In 1929 in America, Dashiell Hammett published his debut hardboiled novel Red Harvest, over in Paris Buñuel and Dalí began showing their film Un Chien Andalou at a small cinema, while in Britain the fledgling Decca Record Company opened for business.

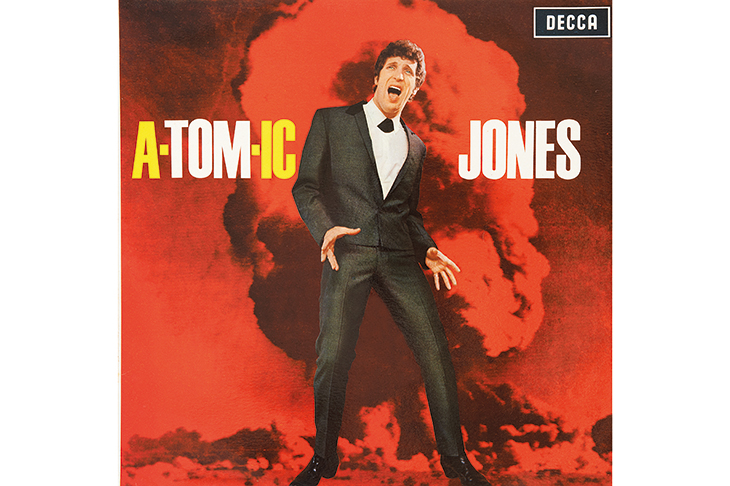

Issued to mark 90 years of the label’s existence, this large format, fully illustrated volume benefits greatly from access to its extensive archive of the days when Billie Holiday, Kathleen Ferrier, Tom Jones, Pavarotti, Bing Crosby, Buddy Holly, Herbert von Karajan, Billy Fury, Marianne Faithfull, George Formby, Slaughter & the Dogs, Georg Solti, Benny Hill, Winston Churchill and even the Playboy Club Bunnies appeared on Decca or its subsidiaries.

Decca’s history is inextricably bound up with that of its founding director, Sir Edward Lewis, who persuaded a successful gramophone manufacturer of that name to move into the record business. Shares in the new company began trading in February 1929, and that they survived the subsequent Depression and went on to establish a formidable artist roster in the 1930s was in no small part due to Lewis’s abilities and perseverance. In January 1980, weeks before his death, he sold the company to the Dutch conglomerate PolyGram, after which its historic studio in West Hampstead was closed and its pressing plant and head office building disposed of. Although the Decca name has since been retained through several corporate buyouts, some might argue that the real story ended with Sir Edward.

The editors have assembled some fine writers to contribute individual sections exploring the label’s varied output. Michael Gray provides fascinating details on the origin of Decca’s industry-leading full frequency range recording process, developed during wartime to track U-boats; while Lois Wilson is equally good at telling the story of the US Decca offshoot, which scored many hits with artists such as Louis Jordan and Bill Haley.

Jon Savage covers the glory years of 1950s and 1960s British pop in fine form, when the Rolling Stones, Them and the Who cut timeless albums for the label. It’s worth noting, however, that when discussing Joe Meek’s unique 1962 composition and production, ‘Telstar’ by The Tornados, reaching No. 1 in America, he says only two British acts had ever achieved that position before — Laurie London in 1958 and Acker Bilk in 1962. In fact, someone got there ahead of them in 1952, becoming the first foreign artist to top the Billboard charts. It was Vera Lynn, with the million-selling ‘Auf Wiederseh’n Sweetheart’, released by Decca, the label she’d been with since 1937, and for whom, aged 102, she wrote a foreword to this book.

This is a very good-looking production, a sumptuous and substantial LP-sized coffee table book, although it is questionable whether the average reader desperately needed five pictures devoted to the 1978 novelty act Father Abraham & the Smurfs. Nevertheless, the clear reproduction of large quantities of vintage press clippings preserved by the company’s publicists is very welcome. ‘Text © Decca Records’ reads the verso page, and it is certainly the story as they wish it to be told.

That said, there is much to enjoy here, always allowing for the inevitable shifts of mood between sections. Those who appreciate the very good accounts of the technical challenges of recording opera in the immediate post-war era may not want in-depth examinations of the rock and pop catalogue, and vice versa. However, perhaps the book’s main value is as a survey of the sheer range of activities of one of the key players in the industry.

Throughout the volume there is a compulsive tendency to name-drop David Bowie. Yes, Decca’s subsidiary, Deram, released various singles and his Anthony Newley-obsessed debut LP in 1967 — and swiftly dropped him when they didn’t sell — but he also recorded for Pye and Parlophone, finally scoring a hit for Phillips in 1969 before his lengthy run of classics for RCA. Despite appearing here on 14 different pages scattered across the book, his sole hit for the label was the 1973 post-Ziggy cash-in reissue of the 1967 comedy single ‘The Laughing Gnome’.

Some readers will not agree with chapters covering the 21st-century catalogue which suggest that releasing mass-market ‘classical crossover’ artists such as Katherine Jenkins and Russell Watson is somehow following in the tradition of the days when the company put out works such as Britten’s War Requiem. Dismay might also greet Adam Sweeting’s claim that Handel was ‘the Andrew Lloyd Webber of his generation’, or the current vice president Tom Lewis referring to signing Donny Osmond in 2002 as one of the label’s ‘key acts’. Indeed, the middle-of-the-road artists, classical-lite orchestras, royal wedding souvenirs and military bands of recent years may sell in impressive numbers, but as former Decca recording artist and jazz musician Spike Milligan once remarked: ‘If you’ll stand for the national anthem, you’ll stand for anything.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator‘s UK magazine.