magallanes, known in English as Ferdinand Magellan, the explorer credited with the first European navigation from the Atlantic to the Pacific via the straits at the tip of South America in 1520, you may quail at the thought of his searing judgment. He can be waspish, uncompromising and cutting. Explorers were liars, seafarers are generally irresponsible and today’s graduates “find modesty an encumbrance and accuracy a superfluity.” Our judge has an entertainingly low regard for common opinion, swiping at the “vulgar errors” of less-acute historians, and is scarcely modest about his own expertise: “I undertake the closest reading ever of the texts that are available… I can show more of what Magellan was like than any of my predecessors.”

What follows is rigorous, deft and entertaining history, though I did feel anxious on Magellan’s behalf as this investigation into his character and conduct proceeded. I’ve done a bit of exploring myself, I thought — and may be judged by someone like Felipe Fernández-Armesto. The book depicts the world Magellan knew, which most of us do not at all. If you thought the age of exploration saw sophisticated Europeans barging their way to the discovery and domination of less sophisticated lands, you are guilty of vulgar errors. In fact, travelers from the cold and comparatively barren north came from “a relatively poor backwater, despised as barbaric in the richer societies that lined the shore of maritime Asia.” The most dynamic societies of the fifteenth century were to be found in the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa, Fernández-Armesto explains:

Indeed, in terms of territorial expansion and military effectiveness… native African and American empires outclassed any state in western Europe until the establishment of the global Spanish monarchy in the sixteenth century.

Crudely put, the difference was going to be ships. When it was discovered that the Indian Ocean was not landlocked (the book is excellent on the way prevailing winds and ocean currents determined the shape of the world as it was known to Europeans) and awash with valuable commodities including spices and gold, any European who could get a trading ship there and back was going to be rich.

In his twenties, Magellan learned to sail, fight and do business in the service of his native Portugal along the Malabar coast of India, on the Arabian and Laccadive seas, and in Goa, Cochin (now Kochi) and Quilon (Kollam). He was also in Malacca (Melaka) and Morocco, where he seems to have pocketed some of the proceeds of a cattle raid. Suspicions of criminality came to little, but the incident raised doubts about his integrity.

The first half of Straits is concerned with what we know about Magellan up to the moment in 1519 when, having fallen out with the Portuguese crown, he set forth in the service of Spain, leading the expedition that would cost him his life and secure his fame. It is a rich story, full of charismatic figures. Among my favorites is Ludovico Varthema, who wrote of traveling “for my pleasure and to know many things,” and who was called “a great liar” by those who knew his friends. His account of his travels in the East, published in 1510, went through twenty-seven editions in four languages and is distinguished, says Fernández-Armesto, by its author’s Flashman-like “conviction of his own sexual irresistibility.” Varthema claimed to have been the first non-Muslim to visit Mecca, from where he traveled to Aden. Discovered by its sultan to be a Christian, Varthema claims he was saved from execution by his lover, the sultan’s wife. Fernández-Armesto discerns “a canny sense of the book market in every lubricious scene of seduction and sexual hospitality.”

Magellan read it and seems to have trusted Varthema’s reports of a group of spice islands east of Java, inhabited by lawless, savage, stupid people. This was enticing. Explorers were surprisingly strictly briefed in good conduct towards any established society they might encounter. The instructions of Carlos I of Spain to Magellan show a concern for the moral standing of the crown and kingdom, which seems extraordinary, given events later in the Spanish conquests in the Americas. Women were to be respected, trading should be fair and no guns were to be used in new lands “because the indios fear this more than anything else.” But the savage, stupid and wild were another matter. Their lands were fair game.

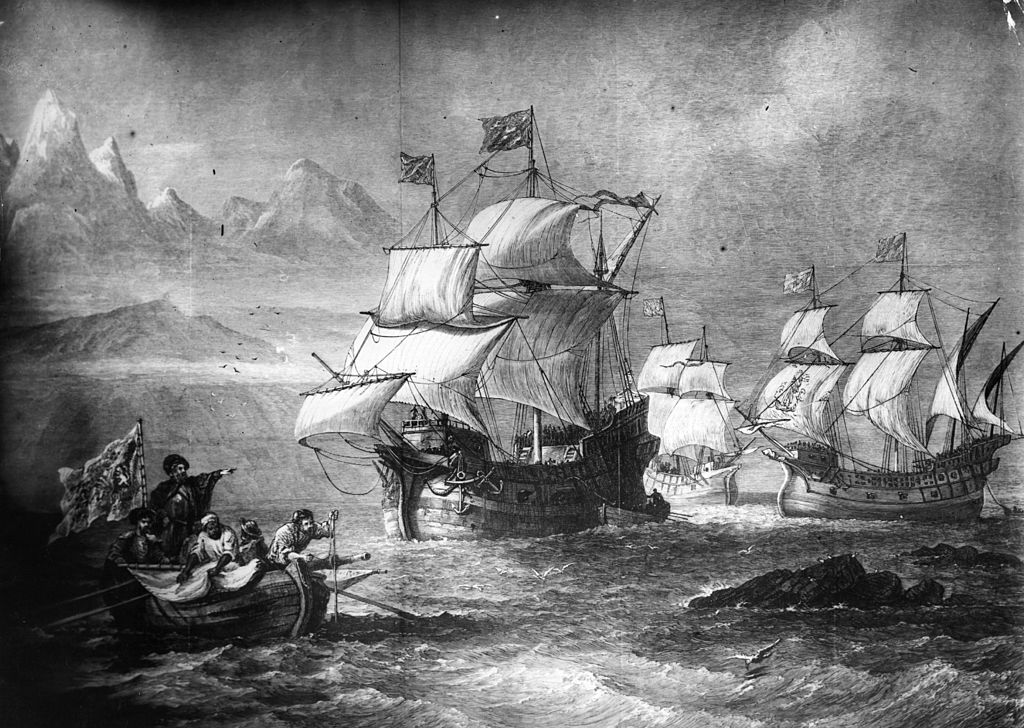

By the time Magellan’s fleet sets out, at the book’s midpoint, you are itching for action. This wildly expensive expedition was years behind schedule, already riven by rivalries and politically controversial (Spain was anxious to remain on good terms with Portugal, and no one thought Magellan, effectively a traitor to the Portuguese cause, could be relied upon in this area). Magellan confided to a friend that once at sea he intended to do exactly as he pleased. The buggery of an unfortunate cabin boy led to the expedition’s first death: Magellan had the perpetrator garroted.

Magellan had undertaken to tell the other captains the planned route but subsequently refused to do so. When they objected, he imprisoned their leader, whom he later marooned off Patagonia. No one on the voyage, and certainly not the backers or the king, had any idea that Magellan intended to search for a passage around the Americas to the far side of the world. As the fleet bore south into the cold and storms, things heated up nicely, with the execution of mutineers.

This is not history as Jan Morris wrote it. You get little sense of the places described as they are now beyond one depiction of a statue of a historian in Princeton. And I disagree with Fernández-Armesto about seafarers. They are not irresponsible: most still make horrendously long journeys to support families they almost never see. But this book is a sparkling read. The author is a fierce judge, but mostly a fair one.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.