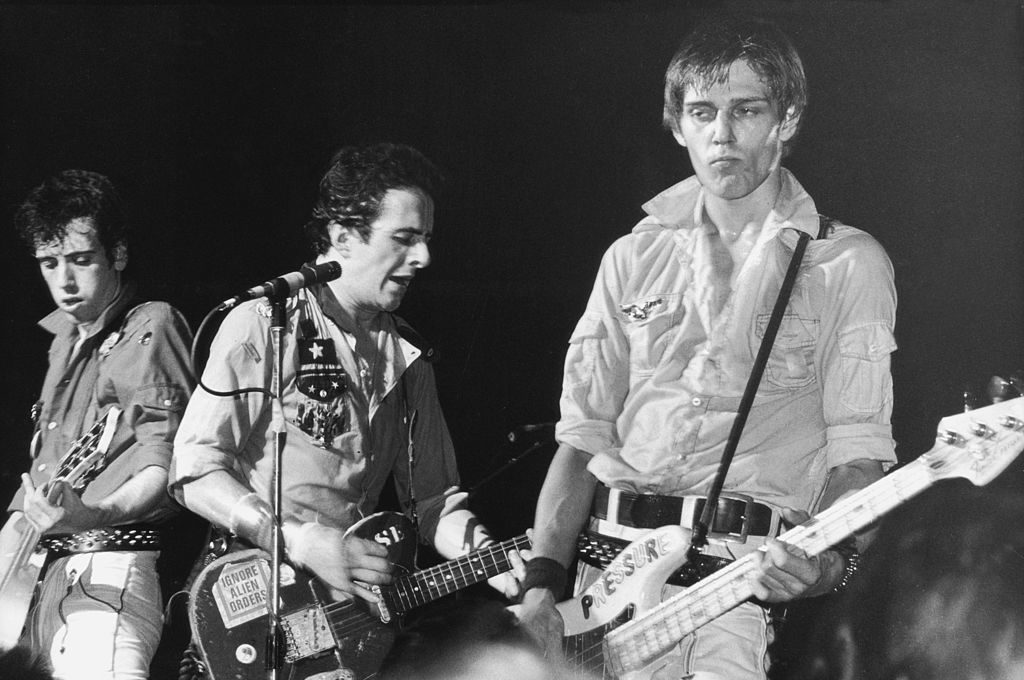

Boris Johnson recently cited the Clash as his ‘favorite band’ along with the Rolling Stones. London Calling, the Clash’s great third album, was released in the US in January 1980, 40 years ago next month. Time has judged it one of the great rock ‘n’ roll albums, but was it really made for Establishment figures like the British prime minister?

For the affordable price of $7.98 the 19-tune, double LP hit the New Year market in a blaze of righteous Jamaican reggae and driving, dance-floor ska, 12-bar jazz, mento-calypso, disco, funk and much else besides. Having just returned from an American tour on which they were supported by the blues showmen Bo Diddley and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, the Clash were fired up with the romance of America.

Appropriately, the album’s cover replicated the luminous pink-and-green lettering of Elvis Presley’s first album sleeve — one of America’s most revered debuts. If the Clash had discovered America (and by extension, themselves), not everyone was happy. Punks who had endorsed the band’s ‘no Elvis, Beatles or the Rolling Stones’ line from the B-side of their 1977 single ‘White Riot’ were put out. From their amphetamine-spiked early days as a London garage combo who professed to be ‘bored with the USA’, the Clash had assembled a wildly disparate collection of songs that juxtaposed musical styles from far and wide.

The album’s 65 minutes dig deep into Depression-era railroad folk, rockabilly and even Tin Pan Alley show-tune harmony (the skiffle-like swing of ‘Jimmy Jazz’, the melancholy of ‘Train in Vain’). The songs tell of the death of an opium den gambler ‘seized and forced to his knees and shot dead’ (‘The Card Cheat’) and the druggy self-destruction of the Hollywood matinee idol Montgomery Clift (‘The Right Profile’). In ‘Brand New Cadillac’ — a cover of a 1950s song by Vince Taylor — we listen to a young woman Cadillac owner berate her Daddy (‘I ain’t never coming back’). The album has the density and variety of a film, and the band knew it. The LP was sold in the UK with a sticker which proclaimed the Clash as ‘the only band that matters’.

The wonder is that it ever got finished. The band’s chaotic producer, Guy Stevens, caused all manner of problems in the recording studio, from blowing up the mixing desk, smashing chairs in front of CBS record executives (while the band recorded ‘Death or Glory’), fighting drunkenly with his engineer, nodding out under the console and at one point pouring red wine into the piano because, he told Clash guitarist Mick Jones, it would ‘sound better’. Having produced Mott the Hoople, Free and other mid-1970s British rock acts, Stevens added saxophone, barrelhouse piano and multiple drum signatures to the Clash’s habitual power chord workouts and riffs borrowed from Dr John’s New Orleans R & B and the pub rock blues of British bands like Dr Feelgood. The result had the stridency, swagger and passion of punk-era Clash but was more expansive and mellow in atmosphere. (Wretchedly, Stevens died of an overdose at the age of 38 just two years after London Calling was released.)

A harbinger of change for the Clash, London Calling appeared seven months after Margaret Thatcher’s election triumph in May 1979: a watershed moment for the world that saw a free-market evangelist installed in Number 10. With its escapism into Americana and the music-hall rock of the Kinks (the descending bassline of ‘I’m Not Down’ recalls that of ‘Waterloo Sunset’), London Calling served as a tonic to the grim reality of a late-1970s Britain in which the Labour government under Jim Callaghan appeared bankrupt and played out.

In these unstable times, Strummer did not want an action replay of the Clash’s eponymous 1977 debut album: a virtual snapshot of blue-collar British youth beaten down by mass unemployment and public sector walkouts. London Calling, with its array of backing vocals, overdubs and casual ad-libs (‘start all over again!’, ‘It’s ridiculous, innit?’, ‘What a relief!’), found the Clash in a less combative, but still political mood.

The adrenalin-quickening title track offered a dystopian, sci-fi vision of London preyed on by underworld zombies following a ‘nuclear error’ (ironically, global cooling, not warming, was then the terror). It could be a front-line report from the UK’s 1978 ‘Winter of Discontent’, when rubbish was left to pile 20 feet high in London’s Leicester Square and bodies accumulated in hospital morgues after gravediggers went on strike.

Triumphantly, London Calling builds on the band’s long-standing love of Jamaican music. It is steeped in the bass-heavy, trance-inducing vibes of Afrocentric 1970s reggae albums such as Satta Massagana by the Abyssinians and Culture’s Two Sevens Clash. A cover of Junior Murvin’s 1977 reggae hit ‘Police and Thieves’ had appeared on the Clash’s first album, and the gruff-voiced Jamaican deejay-singer Prince Far I was name-checked on their 1978 single ‘Clash City Rockers’.

London Calling’s standout reggae track, ‘Guns of Brixton’, written by the band’s bassist Paul Simonon, alludes to Jamaican outlaw Vincent ‘Ivan’ Martin, who terrified the Jamaican capital of Kingston in the 1940s with his armed hold-ups until a police manhunt left him dead. To Simenon’s romantic imagination, ‘Ivan’ was a Caribbean Ned Kelly figure who eluded capture even as he taunted the authorities.

The album’s outlaw imagery of guns and gang warfare was naïve romanticism. In 1977, Strummer had accompanied Mick Jones to Kingston, only to find the city on the edge of bloodshed. (‘I went to the place where every white face is an invitation to robbery,’ Strummer sang on ‘Safe European Home’, an oblique comment on Jamaica.) The album’s badland balladry sat well with punk’s vaunted anti-establishment credentials. ‘Wrong ‘Em Boyo’, a ska jolly-up sired out of an old New Orleans tune, tells of the 19th-century African American folk hero Stagger Lee, who shot dead a white man; ‘Revolution Rock’, the 11th song, draws on Perry Henzell’s cult Jamaican film The Harder They Come (1972), which depicts the bullet-scarred life of an Ivan-like outlaw as he struggles to survive in the ganja-yards and urban alleys of western Kingston.

On the album’s cover was Pennie Smith’s now-famous photograph of Simonon smashing his bass guitar on to the New York Palladium stage. Out of focus, the shot suited the band’s ragamuffin image and moreover recalled the Who’s auto-destructive stage antics. Though the Ramones had released a double live album of punky, three-chord anthems in 1977, the idea of a double album was essentially alien to punk’s DIY ethos of self-motivation and singles-only output. While some British critics objected to London Calling’s alleged commercialism — one reviewer punned on the title of the band’s previous album, Give ’Em Enough Rope, by titling his negative opinion ‘Give ’Em Enough Dope’— American critics applauded the music’s immense breadth and what the New York Times called its ‘primal energy’.

London Calling sold two million copies overnight and propelled the Clash all guns blazing into the 1980s. Their sequel, Sandinista!, a sprawling triple album, offered much more reggae and even rap (‘The Magnificent Seven’), as well as Jamaican deejay-styles of delivery, dubbing and ‘toasting’. But for all Sandinista!’s hymnal, incantatory qualities, the Clash had, it seemed, run out of puff. Joe Strummer fired first their heroin-addicted drummer Topper Headon and then his songwriting partner Mick Jones, and the band was over.

Strummer, who died in 2002 at the age of 50 of an undiagnosed congenital heart defect, was very much in favor of fighting Islamism after 9/11 ‘The evil brilliance is just too much,’ he told the Philadelphia Inquirer a week after the attack, adding, ‘I can’t get away from those images when I go to bed at night.’ He may not have cared for Boris Johnson’s comparison of burka-wearing Muslim women to ‘letterboxes’. He certainly would not have cared for the Conservatives’ latest campaign video.

In the video, Johnson strolls breezily round the Tory party headquarters in man-of-the-people mode (‘How are you? Nice to see you’), before facing the question no politician should ever be asked. And should never answer:

‘What’s your favorite band?’

Strummer, oddly true to his own son-of-a-diplomat, boarding-school upbringing, was at heart a contrarian and non-conformist. Perhaps Boris sees in him a strain of London bolshiness, or the faux working-class Toryism that distinguished, say, the Kinks in their nostalgia for the village green and England’s ‘old ways’. Johnson’s predecessor, the Eton-educated David Cameron, has expressed a love of the class-war anthem ‘Eton Rifles’ by that very English band the Jam. In 2007, no less awkwardly, British Conservatives adopted Jimmy Cliff’s ‘The Harder They Come’ as a Tory anthem. The party of law and order thus endorsed, if unwittingly, the crime habits of a Kingston rude boy. Still, Johnson got one thing right: The Clash, the last great British rock band, were like nothing before or since.