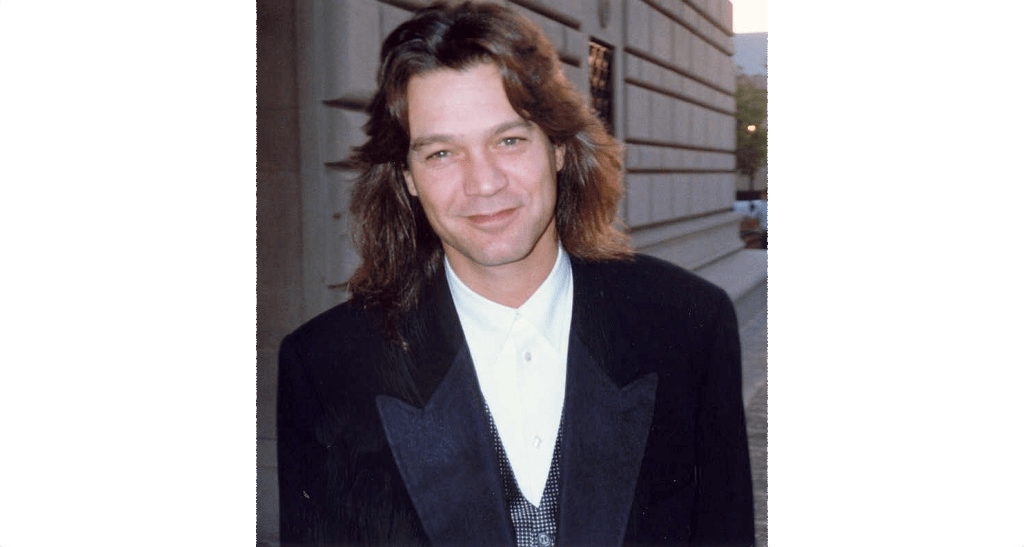

The death of legendary ax grinder Eddie Van Halen is a sad reminder of how far rock music has fallen since those heady, head-banging days of the 1970s and 1980s when hairy, denim-clad blokes bestrode the earth, power-chording their way into our collective consciousness.

Once the foundation of any self-respecting rock anthem, the obligatory guitar solo was where musicianship took flight and Eddie was a master at his craft. From speed metal to prog, album-orientated rock to epic ballads, soloing gave rock music its backbone. Unlike boring drum solos, everyone could appreciate the excitement of a well-crafted guitar break. So what happened, why did we fall out of love with one of rock’s founding principles? Could it be that modern guitarists simply aren’t up to the job or perhaps we’ve all become too coolly ironic to take this most showy of art forms seriously?

Back in the early 1970s, we had no such qualms. The likes of Jimmy Page, Richie Blackmore and Tony Iommi were lionized not only for their showmanship but for their extraordinary versatility and musical proficiency. These rock god perfectionists were inspired by the great blues artists of the 1950s and 1960s such as B.B. King and Muddy Waters as well as classical adventurers like Sibelius and Mahler. It was Jimmy Hendrix of course who took the classic 12-bar progression and turned it into something altogether sexier.

Soloing came in all sorts of shapes and sizes from the fiendishly fast lyrical harmonics of Eddie Van Halen to the searing melancholia of Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour. Classically inclined prog guitarists like Yes’s Steve Howe took the electric guitar into new and uncharted territory. Keen to distance himself from the standard blues template of his contemporaries, Howe added plucky jazz fusion and country-style noodlings to classically inspired 20-minute Yes opuses. Meanwhile, power chord maestros such as Brian May and Pete Townsend kept their freak flags flying with phallic poses and wildly flailing arms.

Solos tended to appear halfway through a track either to mark an emotional high point or as a way of transitioning into a modulated second act. Sometimes they were incorporated into extended outros that left fans breathless for more. Listen to the extended eight-minute live version of ‘I’m So Afraid’ by Fleetwood Mac and marvel at the way Lindsey Buckingham builds tension with bluesy guitar swoops that gradually shift into a crescendo of thundering, orgasmic fret-runs. Occasionally a track will launch straight into a massive power riff to remind the listener that the band means business — think Deep Purple’s ‘Smoke on the Water’, Led Zeppelin’s ‘Whole Lotta Love’ and Eddie Van Halen’s spluttering intro to ‘Ain’t Talkin’ Bout Love’.

By the mid-1970s, record labels had grown tired of indulging the whims of extravagant ax men and were now looking for more cost-effective ways to sell rock music that didn’t involve lorry loads of expensive Stratocaster guitars. Some argue that punk’s pared-down vibe owed more to corporate expediency than youthful rebelliousness; why waste time and money nurturing talent when a lack of talent could be sold as a virtue. Keen to distance themselves from the old guard, the new scallywags of punk baulked at the idea of exhibiting skill and dexterity via a 30-second solo, opting instead for discordant shredding that sounded like an ‘up yours’ to the previous generation’s love of craftsmanship.

In the UK, punk’s meteor wiped out a whole generation of talented guitar rockers while over in the US, bands like Van Halen were only just getting started — the group’s first album came out in February 1978 just as punk’s light was beginning to fade.

[special_offer]

By the early 1980s, many of the monsters of British metal were back, joined by hairy young pretenders like Iron Maiden, Saxon and Def Leppard. Older bands, once seen as past their prime, were given a glossy, 1980s makeover. Stylists turned lank locks into poodle perms while tinny drum machines replaced old-fashioned tom-toms and synthesizers took the place of Hammond organs. This being the 1980s, guitar solos also took a turn for the brash, becoming more aggressive and a good deal less satisfying. Despite the corporatization of rock, some of the older guitar heroes managed to retain their dignity — Eddie Van Halen’s frenetic fret-work on classics such as ‘Jump’ and Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It’ came to define the joy and optimism of what would soon become a nostalgic memory. By the late 1980s, the writing was on the wall as cartoony ‘hair bands’ such as Motley Crue and Poison turned soloing into a coarsened parody. Po-faced grunge delivered the final blow as introspective naval gazers turned to nihilistic amp distortions and atonal strumming to attract a new generation of miserablists.

Even so-called ‘guitar bands’ of the 1990s shied away from soaring solos and mighty riffs, preferring the plaintive, repetitive strum that has continued to underscore so much modern rock music.

The mainstream may have abandoned one of its core attractions but solo lovers need not despair. YouTube is awash with fledgeling ax grinders honing their craft by playing along to the classics. If only record label execs had the courage to nurture all that wasted talent so that future generations might be able to mourn the passing of their very own Eddie Van Halens.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.